Distributed Systems -- Reliability Issues -- Module 4

Index

Types of Failures

Types of Failures in DDBSs

In a distributed database system, failures are more complex than in centralized systems because of the distributed nature of the architecture. Multiple sites, networks, and transactions interacting across locations increase the likelihood of something going wrong. Here are the main types of failures you’ll encounter:

-

Site Failure:

- This occurs when a single node (or site) in the distributed system crashes.

- Causes: Hardware issues (e.g., server failure), software bugs, or power outages.

- Impact: The site becomes unavailable, but other sites may still function, leading to a partial system failure.

- Example: If a site in Mumbai hosting a fragment of a customer database crashes, that fragment becomes inaccessible, but sites in Delhi or Bangalore might still be operational.

-

Network Failure:

- This happens when the communication links between sites fail, often resulting in a network partition.

- Causes: Physical link failures (e.g., cable cuts), network congestion, or router issues.

- Impact: Sites can’t communicate with each other, which can isolate parts of the system and lead to inconsistencies.

- Example: If the network link between two sites fails during a transaction, one site might commit while the other aborts, causing inconsistency.

-

Transaction Failure:

- A transaction fails to complete due to internal issues.

- Causes: Logical errors (e.g., invalid user input like dividing by zero), system-detected issues (e.g., deadlock), or timeouts.

- Impact: The transaction is aborted, and the system must roll back any changes to maintain consistency.

- Example: A transaction updating a bank account balance fails because of a deadlock with another transaction, forcing a rollback.

-

Media Failure:

- This involves the loss of data on storage devices.

- Causes: Hardware failures like disk crashes or corruption.

- Impact: Data stored on the affected device becomes unavailable, potentially leading to data loss if not backed up.

- Example: A disk storing a fragment of a sales database fails, making that fragment inaccessible until recovery mechanisms (like backups) are used.

Key Considerations

-

Partial vs. Total Failure: In DDBSs, failures are often partial (e.g., one site fails while others remain operational), unlike centralized systems where a failure typically brings down the entire system.

-

Detection: Failures are detected using mechanisms like timeouts or heartbeat messages (e.g., a site not responding within a set time indicates a failure).

-

Impact on Reliability: These failures challenge the system’s ability to maintain data consistency, availability, and atomicity, which is why reliability techniques (the next topic) are crucial.

Reliability Techniques

Reliability Techniques in DDBSs

Reliability techniques in distributed database systems are designed to handle the failures we discussed (site, network, transaction, and media failures) and ensure the system remains consistent, available, and fault-tolerant. Here’s a breakdown of the key techniques:

https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/recovery-in-distributed-systems/

-

Redundancy:

- What It Is: Storing multiple copies of data across different sites to ensure availability if one site fails.

- How It Works: Data replication ensures that if one site goes down, another site with a copy of the data can take over.

- Example: A customer database fragment in Mumbai is replicated in Delhi. If the Mumbai site crashes, the Delhi site can still serve the data.

- Trade-Off: Increases storage costs and requires mechanisms to keep replicas consistent (e.g., using synchronization protocols).

-

Logging:

-

What It Is: Recording transaction operations in a log file to track changes and enable recovery after a failure.

-

How It Works: Logs store “before” and “after” states of data changes. If a failure occurs, the system uses the log to undo (rollback) or redo (reapply) transactions.

-

Example: Write-ahead logging ensures that a transaction’s changes are logged to disk before being applied to the database, so a site failure doesn’t result in lost updates.

-

Benefit: Essential for maintaining atomicity and durability in transactions.

(Covered in DBMS organizer notes pdf at the end.)

-

-

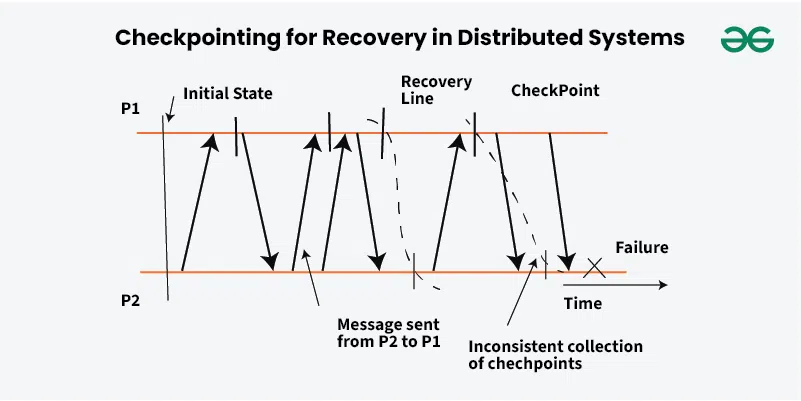

Checkpointing:

-

What It Is: Periodically saving the system’s state to reduce the amount of work needed during recovery.

-

How It Works: The system takes a “snapshot” of its current state (e.g., active transactions, data in memory) and writes it to stable storage. After a failure, recovery starts from the last checkpoint instead of the beginning.

-

Example: A DDBS checkpoints every 10 minutes. If a failure occurs at 11:40 AM, recovery begins from the 11:30 AM checkpoint, minimizing data reprocessing.

-

Benefit: Speeds up recovery but introduces overhead during normal operation.

(Covered in DBMS organizer notes pdf at the end.)

-

-

Failure Detection and Recovery:

- What It Is: Mechanisms to identify failures and initiate recovery processes.

- How It Works:

- Detection: Uses techniques like heartbeat messages (periodic signals between sites to confirm they’re operational) or timeouts (if a site doesn’t respond within a set time, it’s assumed to have failed).

- Recovery: After detecting a failure, the system reassigns tasks to operational sites, rolls back incomplete transactions, and uses logs to restore consistency.

- Example: If a site stops sending heartbeat messages, the system marks it as failed, reroutes queries to another site, and uses logs to recover any in-progress transactions.

- Benefit: Ensures the system can continue functioning despite partial failures.

Key Considerations

-

Balancing Overhead and Reliability: Techniques like redundancy and logging improve reliability but add overhead (e.g., increased storage, processing time). The system must balance these trade-offs.

-

Distributed Nature: In DDBSs, reliability techniques must coordinate across multiple sites, which adds complexity compared to centralized systems. For example, ensuring all replicas are consistent after a failure requires synchronization.

-

Relation to Failures:

- Redundancy helps with site and media failures by providing backup data.

- Logging and checkpointing are crucial for transaction and site failures to recover the system state.

- Failure detection mitigates network failures by identifying isolated sites.

Commit Protocols

Commit Protocols in DDBSs

Commit protocols ensure that distributed transactions maintain atomicity—either all sites commit the transaction, or all abort it, even in the presence of failures. This is critical in DDBSs because transactions span multiple sites, and a failure at one site shouldn’t leave the system in an inconsistent state. Let’s break down the key commit protocols:

https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/two-phase-commit-protocol-distributed-transaction-management/ (2PC)

-

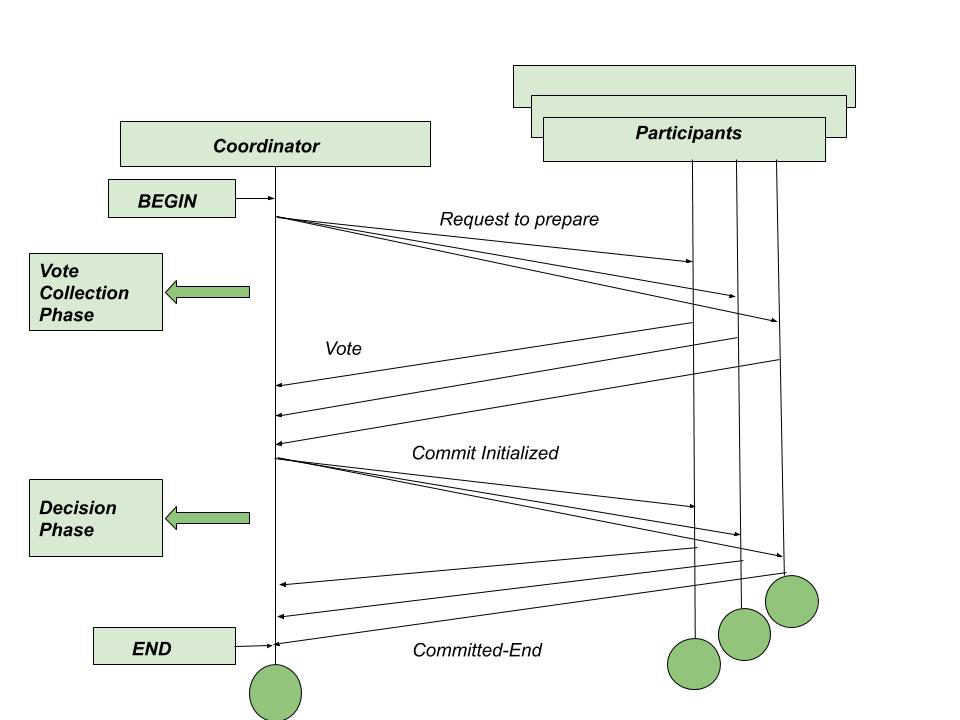

Two-Phase Commit (2PC):

-

What It Is: The most widely used protocol to ensure atomicity in distributed transactions.

-

How It Works: 2PC operates in two phases, coordinated by a central node (called the coordinator):

-

Phase 1 (Prepare Phase):

- The coordinator sends a “prepare” message to all participating sites.

- Each site performs the transaction locally (up to the point of committing) and responds with a vote: “yes” (ready to commit) or “no” (cannot commit, e.g., due to a local failure).

- The site also writes its vote to a log for recovery purposes.

-

Phase 2 (Commit/Abort Phase):

- If all sites vote “yes,” the coordinator sends a “commit” message, and each site commits the transaction.

- If any site votes “no” (or fails to respond), the coordinator sends an “abort” message, and all sites roll back the transaction.

- Sites log the final decision (commit or abort) to ensure recovery after a failure.

-

-

Example: A transaction updates a bank account balance across two sites (Mumbai and Delhi). The coordinator sends a prepare message. Both sites vote “yes,” so the coordinator sends a commit message, and both sites update the balance. If Delhi had voted “no,” both sites would abort.

-

Pros: Guarantees atomicity across all sites, ensuring consistency.

-

Cons:

- Blocking Issue: If the coordinator fails after the prepare phase, sites are stuck waiting for the final decision (they can’t commit or abort on their own).

- Single Point of Failure: The coordinator’s failure can halt the process.

-

-

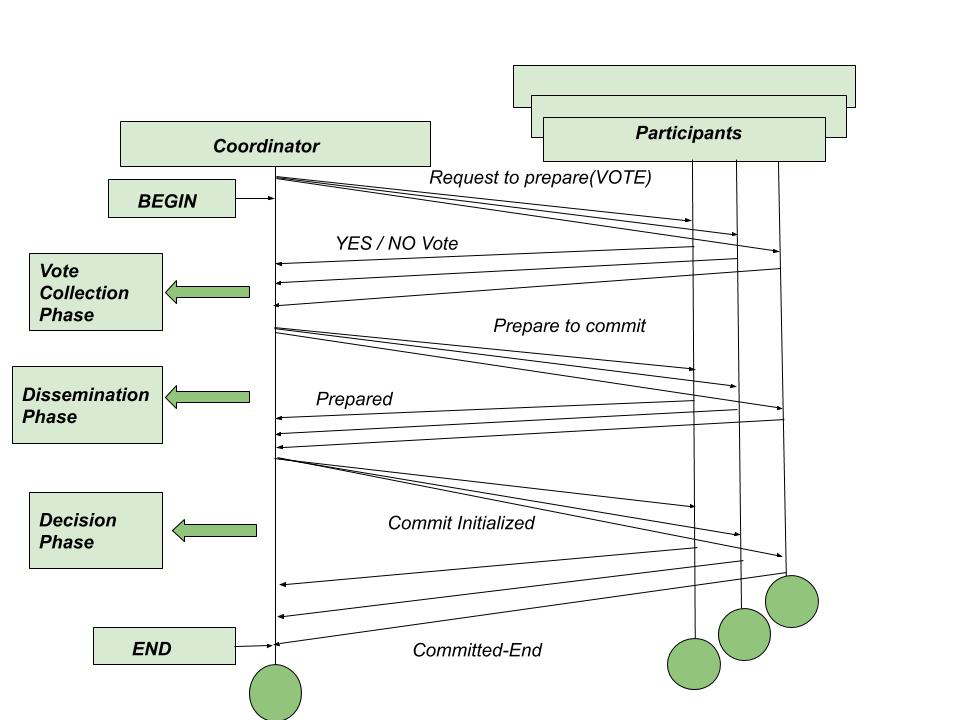

Three-Phase Commit (3PC):

-

What It Is: An extension of 2PC designed to address the blocking problem.

-

How It Works: 3PC adds an extra phase to avoid blocking, making it more resilient to coordinator failures:

-

Phase 1 (Prepare Phase): Same as 2PC—the coordinator asks sites to prepare and vote.

-

Phase 2 (Pre-Commit Phase): If all sites vote “yes,” the coordinator sends a “pre-commit” message. Sites acknowledge this and prepare to commit but don’t yet finalize. This phase ensures all sites agree on the outcome.

-

Phase 3 (Commit/Abort Phase): The coordinator sends a “commit” message (or “abort” if needed), and sites finalize the transaction.

-

Key Difference: If the coordinator fails after the pre-commit phase, surviving sites can elect a new coordinator, which can infer the transaction’s state (e.g., commit if pre-commit was sent) and proceed.

-

-

Example: In the same bank account update scenario, after both sites vote “yes,” the coordinator sends a pre-commit message. If the coordinator fails at this point, a new coordinator can take over and decide to commit based on the pre-commit state.

-

Pros: Reduces blocking compared to 2PC by allowing non-blocking recovery after coordinator failures.

-

Cons:

- More complex and introduces additional overhead (extra phase, more messages).

- Rarely used in practice due to this complexity and the fact that 2PC is often “good enough” with additional timeout mechanisms.

-

Key Considerations

-

Atomicity in Distributed Systems: Commit protocols are essential because a distributed transaction involves multiple sites. Without a protocol like 2PC or 3PC, one site might commit while another aborts, leading to inconsistency.

-

Failure Handling:

- 2PC relies on logging (which you’re familiar with) to recover after failures. For example, if a site fails after voting “yes,” it can check its log upon restart to see if the transaction was committed or aborted.

- 3PC’s pre-commit phase helps mitigate blocking, but it doesn’t eliminate all issues (e.g., network partitions can still cause problems).

-

Practical Use: 2PC is the standard in most DDBS implementations (e.g., in systems like Apache Cassandra or Google Spanner with modifications). 3PC is more theoretical and less commonly used due to its overhead.

Recovery Protocols

Recovery Protocols in DDBSs

Recovery protocols in distributed database systems ensure the system can return to a consistent state after a failure (like site, network, or transaction failures).

-

Undo/Redo Logging in a Distributed Context:

-

What It Is: This builds on the logging you know—each site logs transaction operations (e.g., “before” and “after” images of data changes) to enable recovery.

-

How It Works in DDBSs:

- Each site maintains its own log for local transactions.

- The coordinator (from commit protocols like 2PC) also logs the global transaction state (e.g., prepare, commit, or abort decisions).

- After a failure:

- Undo: Rolls back incomplete transactions by reverting to the “before” state in the log.

- Redo: Reapplies committed transactions using the “after” state to ensure durability.

-

Example: A transaction updates a customer record across two sites. If one site fails after voting “yes” in 2PC but before committing, it uses its log upon restart to redo the committed changes (if the coordinator logged a commit) or undo them (if an abort was logged).

-

Distributed Aspect: The challenge is coordinating logs across sites to ensure all sites agree on the transaction’s outcome.

-

-

Distributed Recovery:

-

What It Is: A process where each site performs local recovery, but the system coordinates globally to maintain consistency across all sites.

-

How It Works:

-

Local Recovery: Each site uses its logs and checkpoints to recover its local database state (e.g., undoing uncommitted transactions, redoing committed ones).

-

Global Coordination: The coordinator ensures that all sites agree on the transaction’s final state (committed or aborted).

- If a site fails during a 2PC process, it checks the coordinator’s log (or asks surviving sites) to determine the transaction’s outcome.

-

Network Partitions: If sites can’t communicate due to a network failure, they may need to wait until connectivity is restored to finalize recovery.

-

-

Example: A transaction spans three sites, and one site fails mid-transaction. The failed site restarts, performs local recovery using its log, and then contacts the coordinator to confirm whether to commit or abort the transaction.

-

Key Challenge: Ensuring all sites reach a consistent state, even if some fail during recovery.

-

-

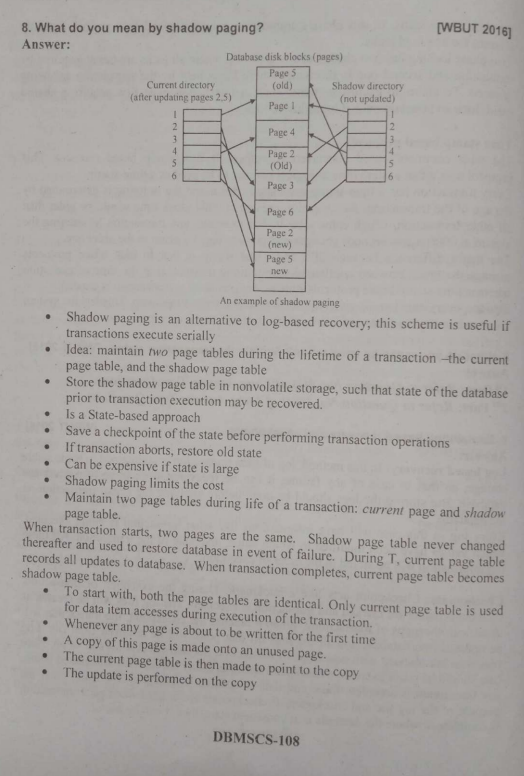

Shadow Paging in DDBSs:

-

What It Is: An alternative to logging where the system maintains a shadow copy of the database pages.

-

How It Works:

- During a transaction, updates are made to a copy of the database pages (the “shadow”).

- If the transaction commits, the shadow copy becomes the active database; if it aborts, the shadow is discarded, and the original remains unchanged.

- In a distributed context, each site manages its own shadow pages, and the coordinator ensures all sites agree on the commit/abort decision.

-

Example: A site updates a sales record in a shadow page. If the transaction commits across all sites, the shadow page replaces the original; if not, the shadow is discarded.

-

Pros: Simplifies recovery (no undo/redo needed for aborted transactions).

-

Cons: Higher overhead due to maintaining shadow copies, less commonly used in DDBSs compared to logging.

-

So shadow paging is an alternative to logging, and it helps since it basically creates a copy of a transaction which becomes active after committing, but gets discarded if the transaction aborts. The pros to this is that the original transaction is not affected and neither do we have to look up the log to rollback. This saves time.

-

Recovery Manager:

-

What It Is: A component responsible for coordinating recovery across sites.

-

How It Works:

- The recovery manager at each site handles local recovery (using logs or shadow paging).

- A global recovery manager (often part of the coordinator) ensures all sites agree on the transaction’s outcome.

- It uses the logs from the commit protocol (e.g., 2PC logs) to determine the state of in-progress transactions.

-

Example: After a site failure, the recovery manager at that site restarts, checks its local log, and contacts the global recovery manager to confirm the transaction’s state (e.g., “Did transaction T1 commit?”).

-

Role in 2PC/3PC: The recovery manager relies on the logs created during the commit protocol to resolve the state of transactions that were in progress during a failure.

-

Key Considerations

-

Relation to Commit Protocols: Recovery protocols work hand-in-hand with commit protocols (like 2PC and 3PC). The logs created during the commit process are used to determine whether to commit or abort a transaction after a failure.

-

Distributed Challenges:

- Ensuring global consistency requires coordination, which can be delayed by network issues.

- Partial failures (e.g., one site fails while others are operational) make recovery more complex than in centralized systems.