Module 4 -- Sparse Modeling and Estimation, Modeling Time-Series Data, Deep Learning and Feature Representation Learning.

Index

- Sparse Modeling

- Sparse Estimation

- Modeling Time Series and Sequence Data.#Pre-requisite -- Neural Networks and Deep Learning.

- The Humble Neural Network (Artificial Neural Networks - ANNs)

- The structure of a neural network.

- How Neural Networks learn -- Gradient Descent.

- Backpropagation, the heart of learning in neural networks

- Neural Networks Large Language Models

- Large Language Models How Transformers work.

- Transformers How the Attention mechanism works.

- Modeling Time Series data Pre-requisite -- Feature Representation Learning

- What is a Good Representation?

- Supervised Feature Representation Learning.

- 1. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

- How does the Convolutional Layer work?

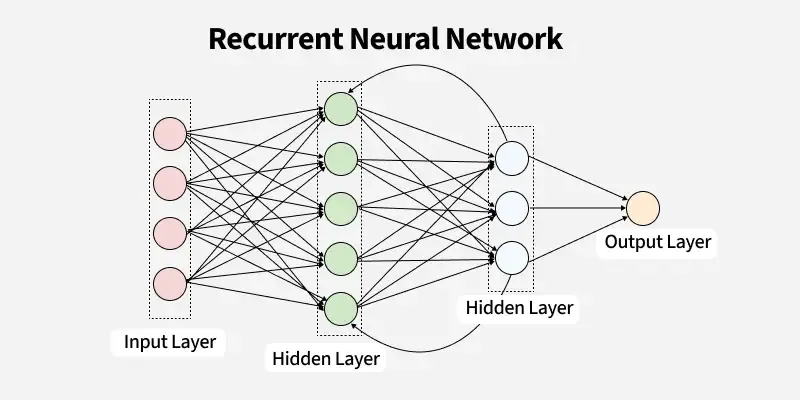

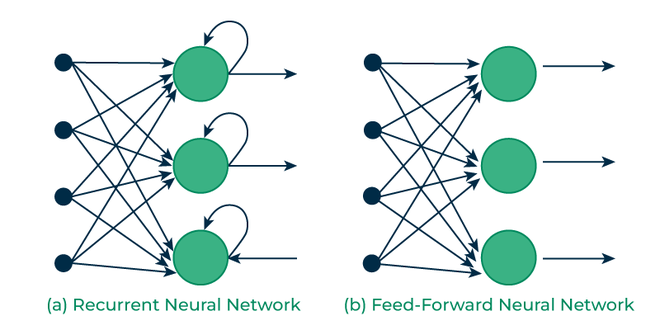

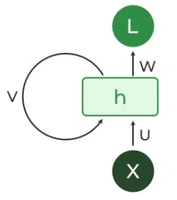

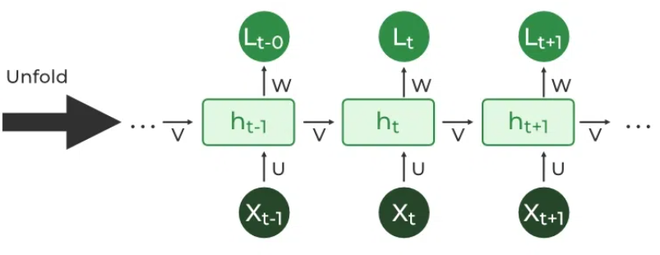

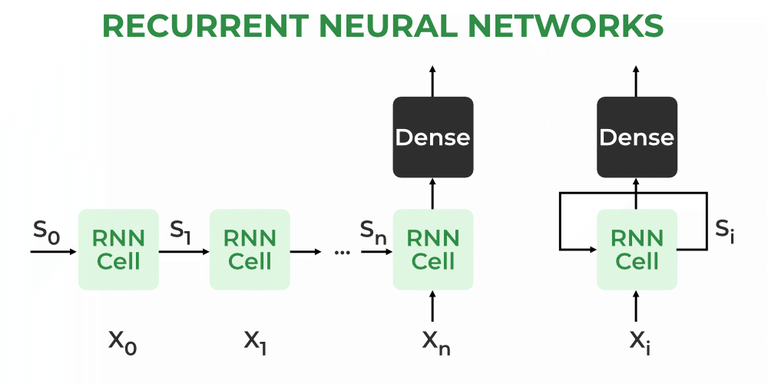

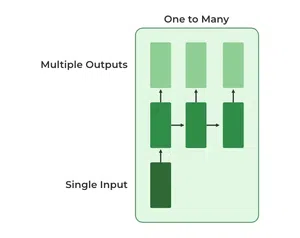

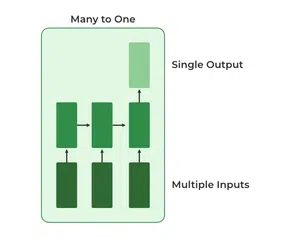

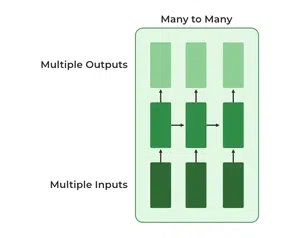

- 2. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs)

- How is this any different from Standard Neural Networks (the multi layered perceptron) or even the attention mechanism in Transformers?

- 3. Backpropagation through time (BPTT) explained.

- Unsupervised Feature Representation Learning

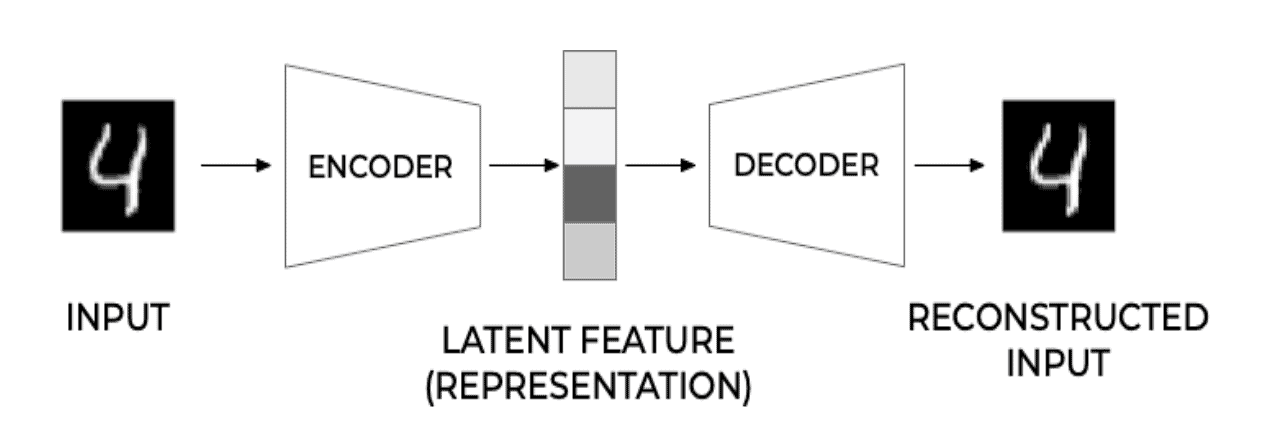

- 1. Autoencoders

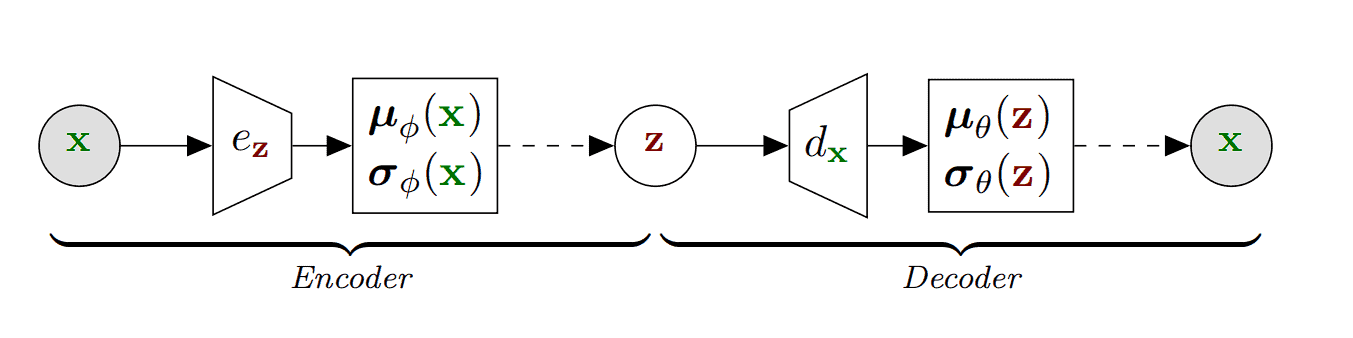

- Variational Autoencoders (VAEs)

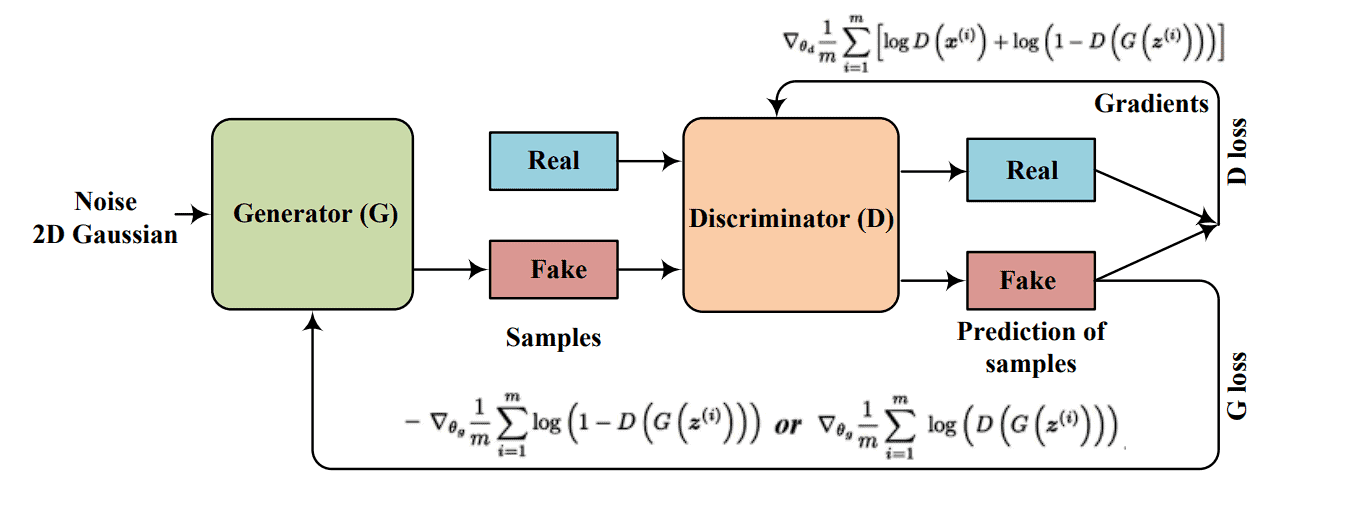

- 2. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

- 3. Transformers (but how they tie with encoders and decoders).

- 4. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs)

- Modeling Time Series Data (Finally)

- Classical Time-Series models

- Using deep learning models for modeling time series data.

Sparse Modeling

Had to dig up a lot of the internet for this:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oAVCEoySN4Y (it's an old 2015 NYU video, watch only if you can understand from that projector presentation).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SbU1pahbbkc (A very cool video explanation on Compressed Sensing (how images can be compressed and decompressed) (It utilizes the same concepts for Sparse Modeling))

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=inr-nGnVc0k (The mathematical foundation behind Compressed Sensing, also useful for Sparse Modeling)

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLMrJAkhIeNNRHP5UA-gIimsXLQyHXxRty (Full playlist)

The Core Idea of Sparse Modeling

-

You have some data (say images, audio, text, etc.).

-

You want to represent each data point efficiently using only a few building blocks.

-

Those building blocks are stored in a dictionary (matrix

W). -

Each data point is expressed as a combination of a few dictionary elements. The coefficients for that combination are stored in

Z. -

“Sparse” means most coefficients in

Zare zero → only a handful matter for each data point.

So instead of storing/using all features, we try to find a compressed, meaningful representation.

Example (Analogy)

Think of Lego:

-

You have a big Lego set (dictionary

W). -

To build a spaceship (your data

X), you only use a few blocks (coefficients inZ). -

You could dump the entire box to build it, but that’s wasteful. Sparse modeling forces you to use just the essential pieces.

How it Connects to Other Stuff You Know

-

If you force each data point to use only one block → that’s like K-means clustering.

-

If you force the blocks to be orthogonal and compact → that’s PCA (Principal Component Analysis).

-

Sparse modeling is in between → a flexible way to represent data with just enough pieces, but not too many.

How Do We Find the Sparse Codes (Z)?

This is the “hard” part, because deciding which few coefficients to keep is tricky.

Two families of approaches:

-

Greedy algorithms

-

Matching Pursuit, Orthogonal Matching Pursuit

-

They pick one block at a time, improving the fit step by step.

-

Fast but approximate.

-

-

Relaxed optimization (L1 minimization)

-

Replace the “count non-zeros” rule with “penalize large coefficients.”

-

Leads to convex optimization → solvable with algorithms like LASSO, ISTA (Iterative Shrinkage-Thresholding Algorithm), FISTA (fast version).

-

More accurate but slower.

-

(We don't need to delve in too deep into all these algorithms, only one will do.)

Why Bother?

Sparse modeling works surprisingly well for:

- Image denoising (remove noise but keep structure).

- Super-resolution (making images sharper).

- Feature extraction in recognition tasks (faces, objects).

- Learning compact, interpretable representations.

It’s used because it gives state-of-the-art results in many practical tasks.

Sparse Modeling vs. Compressive Sensing

-

Compressive Sensing: Start with compressed data and try to reconstruct the full signal.

-

Sparse Modeling: Start with full data and try to find a sparse code (compressed representation).

-

Equations look similar, but the goals differ.

How to Think About It (without drowning in math)

- You have data

X. - You want

X ≈ W × Z(dictionary × sparse codes). - Constraint: each column of

Zshould have only a few nonzero entries. - Algorithms help you find good

WandZ.

Example (with full pre-requisites mentioned)

This example should hopefully clear up any and all confusions including the mathematical backend.

Pre-requisites we need (no crazy level math)

-

Linear algebra basics: what a matrix, vector, and basis are (We already know this from Module 4 -- Vector Spaces#Basis of a Vector Space)

-

Norms:

- L2 norm = sum of squares (least squares).

- L1 norm = sum of absolute values (promotes sparsity).

-

Optimization idea: we’re minimizing something subject to a constraint.

1. What’s the problem? (The underdetermined system)

Imagine you’re solving:

-

= the few measurements you collected (like a handful of random pixels). -

= the basis (e.g., Fourier or wavelet basis) that can represent your signal. -

= the sparse coefficient vector in that basis (only a few non-zeros). -

= the measurement/sampling matrix (which pixels or samples you actually observed).

Now:

has way fewer entries than . - That means there are infinitely many possible

that fit .

So how do we find the right

We do this with the help of something called "norms".

Before that, what exactly is the sparse coefficient vector (or sparse matrix)?

https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/machine-learning/sparse-matrix-in-machine-learning/

The sparse matrix is a matrix in which the vast majority of its elements are zero. Formally, a matrix is considered sparse if the number of the non-zero elements is much smaller compared to the total number of the elements in the matrix. The Sparse matrices can be very large but have only a few non-zero elements.

Characteristics of Sparse Matrices

- High Proportion of Zeroes: The defining feature of the sparse matrix is that most of its elements are zeros.

- Storage Efficiency: The Sparse matrices can be stored the more efficiently compared to dense matrices reducing the amount of the memory required.

- Computational Efficiency: The Operations on sparse matrices can be optimized by the focusing only on the non-zero elements.

Example

In this matrix, only two elements are non-zero (3 and 5) making it a sparse matrix with the 78% of the elements as zero.

🔹 Norms: Measuring Vector Size

==A norm is a function that tells you how “big” a vector is. ==

Different norms = different ways of measuring.

1. L2 Norm (a.k.a. Euclidean norm)

-

This is the standard length/distance you already know (Pythagoras).

-

Example:

2. L1 Norm (a.k.a. Manhattan norm)

-

Think of walking on a grid city like Manhattan — distance = sum of absolute steps.

-

Example:

- In modeling: minimizing

tends to force some coefficients to become exactly zero → sparsity.

3. L0 “Norm” (not technically a norm, but used in sparse modeling)

- Example:

- This directly measures sparsity.

- Problem: minimizing

is computationally hard.

🚦 Why Norms Matter in Sparse Modeling

-

OLS regression uses L2 norm (minimizes squared error) → solution spreads across features.

-

Sparse modeling (LASSO, compressed sensing) uses L1 norm → solution naturally sets many coefficients to zero.

-

Ideally, we’d want to minimize L0 norm (true sparsity), but that’s infeasible.

So the trick is:

→ efficient, yet still gives sparse solutions.

Example: Sparse Modeling with L2 vs L1

Suppose we want to solve the underdetermined system:

This has infinitely many solutions:

, etc.

We need to pick the “best” solution using a norm.

Case 1: Minimize L2 Norm

We want the solution with smallest

👉 The minimizer is

- Both coefficients are nonzero.

- L2 spreads weight evenly → not sparse.

Case 2: Minimize L1 Norm

We want the solution with smallest

👉 The minimizers are

x$$x = (1,0) \quad \text{or} \quad x = (0,1)$$

- One coefficient is zero.

- L1 promotes sparsity → exactly what we want in sparse modeling.

✅ Key Takeaway

-

L2 minimization → dense solutions (all features get small weights).

-

L1 minimization → sparse solutions (many weights forced to zero).

-

This is why LASSO (L1 penalty) is central in sparse modeling, while Ridge (L2 penalty) is not.

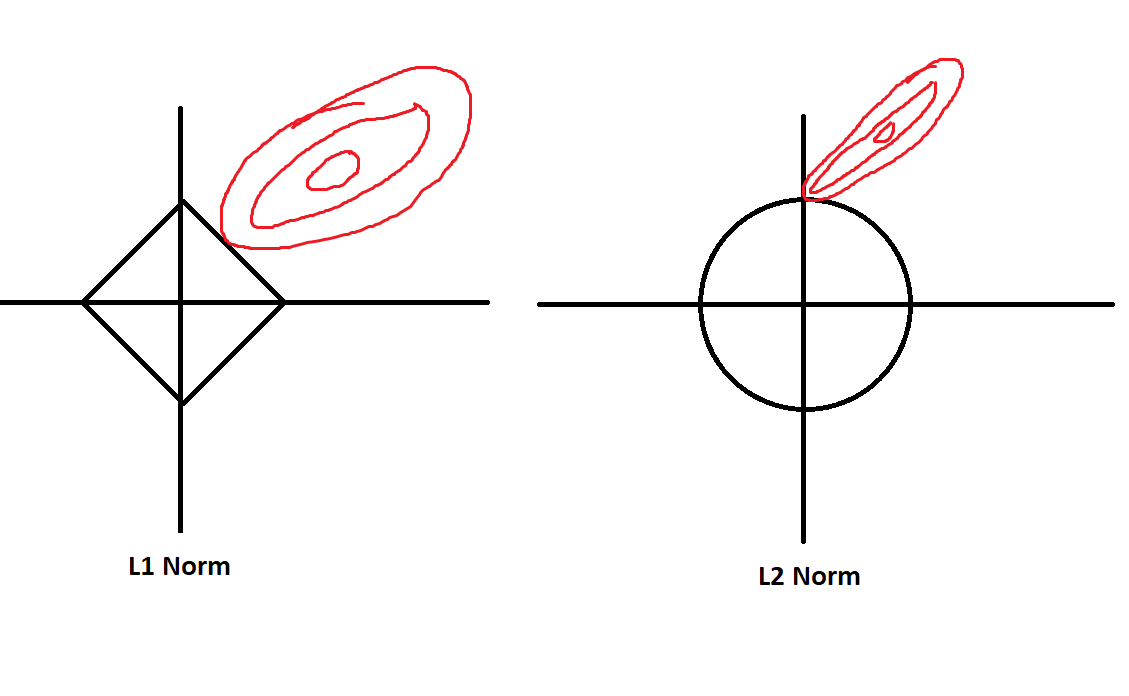

Geometric Intuition: How L1 and L2 norms look.

-

Ridge (L2): penalty is a circle → touches constraint line at non-sparse points.

-

Lasso (L1): penalty is a diamond → touches at corners (sparse solutions).

Sparse Estimation

Now this is the application of Sparse Modeling in ML : Sparse Estimation

Sparse estimation is the process of estimating regression coefficients while enforcing sparsity, typically using L1 penalties (Lasso).

Theoretical Basis -- The Problem

In regression, we usually want to fit a model:

where:

is the response vector (predicted output) is the design matrix (basically inputs) is the matrix of coefficients we want to estimate (the weights) : the noise (or errors)

Now the regression methods by default: the Standard Least Squared regression is

(don't focus on the equation, just try to understand what's the problem.)

The Ordinary Least Squares solution is"

Now the problem is that if there are too many inputs, the OLS is not unique, and thus the model can overfit (memorize inputs only) and doesn't reveal sparsity, and thus won't be able to generalize.

Sparse estimation -- The Solution

We often believe that only a few predictors are truly important.(Only a few weights are needed), so the rest unnecessary ones can be just turned off (set to zero).

So instead of just minimizing the squared error, we add a penalty to encourage sparsity in

This is done, using the norms as stated previously, mostly L1(Lasso) and L2(Ridge) norms.

Key difference:

-

Ridge shrinks coefficients, but rarely makes them exactly zero.

-

Lasso pushes some coefficients exactly to zero → gives sparse solutions.

This is the heart of sparse estimation in regression.

How do the norms come into play here?

Sparse estimation applies the norms on the coefficients as penalties.

Basically:

with the penalty being L1 or L2. That's it.

Minimal numerical example (no scary algebra)

Suppose we want to predict

After training with OLS, it gives us:

(both coefficients non-zero)

- If we apply ridge (L2) with large

:

(both smaller, but none exactly zero).

- If we apply lasso (L1) with large

:

(one coefficient killed off completely).

That’s sparse estimation in action: L1 gives feature selection, L2 just smooths.

So, big picture:

- You only need to know L1 = sparsity, L2 = shrinkage.

- Lasso = L1 penalty → sparse estimation.

- Ridge = L2 penalty → non-sparse but stable estimation.

👉 The scary equations are just the formal definition of “error + penalty.”

Modeling Time Series and Sequence Data.

Now here's where the real fun begins people. NEURAL NETWORKS!!

Pre-requisite -- Neural Networks and Deep Learning.

Deep Learning.

Before learning how to model different time series data with different types of neural networks, we need to know exactly what a neural network is under the hood, and how it works, how it learns.

This will tie back to almost everything we have learnt so far, so be sure to have learnt all the previous modules and that you have fairly good understanding of them.

Now, without further ado, let's unfurl the curtain on the next act, - The Humble Neural Network.

The Humble Neural Network (Artificial Neural Networks - ANNs)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aircAruvnKk&list=PLZHQObOWTQDNU6R1_67000Dx_ZCJB-3pi&index=1 (3blue1brown's series on Deep Learning and Neural Networks and how they work. It's an absolute watch, even better if you watch the videos first then come back here, since I too watched them first.)

1. But what is a neural network?

Instead of using a statistical ML model, like a Naive Bayes classifier, an SVM or other models like K-Means or clustering based models, we take the same let's say a linear regression model, but instead convert into a network of artificial neurons.

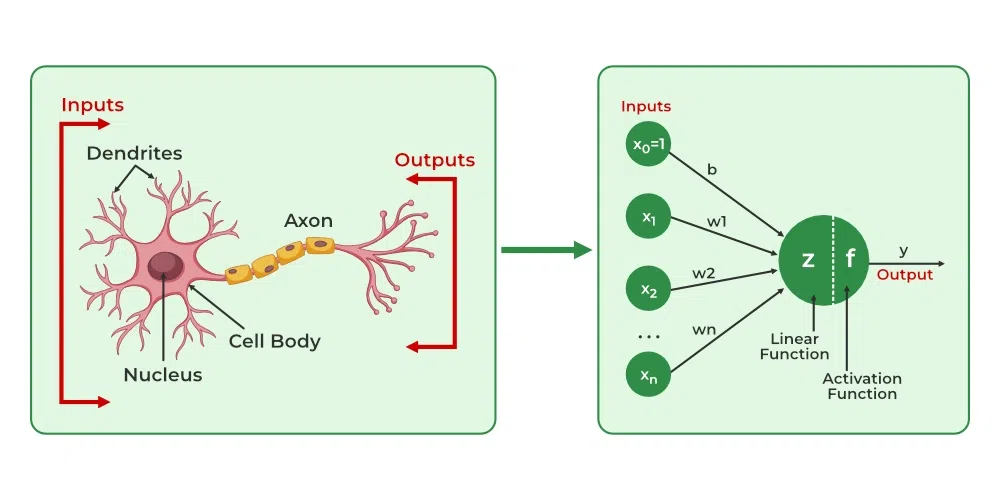

Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) are computer systems designed to mimic how the human brain processes information. Just like the brain uses neurons to process data and make decisions, ANNs use artificial neurons to analyze data, identify patterns and make predictions. These networks consist of layers of interconnected neurons that work together to solve complex problems. The key idea is that ANNs can "learn" from the data they process, just as our brain learns from experience.

So, how do these neurons function?

Unlike pure biological neurons which are binary neurons and are either on or off depending on the task, artificial neurons represent state values between 0 and 1, called activation states.

Artificial neurons vs Biological neurons

| Aspect | Biological Neurons | Artificial Neurons |

|---|---|---|

| Structure | Dendrites: Receive signals from other neurons. | Input Nodes: Receive data and pass it on to the next layer. |

| Cell Body (Soma): Processes the signals. | Hidden Layer Nodes: Process and transform the data. | |

| Axon: Transmits processed signals to other neurons. | Output Nodes: Produce the final result after processing. | |

| Connections | Synapses: Links between neurons that transmit signals. | Weights: Connections between neurons that control the influence of one neuron on another. |

| Learning Mechanism | Synaptic Plasticity: Changes in synaptic strength based on activity over time. | Backpropagation: Adjusts the weights based on errors in predictions to improve future performance. |

| Activation | Activation: Neurons fire when signals are strong enough to reach a threshold. | Activation Function: Maps input to output, deciding if the neuron should fire based on the processed data. |

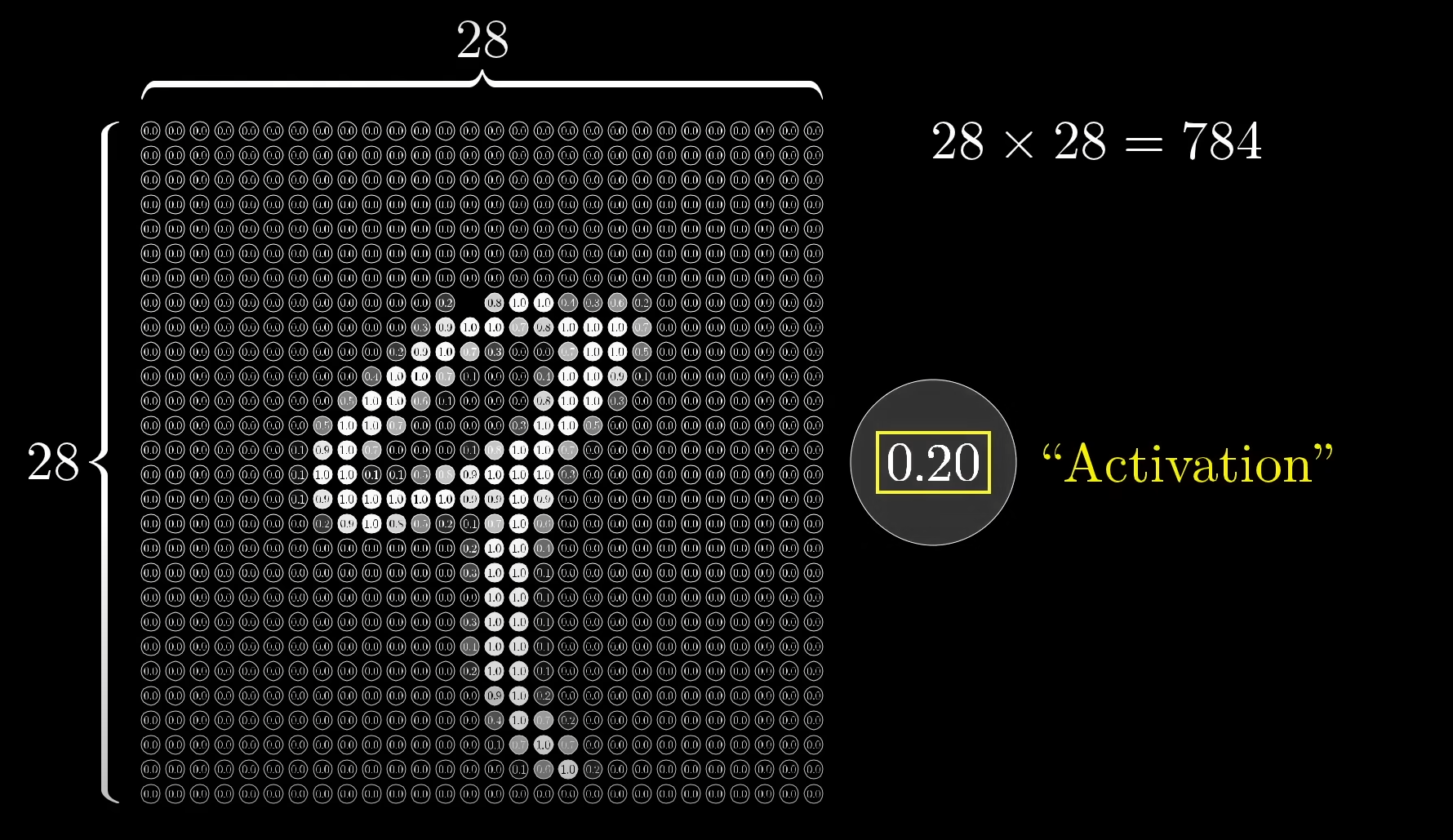

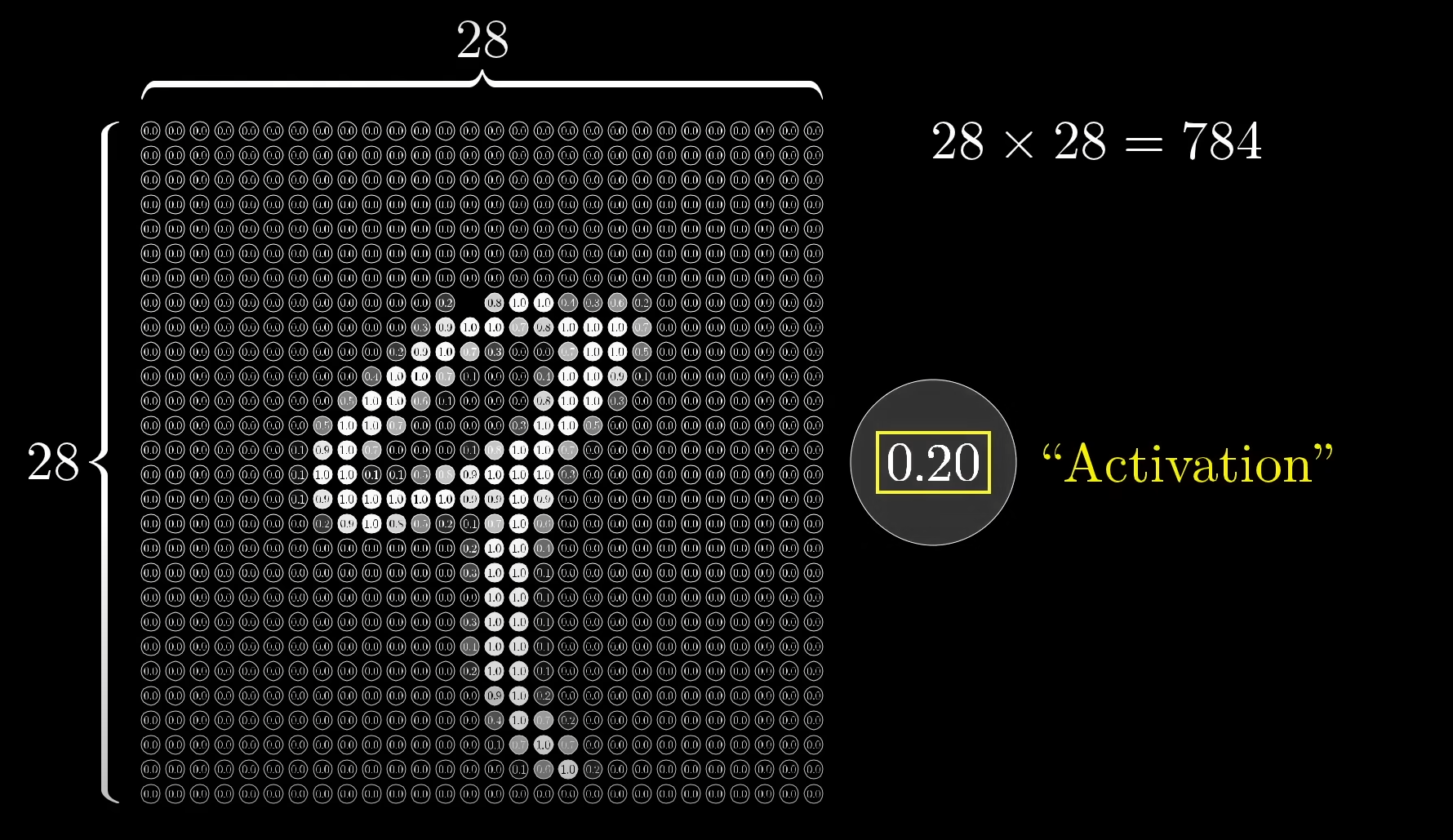

For example take this 28x28 pixel bit space for representing the image of a number via neurons.

You can see the image has a shadow as well, which is also represented by a group of neurons having different activation values. The closer they are to 1, indicates how positive the neuron is towards that action, or in this case, lighting up to represent a small pixel of the number's image.

The structure of a neural network.

Different neural networks like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Long Term Short Term Memory Neural Networks (LSTMNNs) all have different architectures.

So instead of focusing on them, we are going to start at the founding pioneer stage, the simple "perceptron". It was developed by Frank Rosenblatt in 1957 when Rosenblatt published pioneering work on the first machine learning algorithm for artificial neurons, known as the perceptron. He helped revolutionize the field of artificial intelligence through his work on enabling computers to learn from experience.

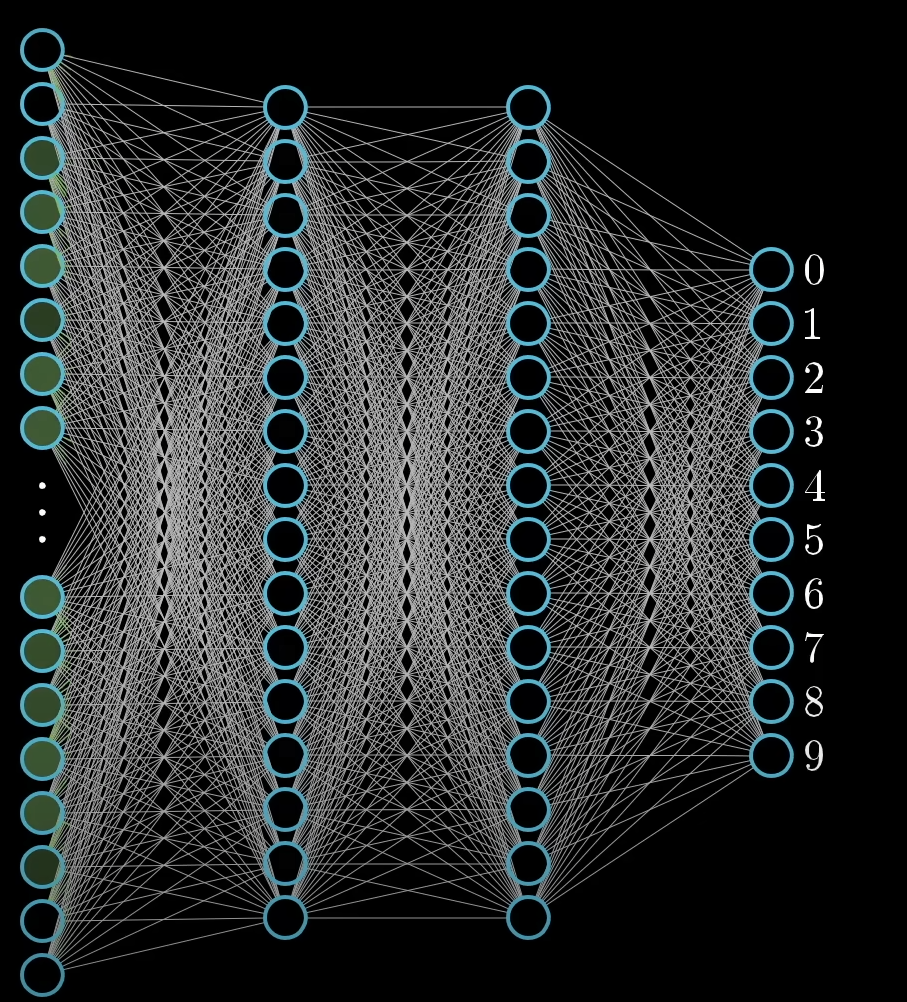

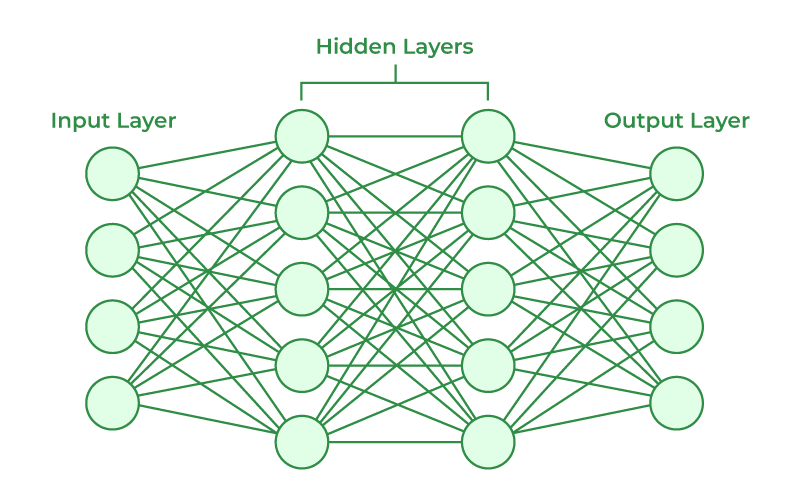

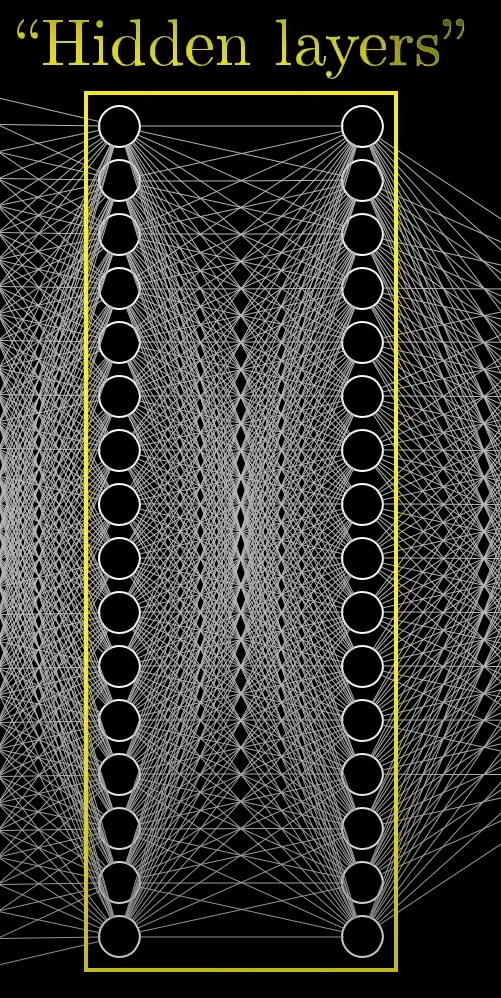

A simple neural network, the perceptron (and other neural nets) have 3 distinctions.

- The input layer: This is where the data is plugged in.

- The hidden layer (or layers): This is the where the magic happens.

- The output layer: This is where we get to see the output.

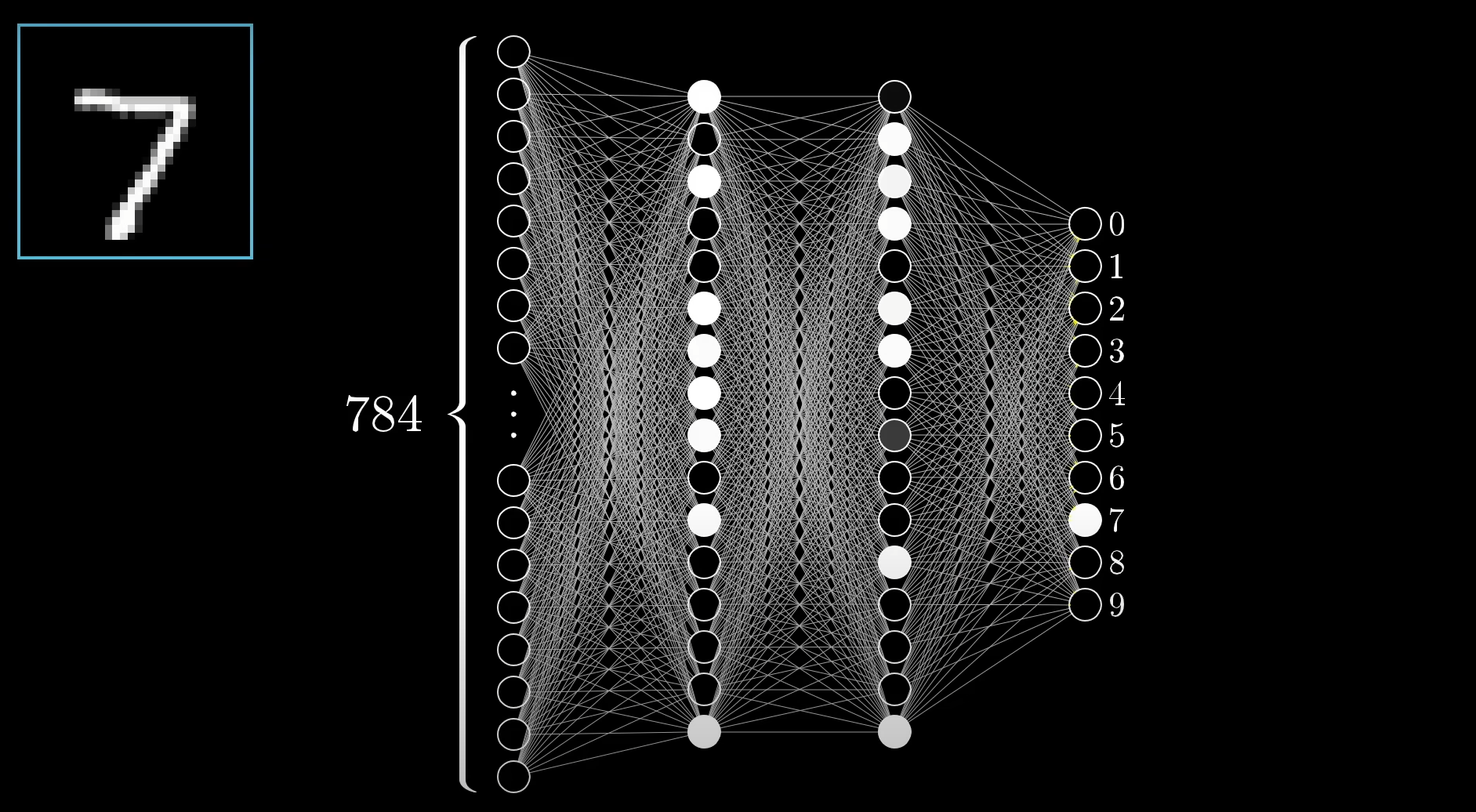

Now, in understanding how the perceptron works, let's take a very simple example dataset, which itself is inspired from the MNIST dataset (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/hojjatk/mnist-dataset). The MNIST database of handwritten digits has a training set of 60,000 examples, and a test set of 10,000 examples.

Now of course we won't be using that many examples. Instead let's just proceed with what 3blue1brown did in his video, to maintain continuity between my notes and the video.

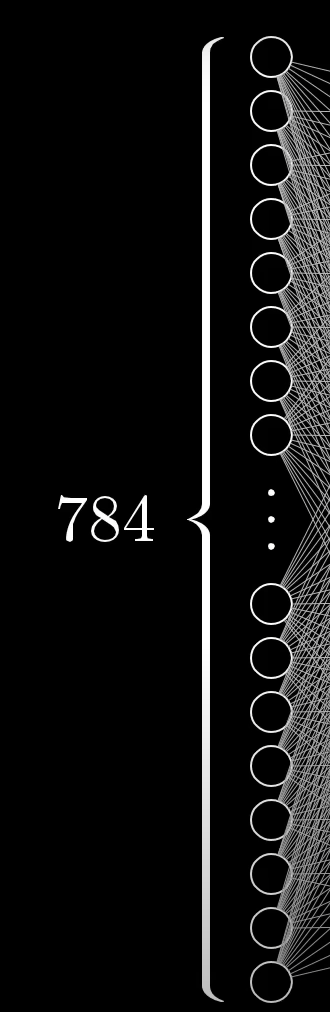

The input layer

For the first layer, let's take our 28x28 image pixel bit space, and to represent it as a layer of input neurons, we can simply multiply it, to get 784 which will be the number of neurons in our input layer.

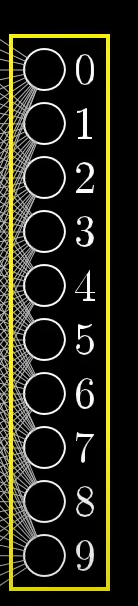

The output layer.

The output layer in this case, has only 9 neurons each representing a digit from 0-9.

The hidden layers

These are some in-between layers, whose purpose, we will know later on.

All-together

This is our full simple perceptron, in action, predicting some inputs to the output of the digit of 7.

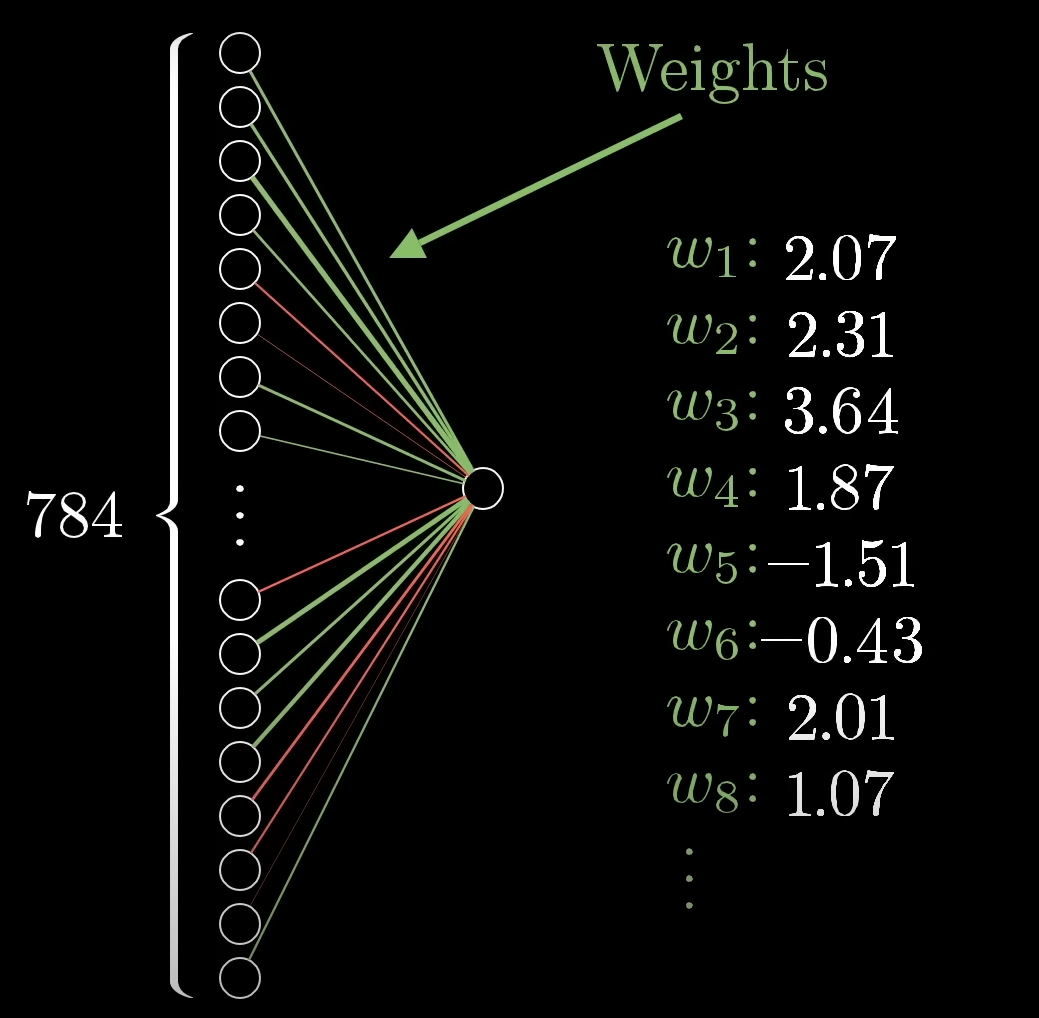

The weights, biases and activations of the neurons.

Now, since we already know that activation is the value of a neuron, which depicts how much the neuron is in favor of a particular pattern.

But, we don't have any control over how this activation value is set or even directly set them ourselves.

Instead what we have, is the control over the weights and biases.

The weights here, being the strength of the edges (or connections from one neuron to another)

And so, in place of our traditional regressions where we have

So this essentially becomes a weighted sum of all the activation values.

Now, if we can effectively control the weights from one layer to the next, we can influence the model on specific patterns leading to a very specific output.

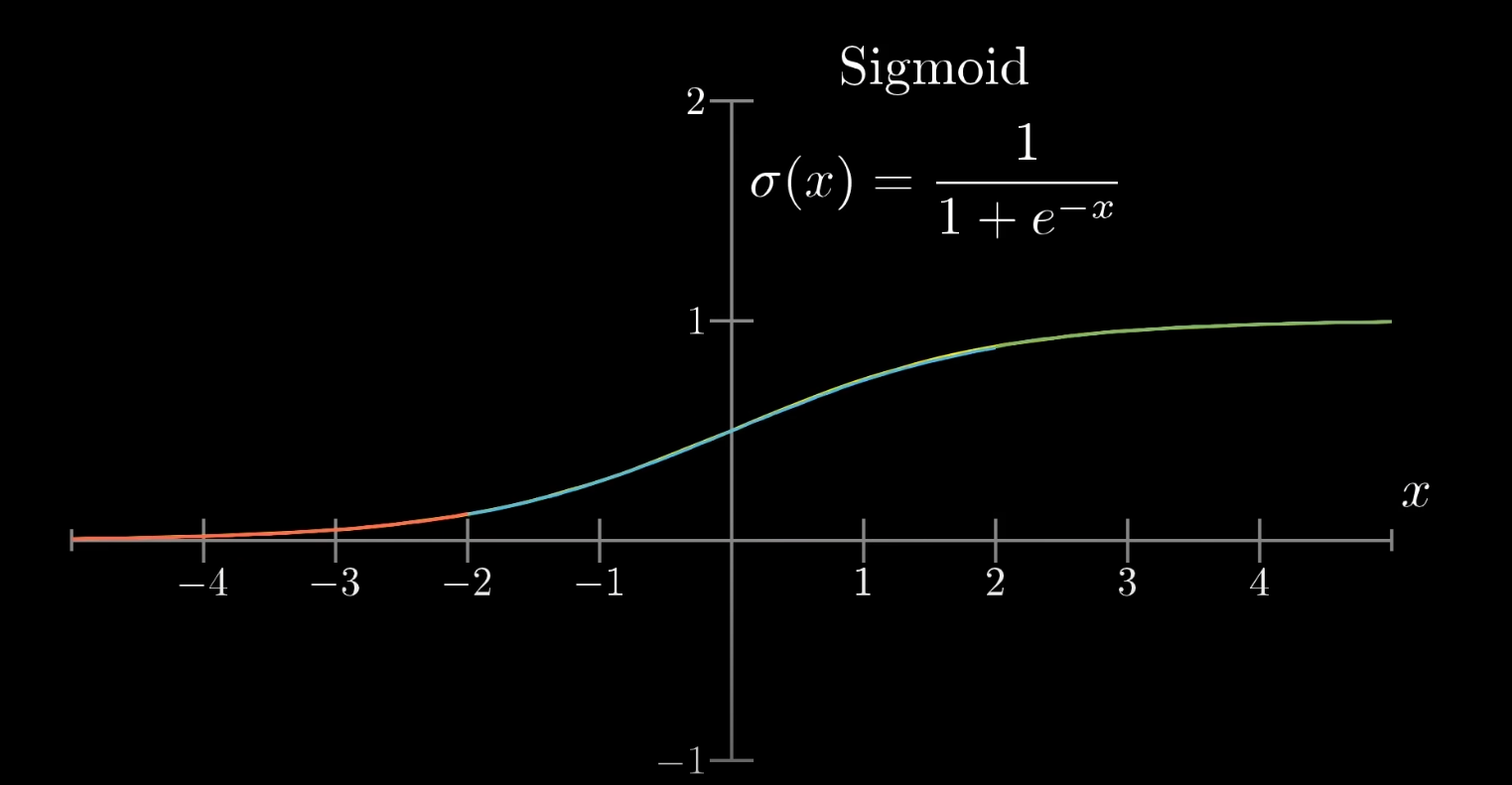

Now, in order to get a value only between

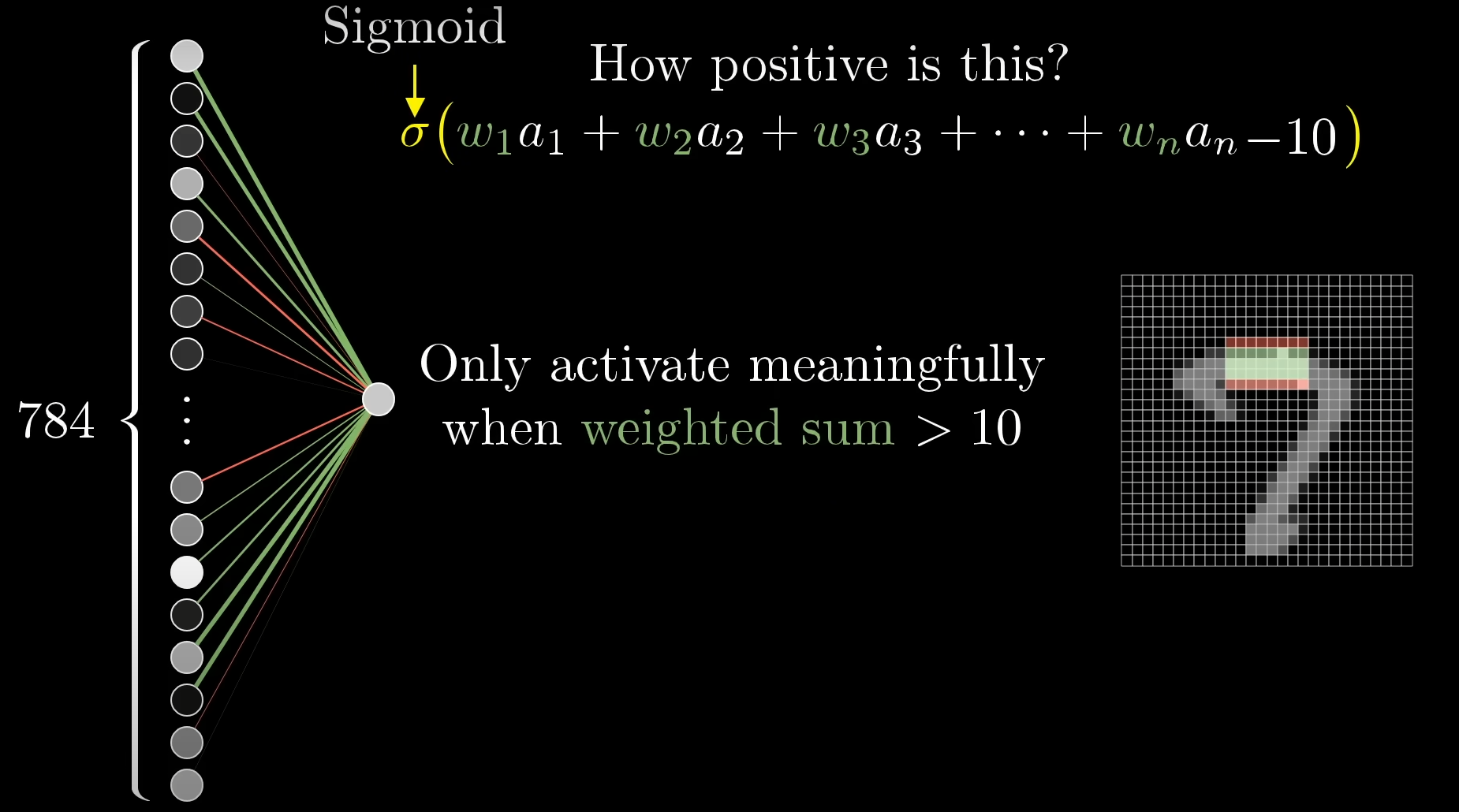

One very popular function to do that is the sigmoid kernel, which basically is:

which looks like this when graphed:

what this does is basically this:

Very negative values end up close to zero (values on the red segment)

Very positive values end up close to one (values on the green segment)

And values close to zero just end up increasing a bit (

So, if we apply :

We can clamp the output of the weighted sum between zero and one.

But that's not all, we also have the bias term remaining. This is the key motivating factor in nudging the activations towards something meaningful and not just random outputs.

Now what do we know of the bias so far? From Module 1 -- Supervised Learning -- Machine Learning#1. Linear Regression, we know that the bias is basically the default value of the equation when the inputs(features) of the equation are zero.

However that definition slightly changes when it comes to neural networks.

See, in order to effectively nudge the weighted sum towards something to get a meaningful activation value, we need to have a sort of threshold, a limiter, beyond which the weighted sum needs to exceed for the activation to signify a meaningful pattern of neurons to light up in the next layer, essentially and eventually influencing the final output.

This is the true purpose of the bias in the weighted sum here, since, the bias acts as the default values when all the other inputs (activations) are zero, which means that all the activations from the previous layer, times their respective weights, summed over, need to exceed that bias value to mean something.

Suppose, as shown in the video, we only want to neurons to activate when the weighted sum is greater than 10, so in order to do that, we purposely set the bias to

So, our weighted sum equation will end up as:

where

And all, this was for just one neuron. Yes, all this hassle, all this computation, is just for one single neuron, which will be connected to each and every other neuron in the next layer, and this will continue till it reaches the final layer. So yeah, that's an awful amount of computation to by hand, and even for just plain old CPUs with their sequential execution architectures, which will be ridiculously slow.

Common Activation Functions in ANNs

Activation functions are important in neural networks because they introduce non-linearity and helps the network to learn complex patterns. Lets see some common activation functions used in ANNs:

- Sigmoid Function: Outputs values between 0 and 1. It is used in binary classification tasks like deciding if an image is a cat or not.

- ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit): A popular choice for hidden layers, it returns the input if positive and zero otherwise. It helps to solve the vanishing gradient problem.

- Tanh (Hyperbolic Tangent): Similar to sigmoid but outputs values between -1 and 1. It is used in hidden layers when a broader range of outputs is needed.

- Softmax: Converts raw outputs into probabilities used in the final layer of a network for multi-class classification tasks.

- Leaky

ReLU: A variant ofReLUthat allows small negative values for inputs helps in preventing “dead neurons” during training.

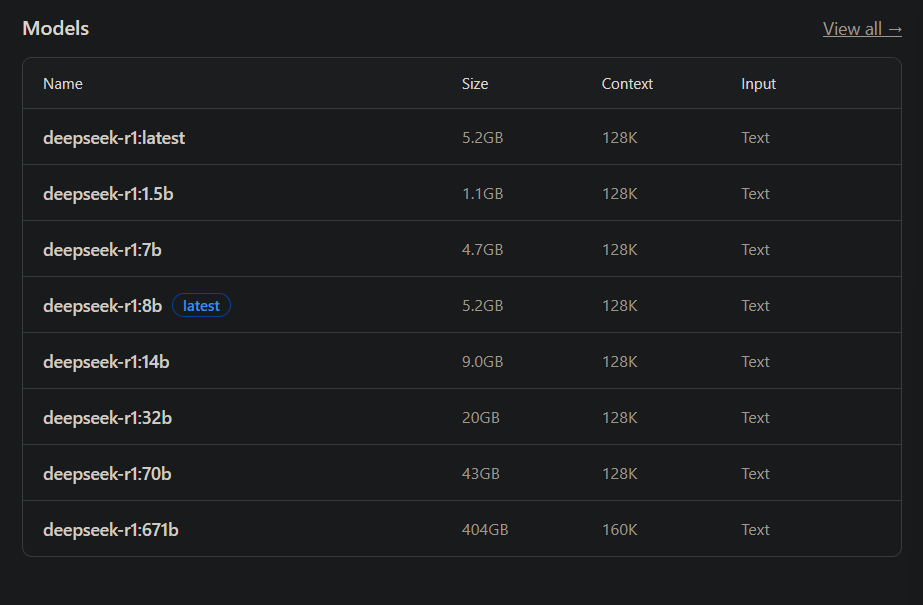

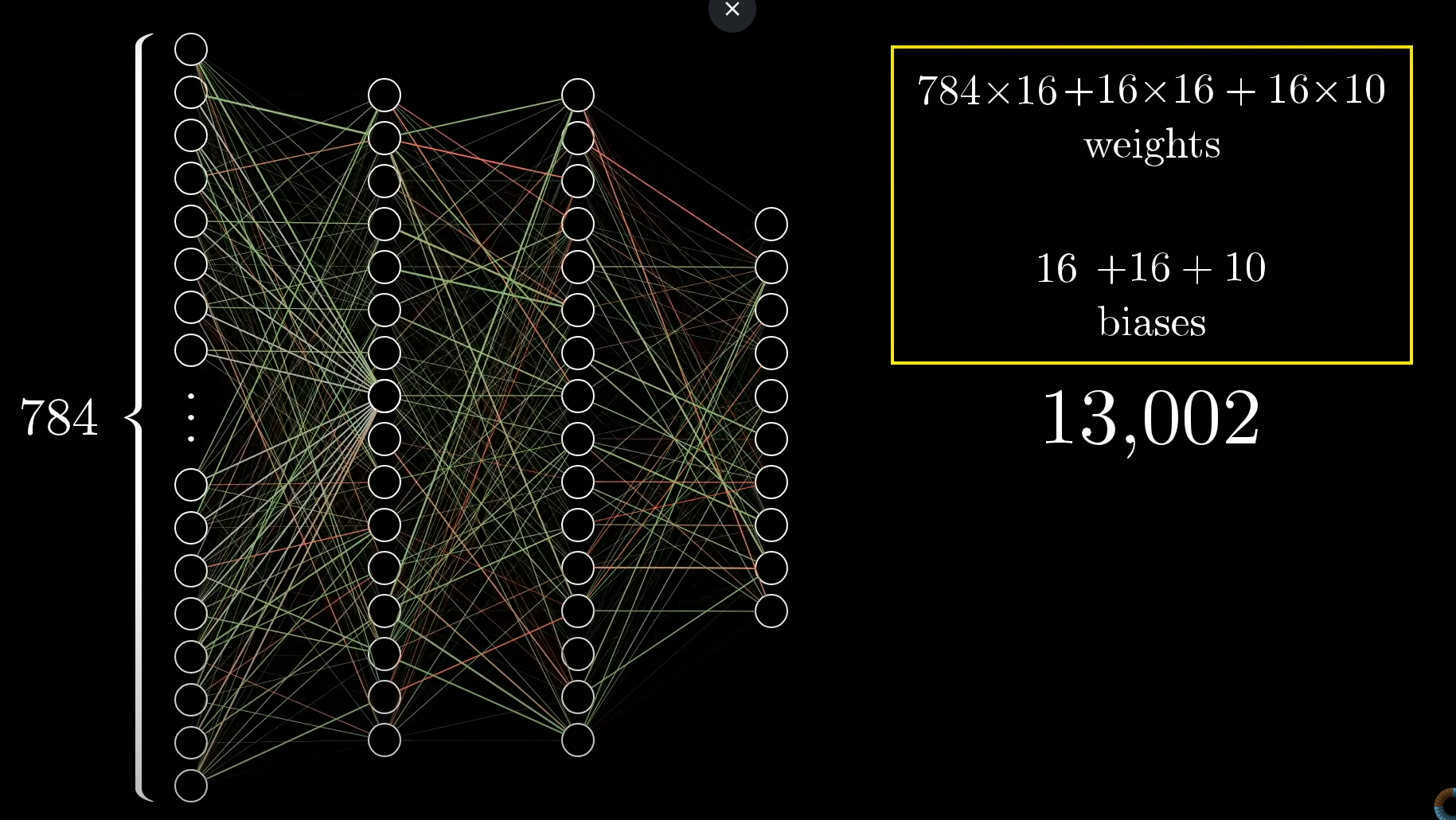

Calculating the total number of parameters of the neural network.

Now, you must have seen the term parameter quite often, if you have dabbled in running large language models locally on your pc.

For example, the most popular open source model, deepseek-r1:

https://ollama.com/library/deepseek-r1

And all other models like it, are represented in different parameters:

All have different number of "billion parameters" as represented in "1.5b, 7b, 8, 14b, 32, 70b and 671b" all with differing sizes, starting from the model with the lowest number of parameters having the lowest size, up to a gigantic size of 404GB for the 671 billion parameter model.

For our humble perceptron example though:

The math works like this:

784 neurons in the input layer is linked to the first hidden layer of 16 neurons, so we get

How Neural Networks learn -- Gradient Descent.

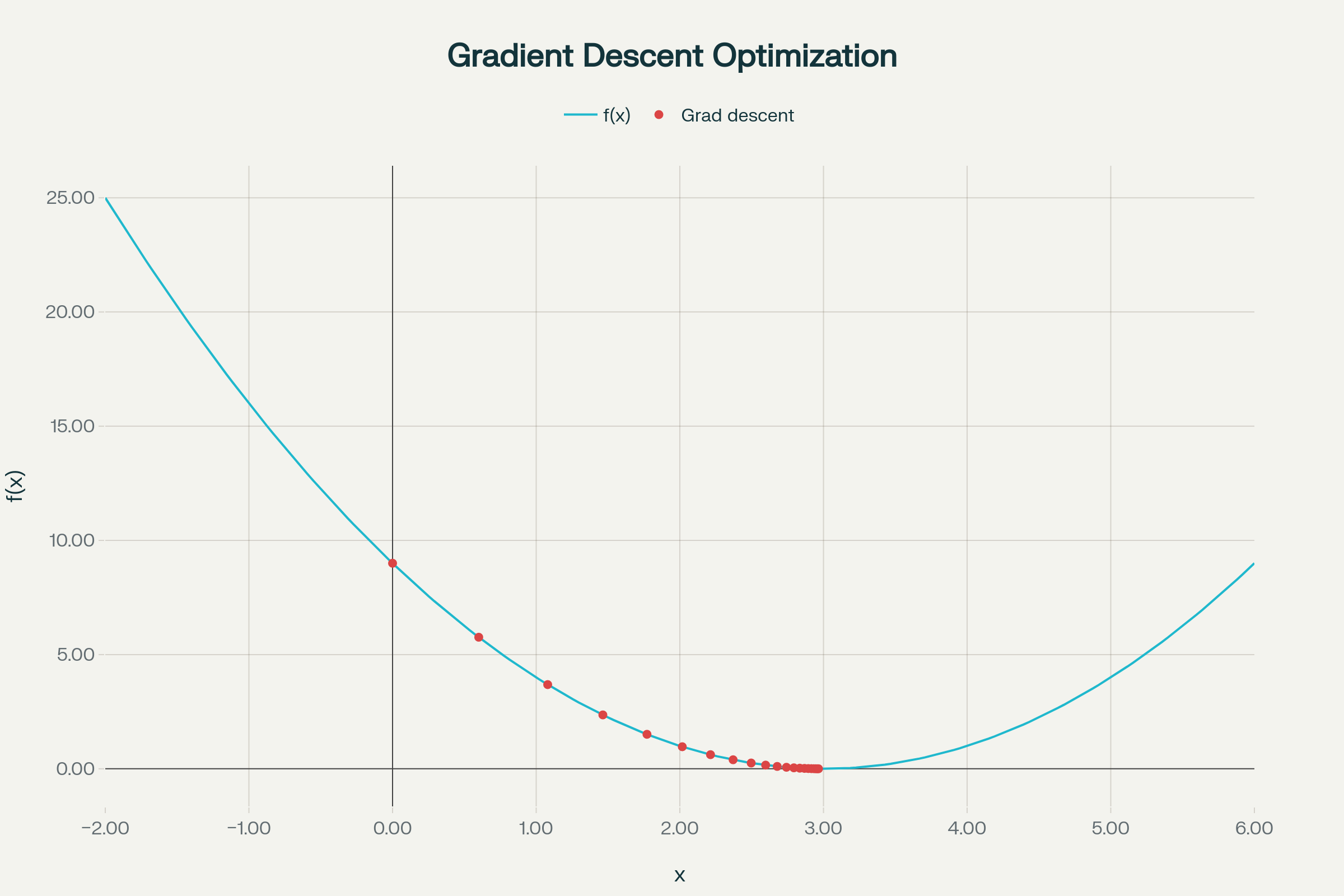

We already once covered the Gradient Descent method back in Module 2 -- Unsupervised Learning -- Machine Learning#Methods of matrix completion.#1. Gradient Descent

Still, let's recap. However, if you are already confident in Gradient Descent, you can skip ahead to How this ties to learning in Neural Networks.

What is Gradient Descent?

Gradient Descent is an iterative optimization algorithm widely used in machine learning to minimize loss (cost) functions.

The core idea:

- Start at a random point (guess for parameters/weights).

- Move in the direction of steepest descent (the negative of the gradient).

- Keep repeating until you reach the minimum or can't get lower.

It’s like walking downhill: you keep stepping in the direction that slopes most steeply down, each step being proportional to how steep the surface is beneath your feet.

Quick Numerical Example

Of course, we need to route through a pre-requisite example of how to find the gradient vector of a scalar field first, just to recap everything.

The gradient of a scalar field

For a 2D scalar field, that would be :

A small example:

Let's say we have a scalar function:

We have to find it's gradient at points

Finding each partial derivative:

Final gradient:

The algorithm of Gradient Descent, with a step-by-step example.

Gradient descent, in short, is just the negative of the gradient.

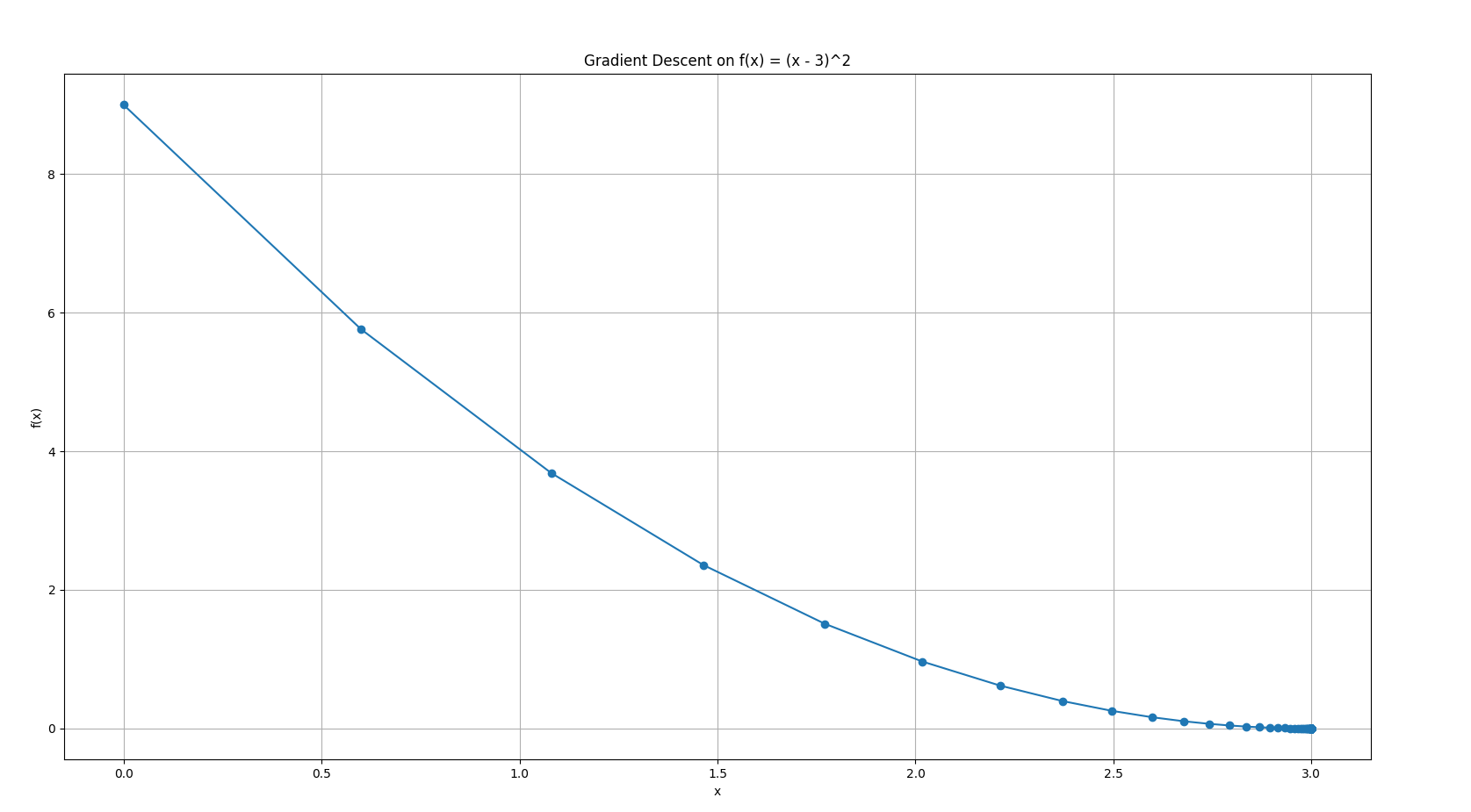

Let's minimize a simple function:

- This is a parabola, shaped like a bowl, whose minimum is at

, where .

You might be wondering as to how to figure out the minimum of this function?

Simple, just put the value in

Step 1: Start with an initial guess.

Let's say

Step 2: Calculate gradient (slope)

For our function, the gradient is:

which would be:

Step 3: Iterate, update the parameter.

The update rule is:

where

Here

So a more better version of this would be:

where the original function

Step 4: Repeat till you get

Some example iterations would include

Iteration 1: x = 0.6000000000000001

Iteration 2: x = 1.08

Iteration 3: x = 1.464

Iteration 4: x = 1.7711999999999999

Iteration 5: x = 2.01696

Iteration 6: x = 2.213568

Iteration 7: x = 2.3708544

Iteration 8: x = 2.49668352

Iteration 9: x = 2.597346816

Iteration 10: x = 2.6778774528

Iteration 11: x = 2.74230196224

Iteration 12: x = 2.793841569792

Iteration 13: x = 2.8350732558336

Iteration 14: x = 2.86805860466688

Iteration 15: x = 2.894446883733504

Iteration 16: x = 2.9155575069868034

Iteration 17: x = 2.932446005589443

Iteration 18: x = 2.945956804471554

Iteration 19: x = 2.9567654435772432

Iteration 20: x = 2.9654123548617948

Iteration 21: x = 2.9723298838894356

Iteration 22: x = 2.9778639071115487

Iteration 23: x = 2.982291125689239

Iteration 24: x = 2.985832900551391

Iteration 25: x = 2.988666320441113

Iteration 26: x = 2.9909330563528904

Iteration 27: x = 2.9927464450823122

Iteration 28: x = 2.99419715606585

Iteration 29: x = 2.99535772485268

Iteration 30: x = 2.996286179882144

Iteration 31: x = 2.997028943905715

Iteration 32: x = 2.9976231551245722

Iteration 33: x = 2.9980985240996576

Iteration 34: x = 2.9984788192797263

Iteration 35: x = 2.998783055423781

Iteration 36: x = 2.999026444339025

Iteration 37: x = 2.99922115547122

Iteration 38: x = 2.9993769243769757

Iteration 39: x = 2.9995015395015807

Iteration 40: x = 2.9996012316012646

Iteration 41: x = 2.9996809852810116

Iteration 42: x = 2.999744788224809

Iteration 43: x = 2.9997958305798473

Iteration 44: x = 2.999836664463878

Iteration 45: x = 2.9998693315711025

Iteration 46: x = 2.999895465256882

Iteration 47: x = 2.9999163722055053

Iteration 48: x = 2.999933097764404

Iteration 49: x = 2.9999464782115233

Iteration 50: x = 2.9999571825692186

Iteration 51: x = 2.999965746055375

Iteration 52: x = 2.9999725968443

Iteration 53: x = 2.99997807747544

Iteration 54: x = 2.999982461980352

Iteration 55: x = 2.9999859695842814

Iteration 56: x = 2.999988775667425

Iteration 57: x = 2.99999102053394

Iteration 58: x = 2.999992816427152

Iteration 59: x = 2.9999942531417214

Iteration 60: x = 2.999995402513377

Iteration 61: x = 2.9999963220107015

Iteration 62: x = 2.999997057608561

Iteration 63: x = 2.999997646086849

Iteration 64: x = 2.999998116869479

Iteration 65: x = 2.9999984934955832

Iteration 66: x = 2.9999987947964666

Iteration 67: x = 2.999999035837173

Iteration 68: x = 2.9999992286697386

Iteration 69: x = 2.999999382935791

Iteration 70: x = 2.9999995063486327

Iteration 71: x = 2.999999605078906

Iteration 72: x = 2.9999996840631247

Iteration 73: x = 2.9999997472504996

Iteration 74: x = 2.9999997978004

Iteration 75: x = 2.9999998382403197

Iteration 76: x = 2.999999870592256

Iteration 77: x = 2.999999896473805

Iteration 78: x = 2.9999999171790437

Iteration 79: x = 2.999999933743235

Iteration 80: x = 2.999999946994588

Iteration 81: x = 2.99999995759567

Iteration 82: x = 2.999999966076536

Iteration 83: x = 2.9999999728612288

Iteration 84: x = 2.999999978288983

Iteration 85: x = 2.9999999826311865

Iteration 86: x = 2.999999986104949

Iteration 87: x = 2.9999999888839595

Iteration 88: x = 2.9999999911071678

Iteration 89: x = 2.9999999928857344

Iteration 90: x = 2.9999999943085873

Iteration 91: x = 2.9999999954468697

Iteration 92: x = 2.999999996357496

Iteration 93: x = 2.9999999970859967

Iteration 94: x = 2.999999997668797

Iteration 95: x = 2.9999999981350376

Iteration 96: x = 2.99999999850803

Iteration 97: x = 2.999999998806424

Iteration 98: x = 2.9999999990451394

Iteration 99: x = 2.9999999992361115

Iteration 100: x = 2.9999999993888893

Iteration 101: x = 2.9999999995111115

Iteration 102: x = 2.9999999996088893

Iteration 103: x = 2.9999999996871116

Iteration 104: x = 2.999999999749689

Iteration 105: x = 2.9999999997997513

Iteration 106: x = 2.999999999839801

Iteration 107: x = 2.9999999998718407

Iteration 108: x = 2.9999999998974727

Iteration 109: x = 2.999999999917978

Iteration 110: x = 2.9999999999343823

Iteration 111: x = 2.999999999947506

Iteration 112: x = 2.9999999999580047

Iteration 113: x = 2.9999999999664038

Iteration 114: x = 2.999999999973123

Iteration 115: x = 2.999999999978498

Iteration 116: x = 2.9999999999827986

Iteration 117: x = 2.999999999986239

Iteration 118: x = 2.999999999988991

Iteration 119: x = 2.999999999991193

Iteration 120: x = 2.999999999992954

Iteration 121: x = 2.999999999994363

Iteration 122: x = 2.9999999999954907

Iteration 123: x = 2.9999999999963927

Iteration 124: x = 2.9999999999971143

Iteration 125: x = 2.9999999999976916

Iteration 126: x = 2.9999999999981535

Iteration 127: x = 2.999999999998523

Iteration 128: x = 2.9999999999988183

Iteration 129: x = 2.9999999999990545

Iteration 130: x = 2.9999999999992437

Iteration 131: x = 2.999999999999395

Iteration 132: x = 2.999999999999516

Iteration 133: x = 2.9999999999996128

Iteration 134: x = 2.99999999999969

Iteration 135: x = 2.999999999999752

Iteration 136: x = 2.999999999999802

Iteration 137: x = 2.9999999999998415

Iteration 138: x = 2.999999999999873

Iteration 139: x = 2.9999999999998983

Iteration 140: x = 2.9999999999999187

Iteration 141: x = 2.999999999999935

Iteration 142: x = 2.999999999999948

Iteration 143: x = 2.9999999999999583

Iteration 144: x = 2.9999999999999667

Iteration 145: x = 2.9999999999999734

Iteration 146: x = 2.9999999999999787

Iteration 147: x = 2.999999999999983

Iteration 148: x = 2.9999999999999867

Iteration 149: x = 2.9999999999999893

Iteration 150: x = 2.9999999999999916

Iteration 151: x = 2.9999999999999933

Iteration 152: x = 2.9999999999999947

Iteration 153: x = 2.9999999999999956

Iteration 154: x = 2.9999999999999964

Iteration 155: x = 2.9999999999999973

Iteration 156: x = 2.999999999999998

Iteration 157: x = 2.9999999999999982

Iteration 158: x = 2.9999999999999987

Iteration 159: x = 2.999999999999999

Iteration 160: x = 2.999999999999999

I took the liberty to cook up a python script to see exactly in how many iterations we can get as close as possible to the minimum,

It took a total of 159 iterations to be exact. Which is why iterative methods are best left to computers, but the knowledge is still needed, hence why I added this method.

Step 5 : Plot the iterations.

Again, best left to computers.

- The blue curve is

. - Red dots show each gradient descent step.

- You see how the steps start large (when farther away and the slope is steep), and get smaller as you approach the minimum.

Or a shortened one:

Types of Gradient Descent

- Batch Gradient Descent: Compute the gradient using the whole dataset before each update.

- Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD): Update with the gradient from one example at a time.

- Mini-batch Gradient Descent: Updates with gradient from a small random subset (mini-batch); the most popular in practice.

How this ties to learning in Neural Networks

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IHZwWFHWa-w&list=PLZHQObOWTQDNU6R1_67000Dx_ZCJB-3pi&index=2

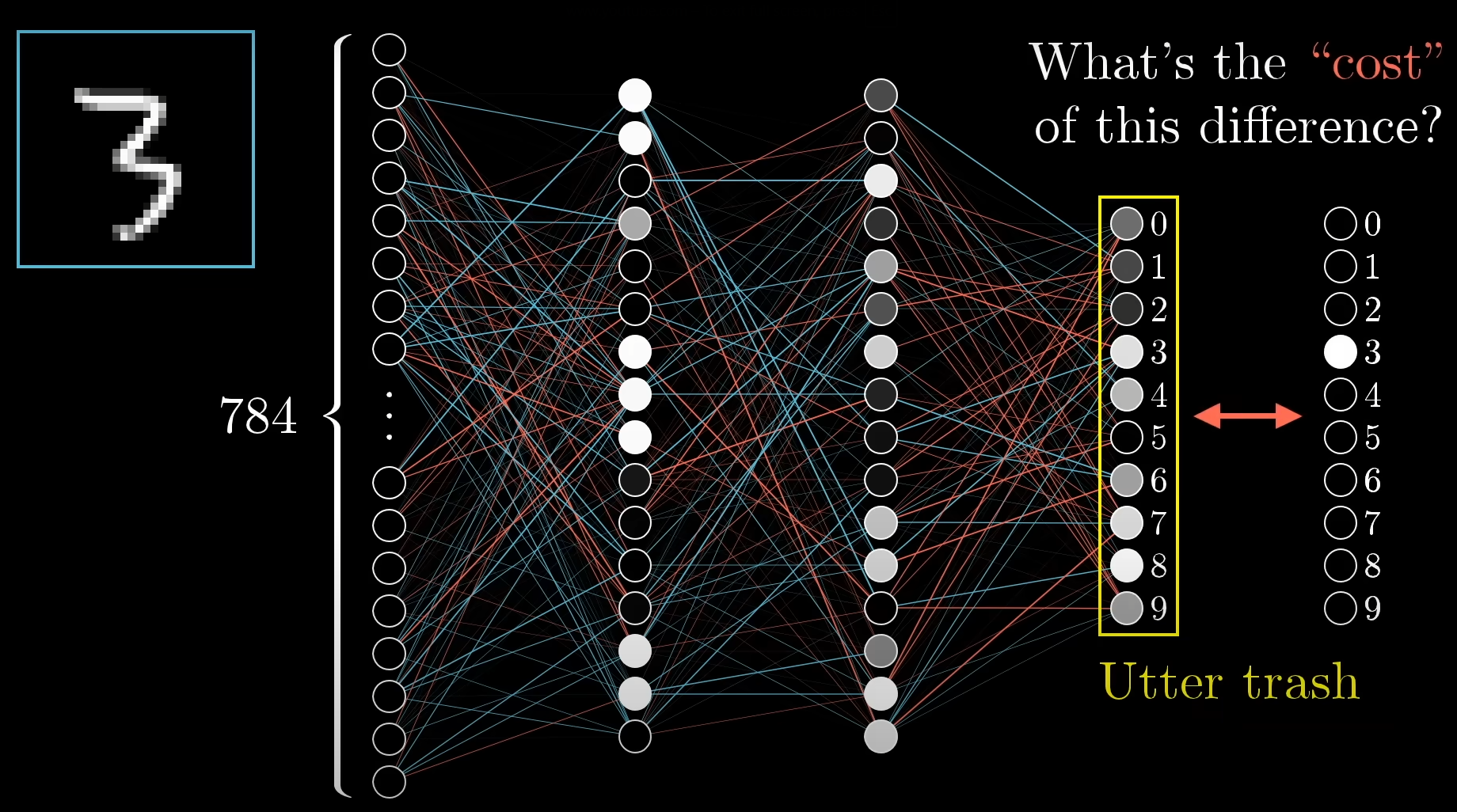

Referencing this video, take this picture for example:

We wanted the network to predict the given input image as the number "3", however, it instead gave various activation outputs for a lot of numbers, which becomes a hodgepodge.

So, how do we fix this, and instead of berating the network that it's trash, make it learn?

We do this by introducing cost functions. Why cost functions?

Let's head back to semester 4, Module 2 -- Search Strategies and Adversarial Search#Heuristic Search Strategies Informed search algorithms & Shortest Path Algorithms.

Core Idea: At each step, the algorithm selects the node that appears to lead to the goal state most quickly, according to the heuristic function. It essentially "greedily" chooses the path that seems best in the short term, without considering the long-term consequences.

In short, we incentivize the network to select a path that has a the lowest cost for it's intended pattern finding based on the input.

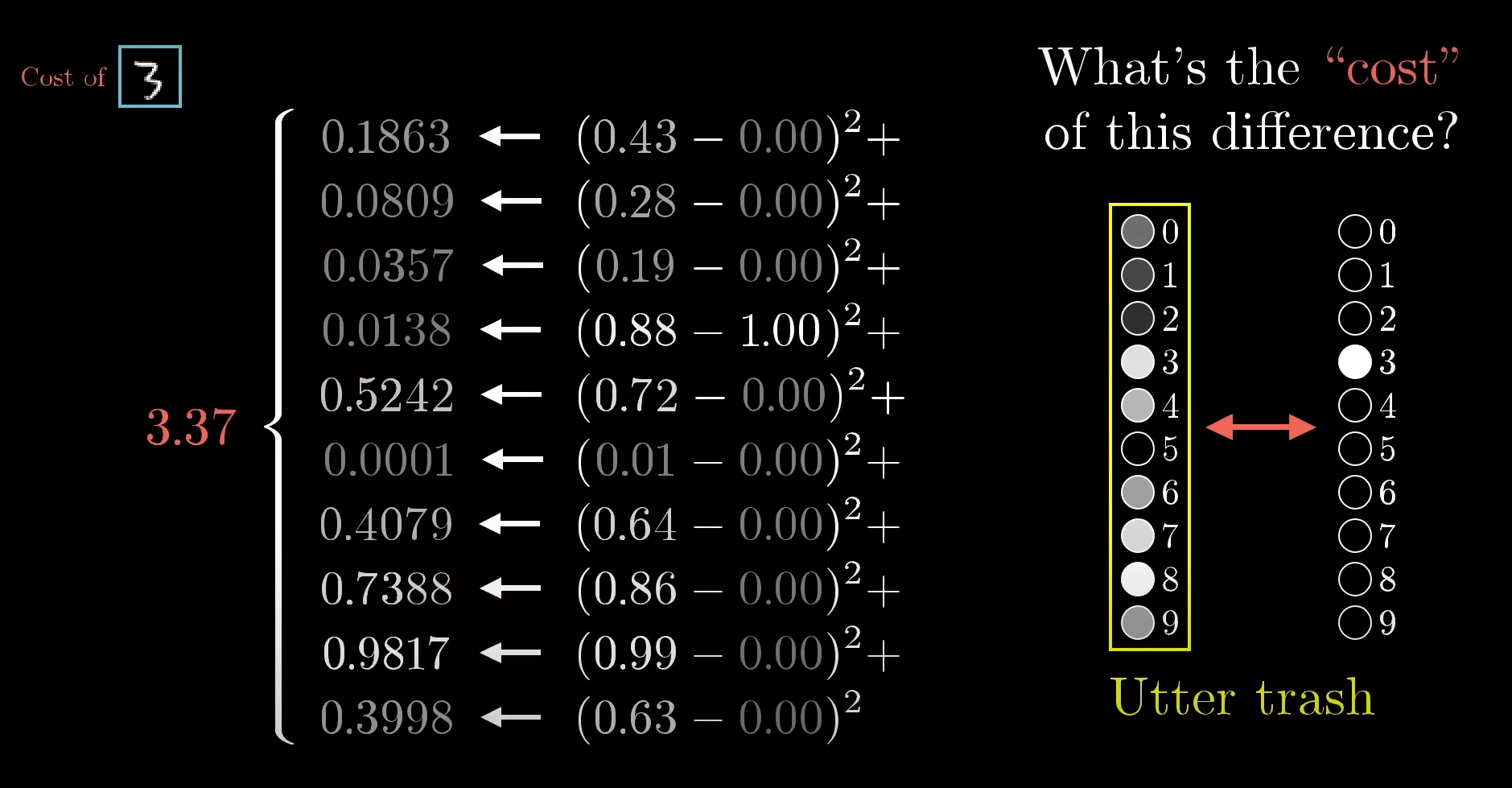

Now, what is this cost function? How do we get the desired heuristic cost values per output?

We can get that by adding up the squares of the differences of each output activation values which the network gives, from the desired output activation values we want the network to give for that specific output neuron.

So, for the third neuron, the activation value,

So by default the network will be incentivized to choose the path of neurons in the previous layer to give a very high activation value for this specific neuron, for the input 3.

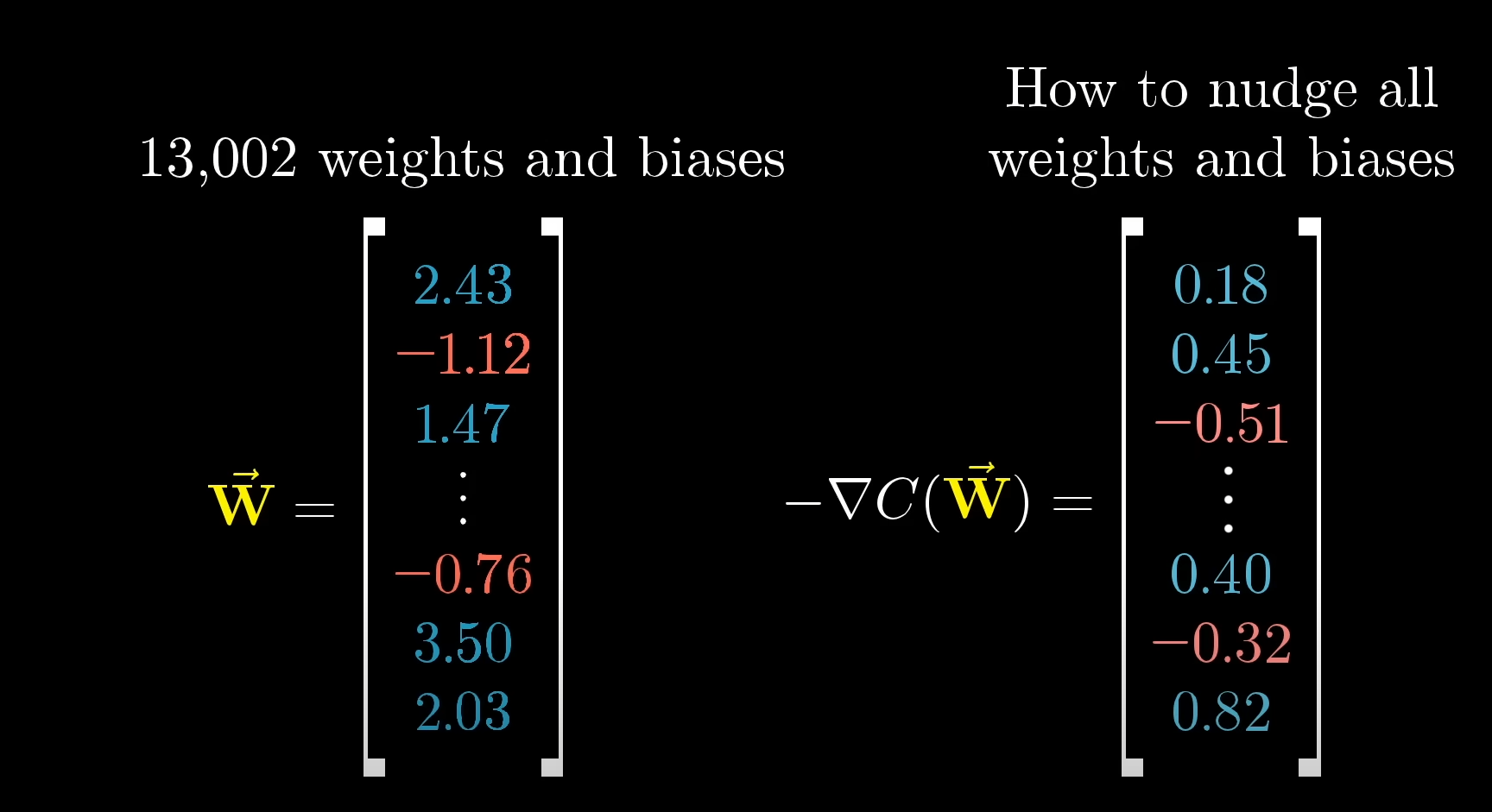

Now this looks good enough on the surface, but the cost function is mapped out across the entire network, so it's total number of inputs is basically the total number of parameters of the network, or, all of the total 13,002 weights and biases.

That's a lot of computation.

A common misconception

So, you might be thinking, since the cost function depends on all weights and biases, why can’t we just compute the exact weights that minimize the cost in one go (like solving equations), instead of iteratively doing gradient descent?

The short answer: the cost function is too complex to solve directly. Especially with this many weights and biases.

Nature of the Cost Function

- In a simple linear regression:

the cost function (squared error) is a convex quadratic.

- We can solve directly using linear algebra (normal equations).

- That gives exact weights in one shot.

-

In a neural network:

- Activations → nonlinear (sigmoid, ReLU, tanh).

- Layers stack → compositions of nonlinear functions.

- Cost function becomes a high-dimensional, non-convex surface with many valleys, ridges, and plateaus.

- No closed-form formula exists for the global minimizer.

So you can’t just “subtract directly” to jump to the answer.

How Gradient Descent saves the day

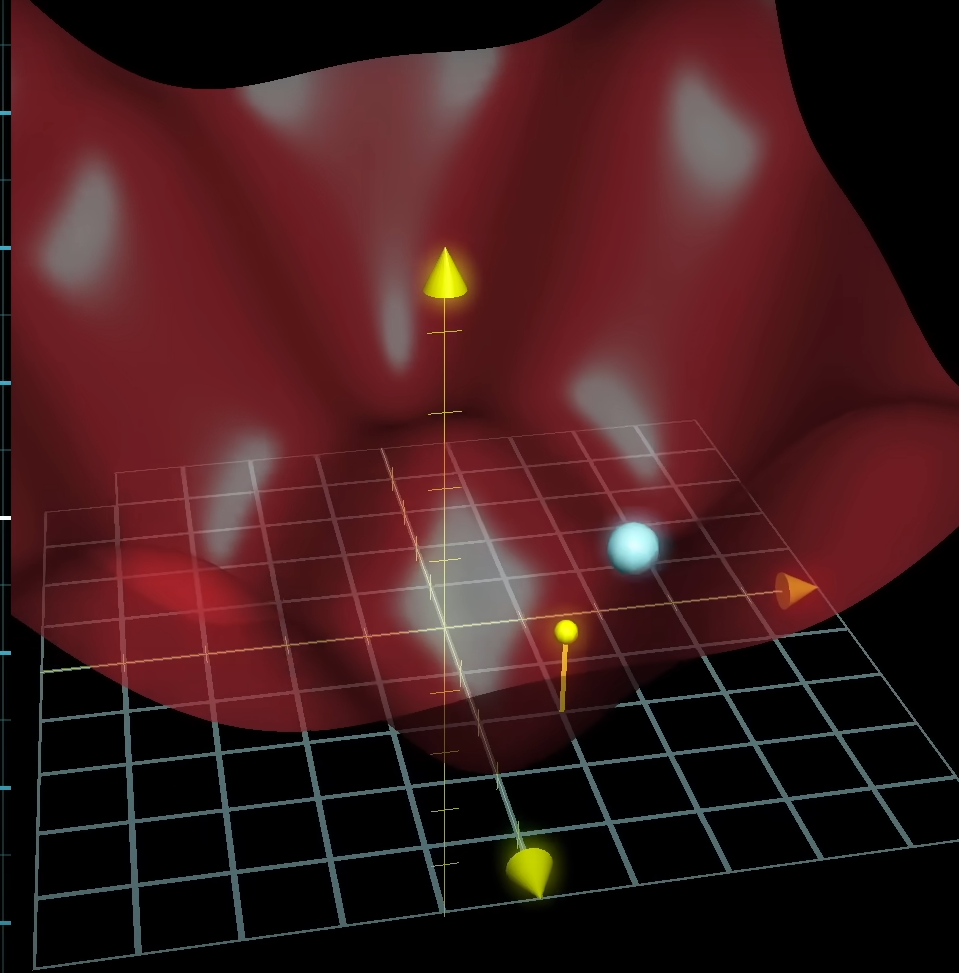

Now, this, is where gradient descent comes into play.

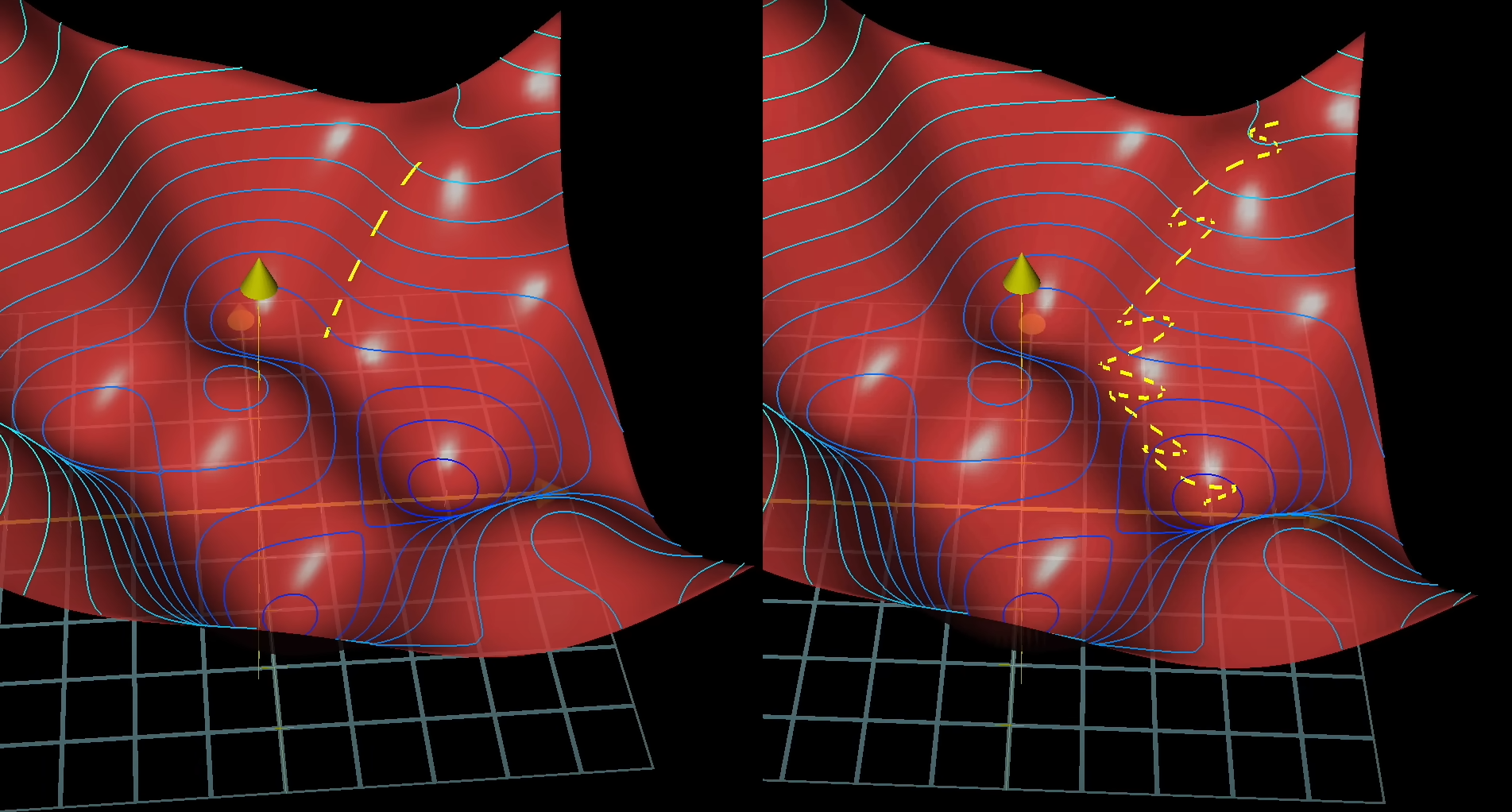

Think of gradient descent as feeling your way down a mountain with fog:

- You don’t know where the lowest point is.

- But the gradient tells you the steepest downhill direction at each step.

- By repeatedly stepping in that direction, you (hopefully) reach a low valley (local minimum, often good enough).

- Gradient-descent handles this in iterations, with the help of an algorithm called backpropagation (more on this in the next section.)

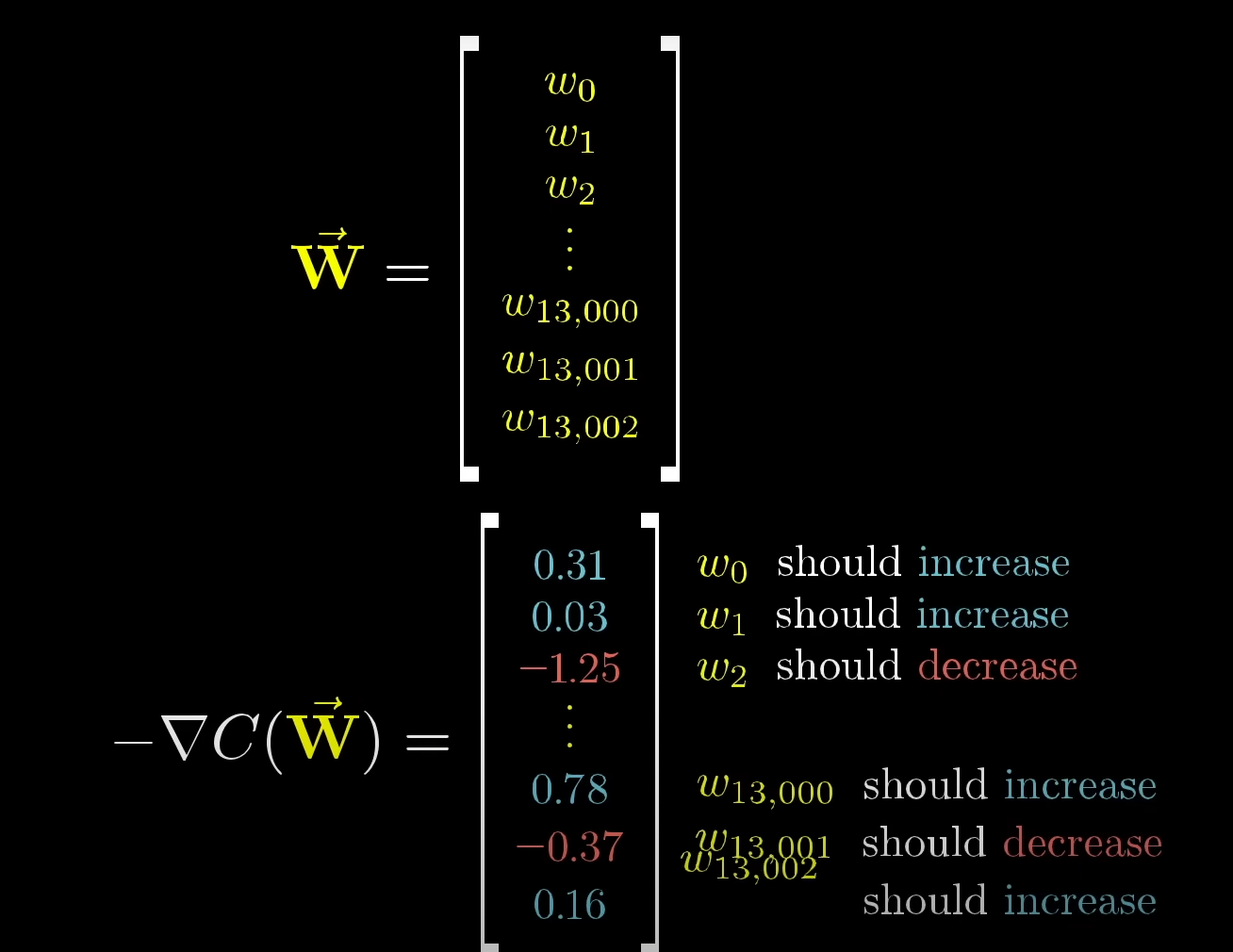

So, that's how, we eventually reach a vector matrix of weights and biases after the gradient descent, each of which when applied, tells us how to nudge the network towards the lowest possible activation value for that specific neuron. And not just that, to the reader, it also tells us very specific information as to

Suppose, we take this matrix right here:

The values of this cost matrix tells us something very precise about all the weights.

For example,

and so on...

This is represented in the network as strengthening of edges, meaning some edges will matter more, some will matter less, all pertaining to the path of finding patterns starting from the input layer for a specific combination of inputs and ending at the output layer, showing the desired output.

Tuning back: How might Sparse Modeling help us here?

Since the cost function is an amalgamation of (in this example),

What if we could somehow, optimize this by finding only the relevant weights and turning the unnecessary ones off? That would save us a lot of computation cycles in the gradient descent iterations.

That's where our sparse modeling kicks in, optimizing the cost function by using either the L1 or L2 norms to get us a sparse matrix by only finding the relevant weights and turning off the rest.

Backpropagation, the heart of learning in neural networks

Quick history about the backpropagation algorithm(skip if you just want to get into the algorithm itself only)

Now, Backpropagation was not theorized and published till 1986, so after Rosenblatt published his initial findings on the perceptron and tinkered around with it, work on the perceptron gradually slowed down and led to the the decades of the "AI winter", where most researchers moved on, due to significant problems with perceptron not being able to learn properly and the computation bottleneck faced with vast amount of weights and biases being tweaked manually in a network of multiple layers and a large dataset.

That's where Geoffrey Hinton came in. He is dubbed "The Godfather of deep learning". Hinton is recognized for his pivotal role in reviving neural network research and laying the groundwork for modern deep learning. He persisted in the field during the decades of the "AI winter," when most researchers had moved on.

In 1986, Hinton co-authored a highly influential paper that popularized the backpropagation algorithm, an efficient method for training multi-layered neural networks. While not his invention alone, this work demonstrated that deep networks could effectively learn.

His work on unsupervised learning with Restricted Boltzmann Machines and his collaboration on the AlexNet deep convolutional neural network in 2012 demonstrated that deep neural networks could achieve breakthroughs in image recognition and other tasks, launching the current AI boom.

Back to backpropagation

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ilg3gGewQ5U&list=PLZHQObOWTQDNU6R1_67000Dx_ZCJB-3pi&index=3

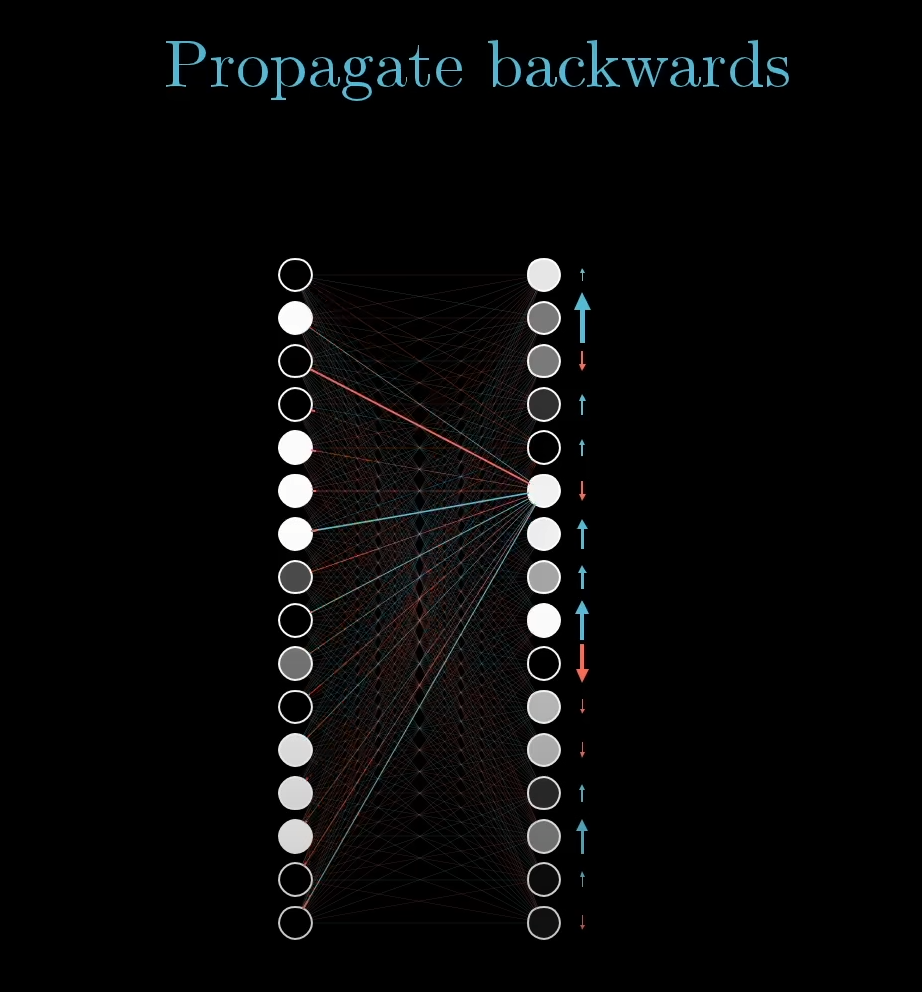

So, now that we can influence the weights and biases to get a certain pattern of activations, these can only reflect in the output layer if the previous layers' weights and biases are set accordingly.

But how do we start at the last layer and re-adjust the previous layers?

It's quite simple, once we calculate the gradient descent vector matrix containing the required weights and biases for the last layer to reflect the desired output for that neuron, we propagate those weights and biases backwards to the previous layer so that the last layer is affected.

Similarly, now that we know the desired weights and biases of the second last layer, we can again find the minimized cost function using gradient descent so that these desired values can be maintained in the second last layer, but applying the newly calculated weights and biases the layer before that, i.e. the third last layer.

Recursively we can keep on proceeding till we reach the second layer, i.e the layer after the input layer, thus successfully tweaking the weights and biases of the entire network.

Now, for computers, going along the traditional route and calculating the gradient descent for all the cost functions of the entire network layer by layer is extremely demanding and time consuming, since each calculation will use every single training example in the dataset, which can have potentially thousands of samples. So here's what's done in practice instead:

The training dataset is shuffled and split into mini-batches, each batch can have let's say a 100 samples. Now we compute the gradient descent over these mini batches instead. It's not going to be as accurate as the original method of going over the entire dataset, but it's going to give us a close up approximate of the cost function's minima, essentially, a local minima. However, the major advantage is the boost in training speed.

This is how both methods would look when plotted.

The image on the left is the true gradient descent over all of the training dataset at once while the right side is the result of training over mini-batches over iterations. The left one would look like a careful man taking a precise calculation and going downhill, while the right one is a drunk man descending randomly but much faster than the man on the left.

This method of gradient descent via backpropagation on mini-batches, is called the Stochastic Gradient Descent method.

The math behind backpropagation.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tIeHLnjs5U8&list=PLZHQObOWTQDNU6R1_67000Dx_ZCJB-3pi&index=4

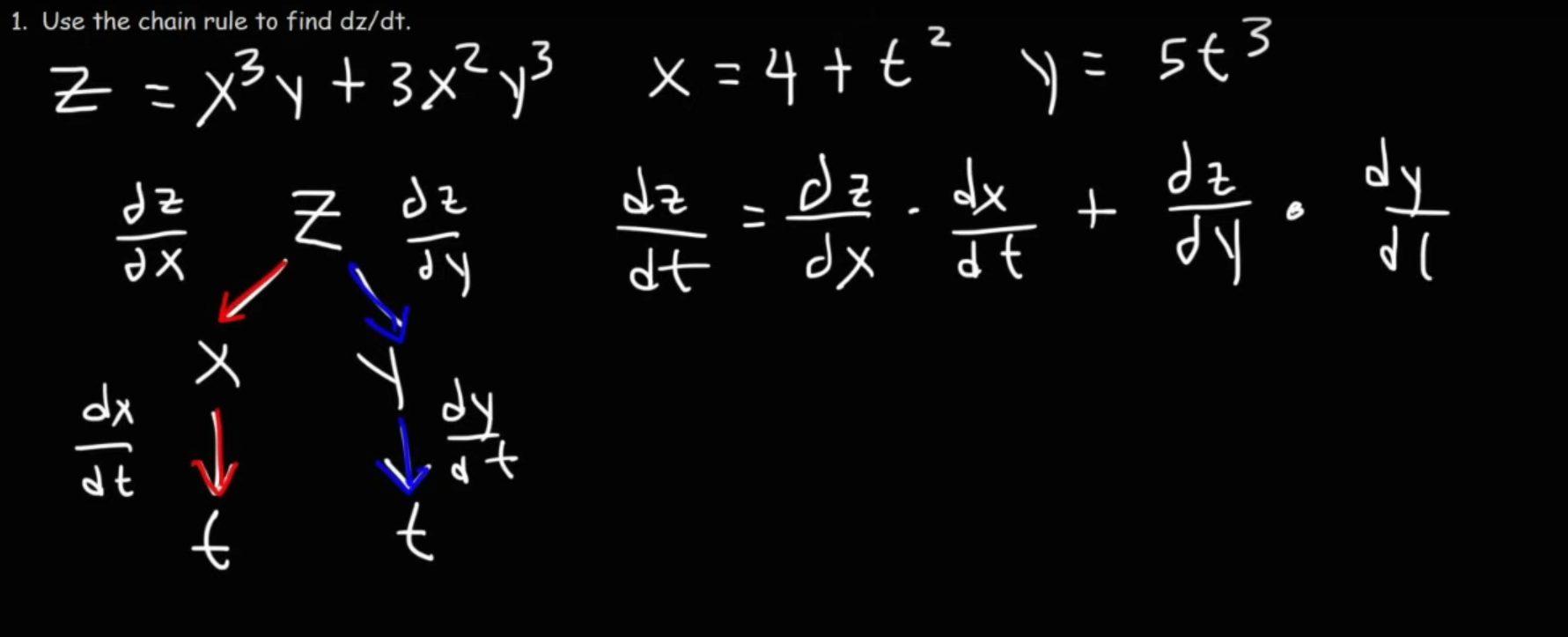

Pre-requisite: Multivariable differential calculus and the chain rule.

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLF-vWhgiaXWNi9OuPCbguaPgL67XH7crm

You can refer to this playlist for a quick recap of the multivariable calculus chain rule (TheOrganiChemistryTutor math)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XipB_uEexF0&list=PLF-vWhgiaXWNi9OuPCbguaPgL67XH7crm&index=3

A very simple method of solving a multivariable calculus equation via the chain rule is to draw a tree like this:

And once we have constructed the equation, we can then just perform standard differentiation rules to solve it.

Coming back to the math behind backpropagation

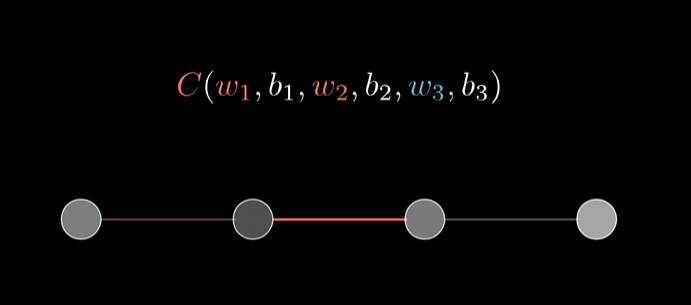

Let's lose the multi neurons per layer and fall back to a simple model where there is only one neuron per layer.

Here we have a simple network of 4 layers, the input layer, two hidden layers and the output layer, each having only one neuron.

The

Let's give some notations.

is the desired activation, is the predicted activation value of the output layer, let's say is the predicted activation value of the second last layer, let's say .

The cost function of the last layer is the square of the difference between the predicted and the desired activations.

and the activation is:

We can set

So,

which contains the activation of the previous layer.

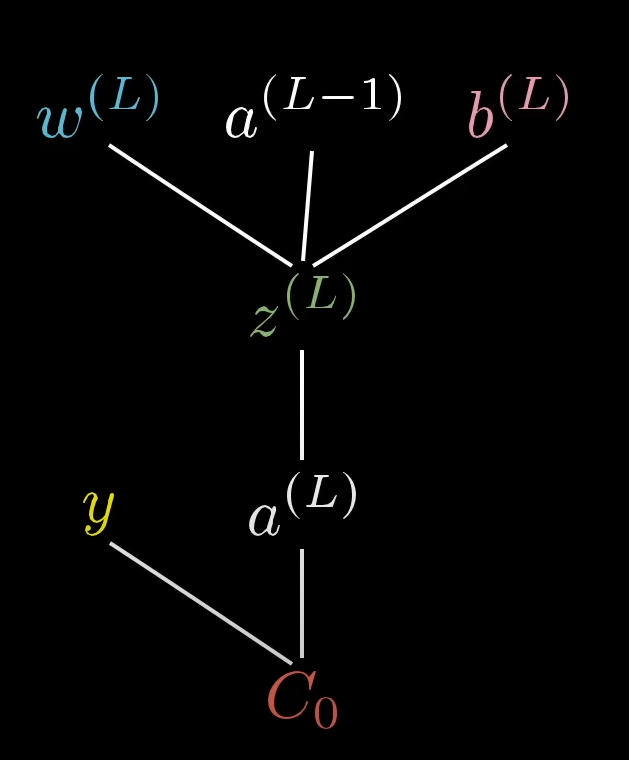

Now, we can visualize the dependency tree as follows:

graph TD; w_l --> z_l; a_l-1 --> z_l; b_l --> z_l; z_l --> a_l; y --> C_0; a_l --> C_0;

or, for a better depiction:

Now, we can use this dependency tree to answer some questions like:

How does the weight of the last neuron affect the cost function?

How does the bias of the last neuron affect the cost function?

For that we need to find two derivatives, or the rate of change of the cost function w.r.t both the weight and the bias separately:

Based on that, we get two equations:

first part says : How does z(the weighted sum) depend on the weight itself?

second part says: How does the activation depend on the weighted sum?

third part says: How does the cost function depend on the activation?

Put them together and we get the rate of change of the cost function w.r.t the weight.

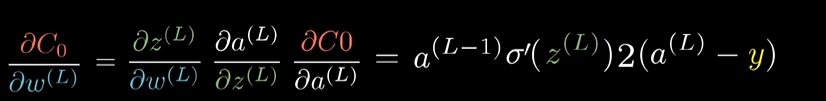

Solving it, we get:

Now, similarly, for the bias:

Only the first part changes, which says: How does the weighted sum depend on the bias this time?, while the rest of the parts remain the same.

Put them together and we get the rate of change of the cost function w.r.t the bias.

Put these two together and we get how the cost function of the current layer depends on both the weight and bias of the previous layer, and thus what values to propagate backwards to the previous layer.

Now, falling back to our true neural network example, the rate of change of the cost function w.r.t the weight would be:

which is the derivative over the average of all training examples, per mini-batch.

Similarly, for the bias:

So, our final cost matrix will be:

And that concludes, how backpropagation, the heart of learning in neural networks, works on the math side.

Neural Networks: Large Language Models

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LPZh9BOjkQs&list=PLZHQObOWTQDNU6R1_67000Dx_ZCJB-3pi&index=5 (You must watch this video as the most of the concept can only be understood with visual animations, which I can't very much, properly complement with my simple text.)

Now we delve under the hood of the most widely used and the main factor behind the AI boom, the Large Language Model.

Building on our knowledge of the humble perceptron and how it works, how it learns via backpropagation, large language models introduce some new tech to the table.

The Core Idea of an LLM

Think of a standard LLM like a highly advanced, super-powered autocomplete. Its single, simple goal is to predict the most likely next word in a sentence. When you interact with a chatbot, it's doing this over and over, one word at a time, to build a full response. What makes it so eerily good at this is the scale and the architecture.

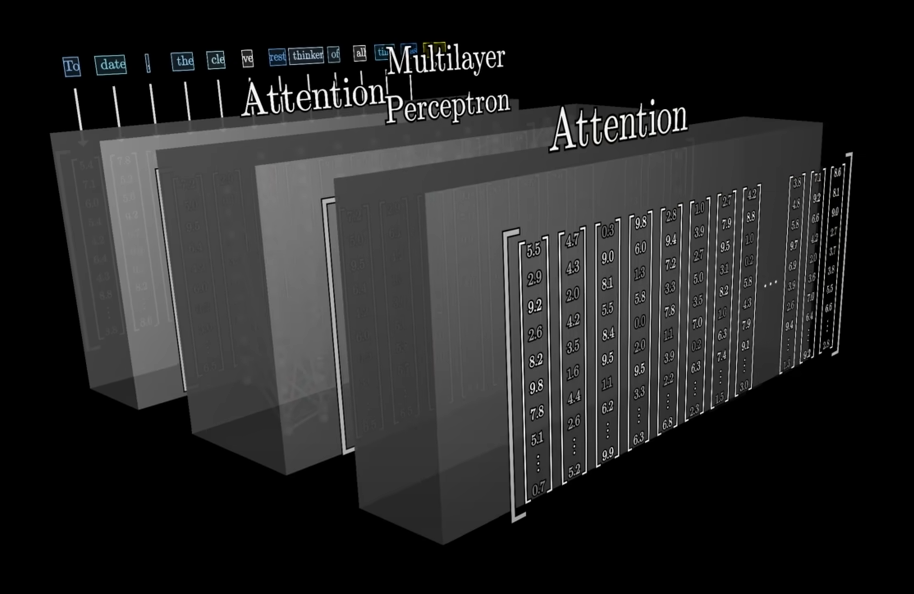

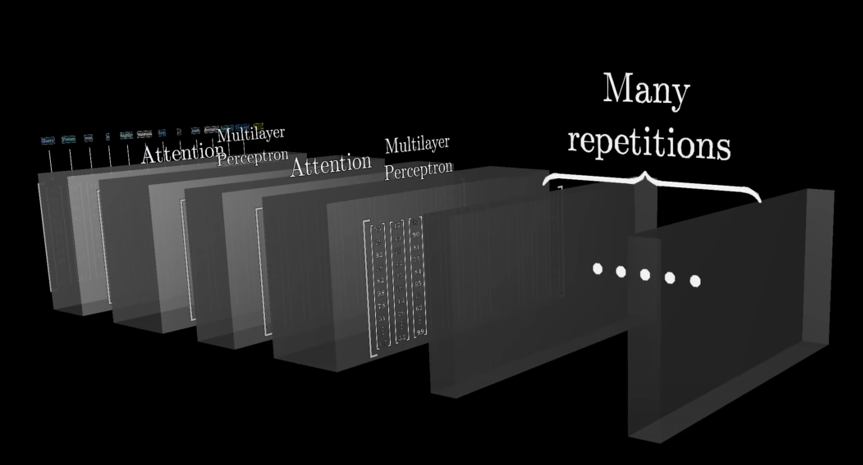

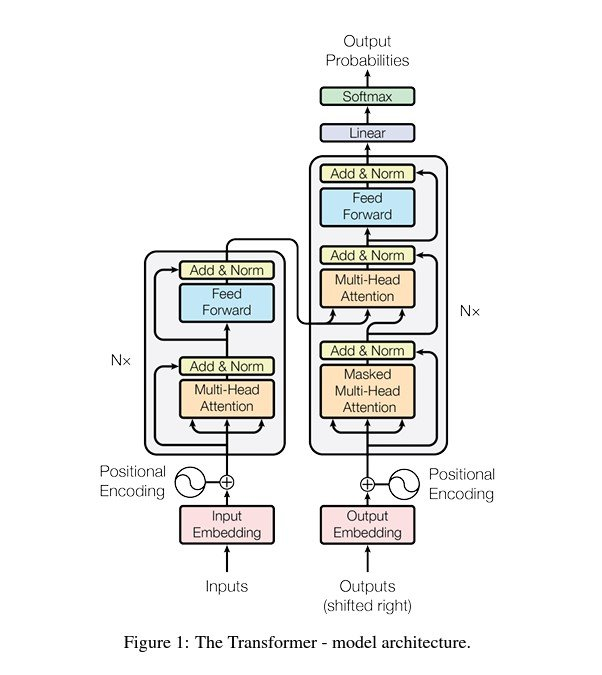

1. The Transformer: The New Neural Network Architecture

Remember how our simple neural network processed data in layers? Well, old-school language models had to process text one word at a time, which was slow and hard to keep track of long sentences.

Then came the Transformer. This new architecture was a revolution! Instead of processing words sequentially, it soaks in the entire input text all at once, in parallel. This makes it incredibly efficient and allows it to "see" the entire context simultaneously.

2. Word Embeddings: Giving Words Meaning

You know how a neuron takes in numerical values? LLMs do the same. First, every word (or even a part of a word) is converted into a list of numbers called a vector. This isn't just a random assignment; this vector actually encodes the word's meaning based on how it's used in the training data.

How the transformer does that, is covered in the detail in the next section.

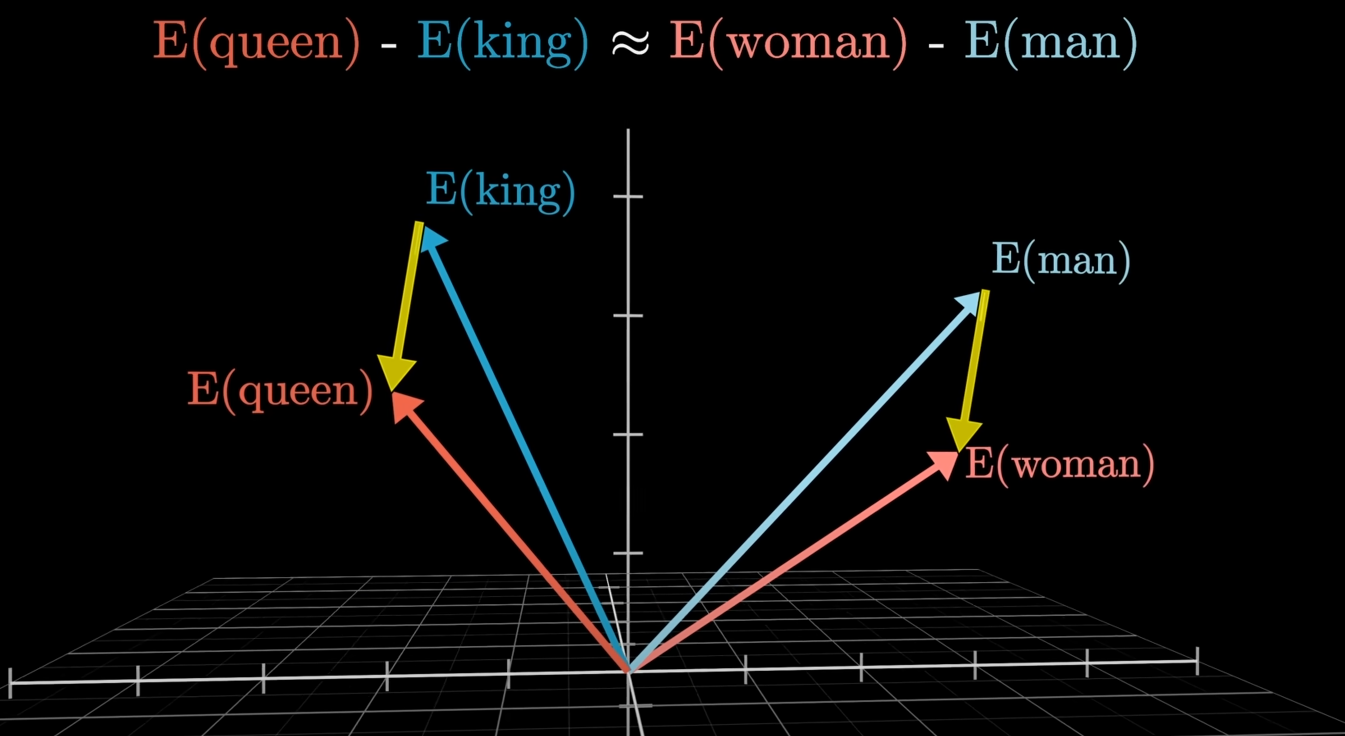

Words with similar meanings will have similar vectors. For example, the vectors for "king" and "queen" will be very close in this mathematical space, while the vector for "bicycle" will be far away. This gives the model a deeper understanding of language beyond just the words themselves.

3. The Attention Mechanism: The Secret Sauce

This is the true genius of the Transformer. The attention mechanism lets the model focus on the most important words in the input text when it's trying to predict the next word. It's like having a superpower that allows the model to instantly see how every word relates to every other word.

This superpower works with the help of something called a vector dot product and measuring the angle between two vectors to detect their similarities, and then turning it into a probability distribution by something called a "softmax" function (more on this in the next section).

For example, in the sentence, "The river bank was flooded," the attention mechanism would help the model know that "bank" is related to "river," not to money. This ability to instantly connect and weigh the relevance of words is why LLMs can handle context so well.

4. The Two-Step Training Process

LLMs don't just learn in one go; they go through a two-part training process:

-

Pre-training: This is where the model is fed an absolutely mind-boggling amount of text from the internet. We're talking trillions of words here. Its only job is to learn to predict the next word. This is where it soaks up all the patterns, grammar, and general knowledge of human language.

-

Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF): After pre-training, the model is still a bit raw. It might say unhelpful or even problematic things. This is where humans come in! Workers give the model feedback on its responses, and this feedback is used to fine-tune the model's parameters. This second phase is what turns a highly-skilled word predictor into a useful and safe assistant.

More on reinforcement learning in the next module.

Large Language Models : How Transformers work.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wjZofJX0v4M&list=PLZHQObOWTQDNU6R1_67000Dx_ZCJB-3pi&index=8 (must watch)

Alright, let's dive into the guts of the Transformer architecture, the engine that powers LLMs. Remember how we talked about neural networks having layers and parameters (weights and biases)? The Transformer is a specific, brilliant kind of neural network that organizes those parameters in a way that's perfect for handling language.

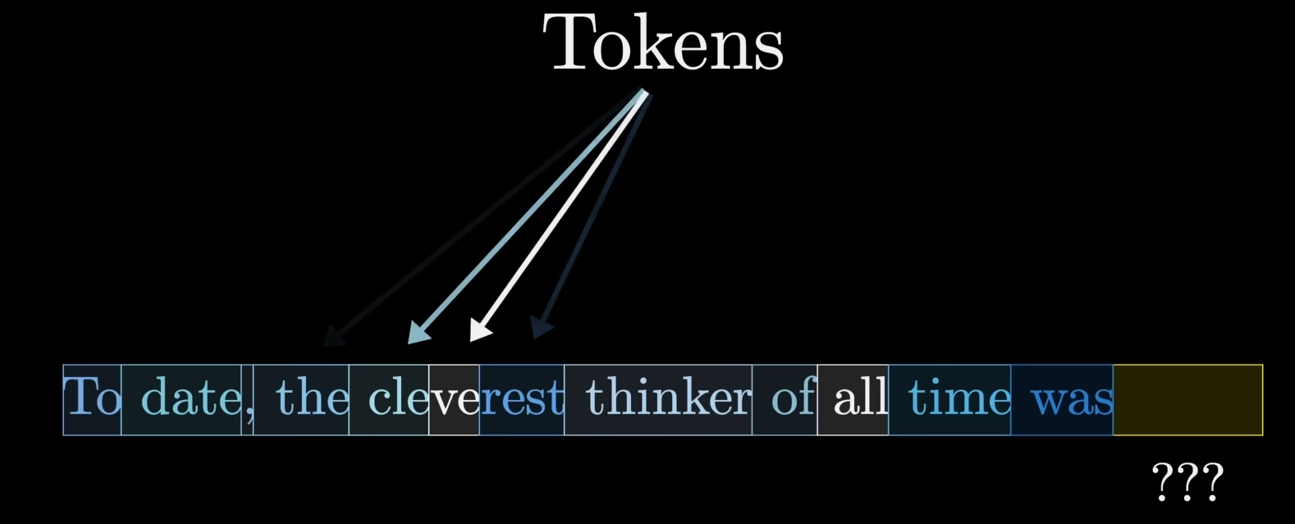

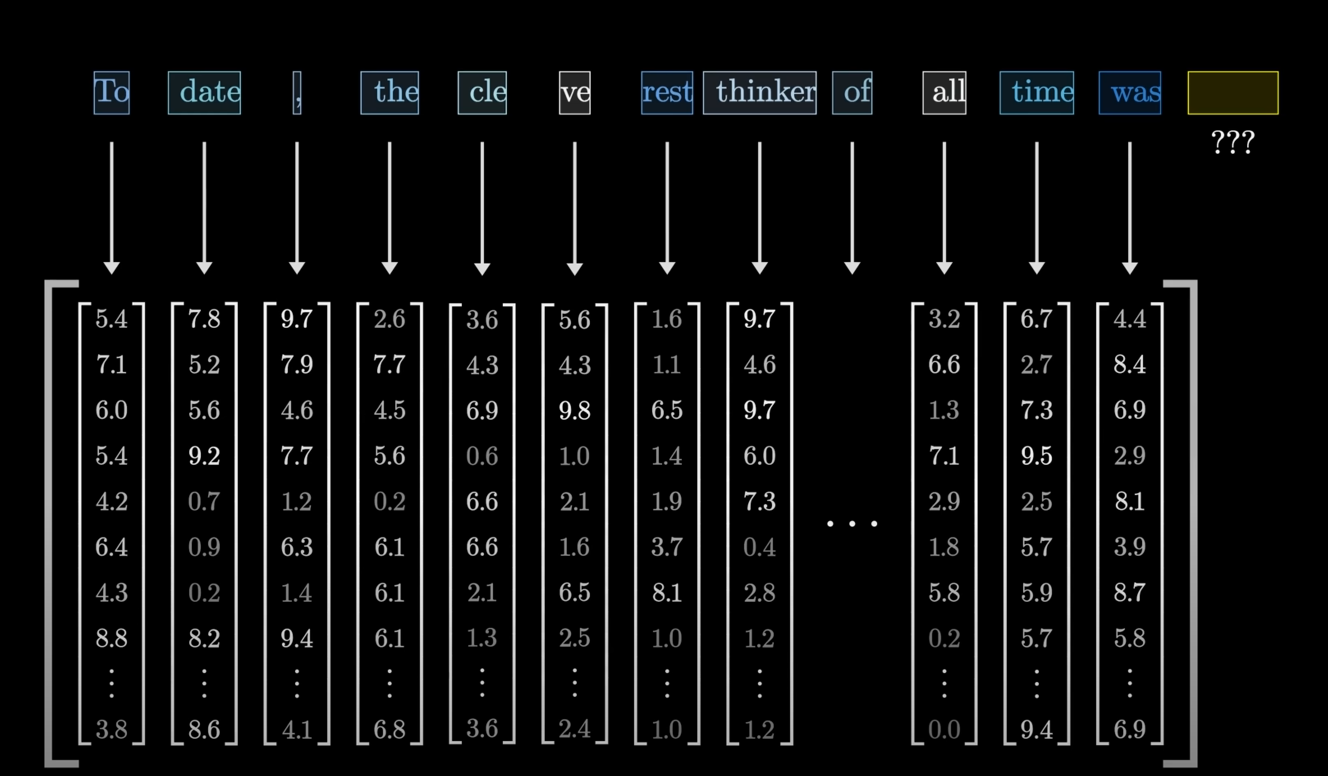

Step 1: Tokenization

The very first thing a Transformer does is turn the input text into a format it can understand: numbers. It doesn't just treat words as single units. The input is broken up into tiny chunks called tokens. These can be whole words, parts of words, or even punctuation.

For example, the word "unbelievable" could be broken down into the tokens ["un", "believ", "able"]. This approach helps manage a huge vocabulary and allows the model to handle words it's never seen before by combining existing tokens.

We also learnt about tokenization back in Module 2 -- Lexical Analysis#2. *Token Generation from compiler design. This is the same tokenization but a bit more focused on not taking every single word / number / symbol as a single token, and as much as that would help us to understand tokenization in Transformers easier, but in reality the tokenization in Transformers cut even deeper sometimes taking even subparts of a word or small character sequences from a part of a word as tokens as well.

If images or sounds are input, then the tokens can be like this: Small defined pixel by pixel parts of an image or small waveforms in case of a sound.

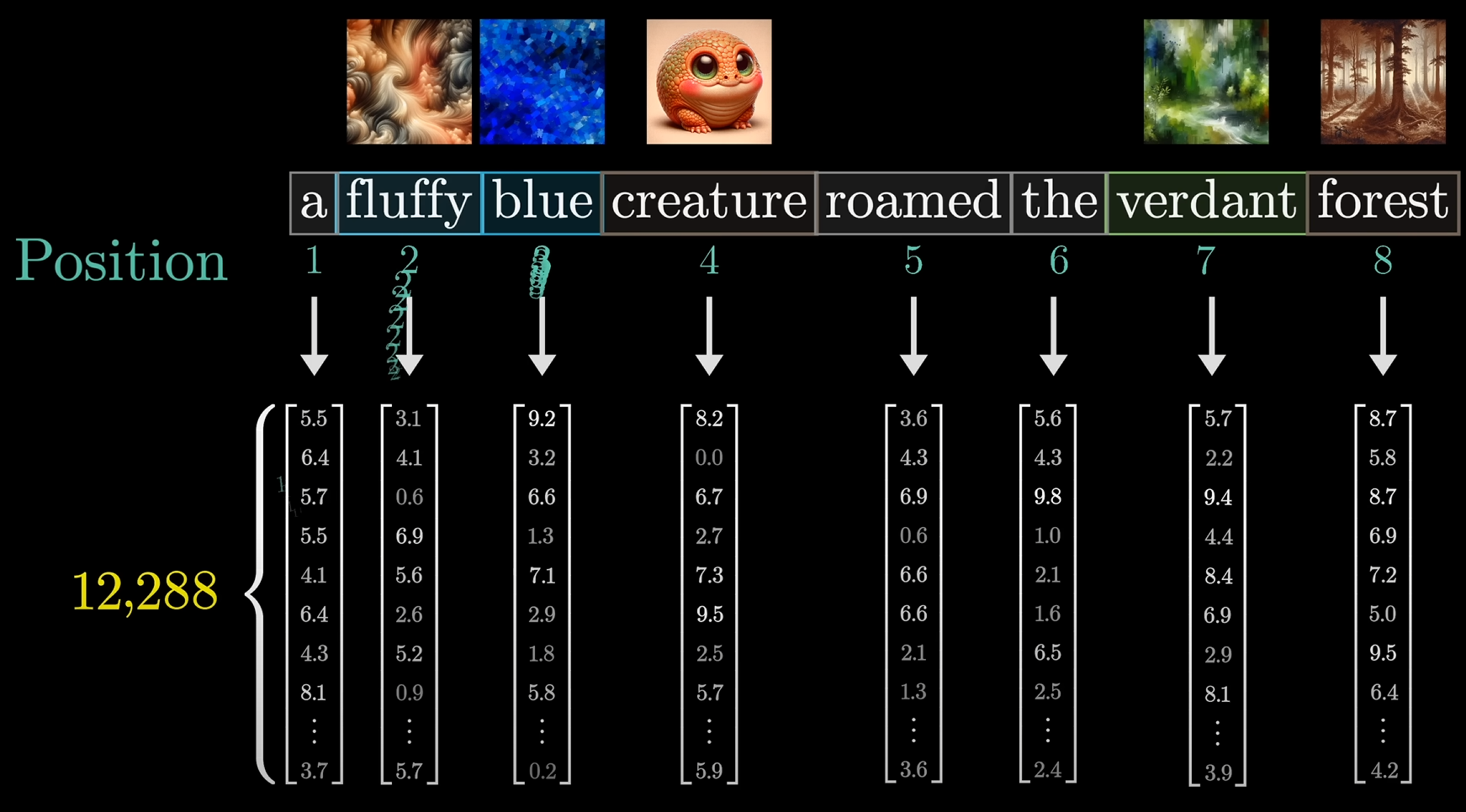

Step 2: The Embedding Matrix: From Words to Vectors

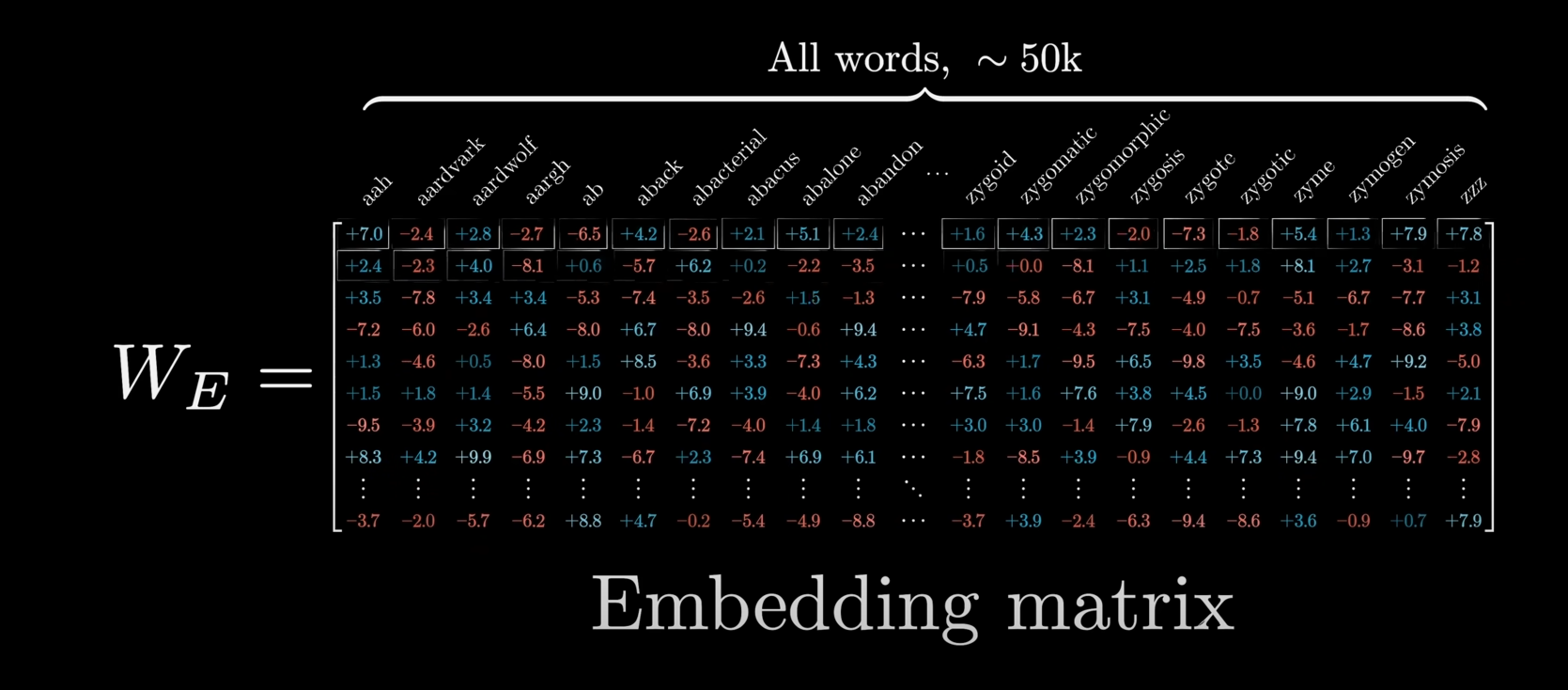

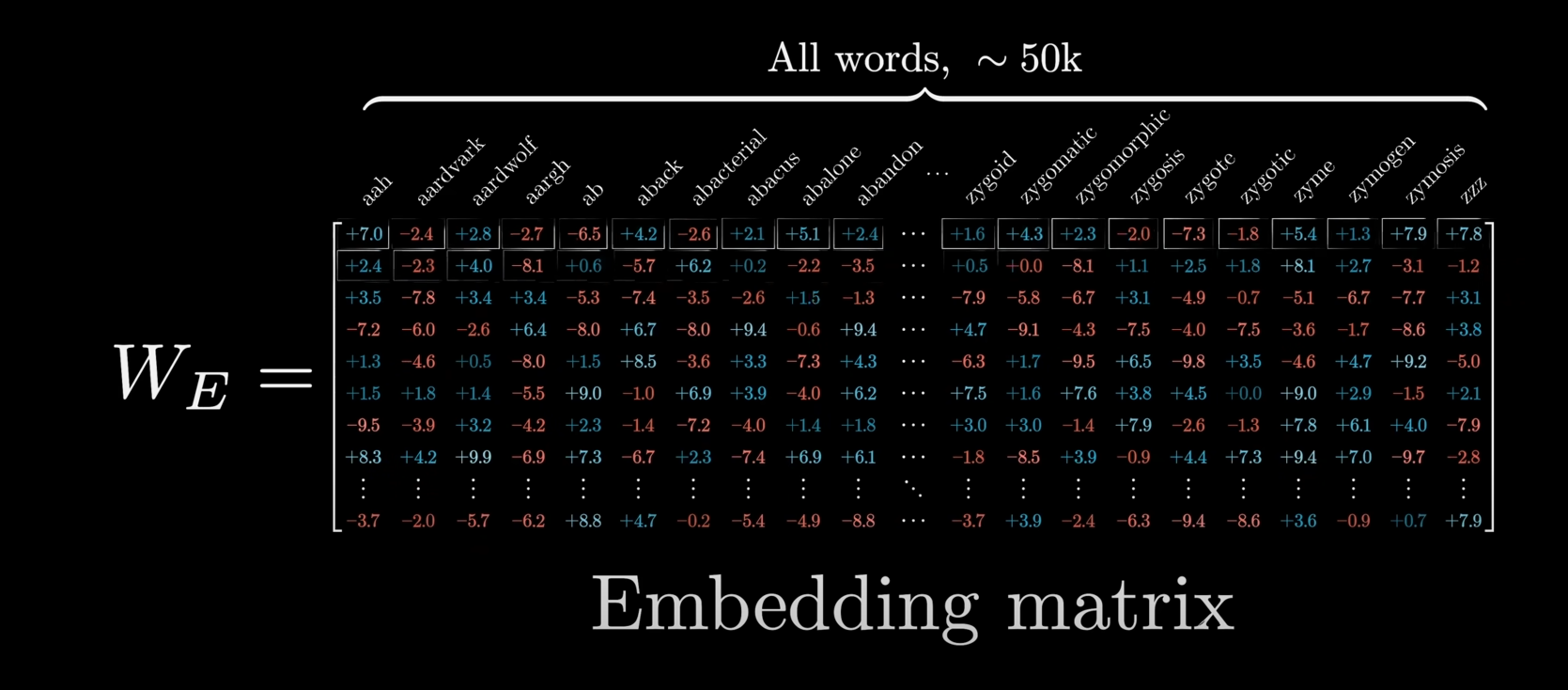

This step is where our tokens become the numerical inputs for the network. The model has a giant internal list of every possible token, which we can think of as a huge matrix called the embedding matrix (

Each column of this matrix is a vector—a list of numbers—that represents a token. When you feed a token into the model, it simply looks up its corresponding vector in this matrix. These vectors are what actually get processed by the rest of the network.

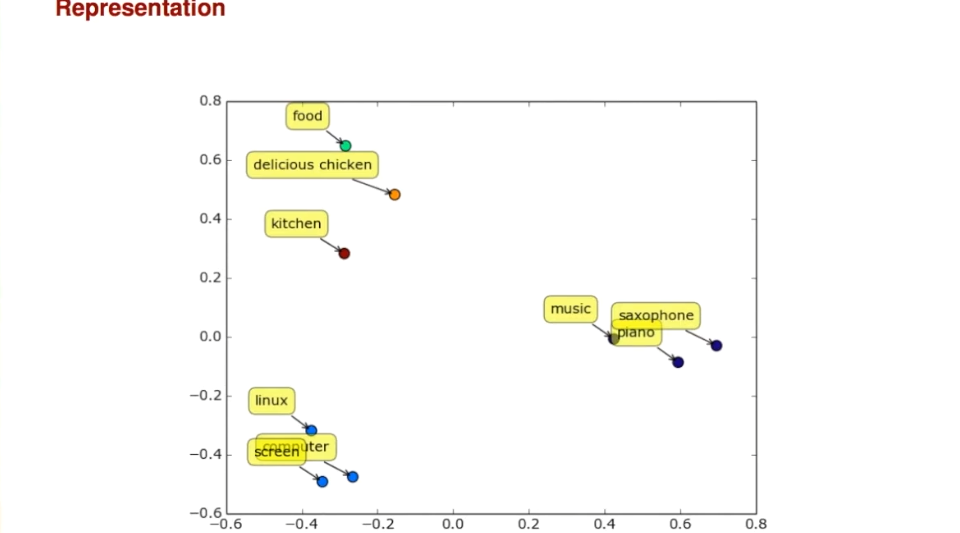

The cool part is that during training, the values in this matrix are tuned so that tokens with similar meanings end up with vectors that are close to each other in a high-dimensional space. For example, the vector for "queen" might be very close to the vector for "king."

Also, the number of entries allowed in the embedding matrix is also known as the "context window" of the LLM. This context window is basically the amount of information that the LLM can actively process as defined within the boundaries of the embedding matrix. Earlier versions of ChatGPT, GPT-3, didn't have that much of a higher context window and thus would often lose information or the "context", when conversations got too large.

While running open source models, we can definitely tweak the context window and expand it, and doing so the model will be able to process more context and attention, but that will result in a higher computation load on the system.

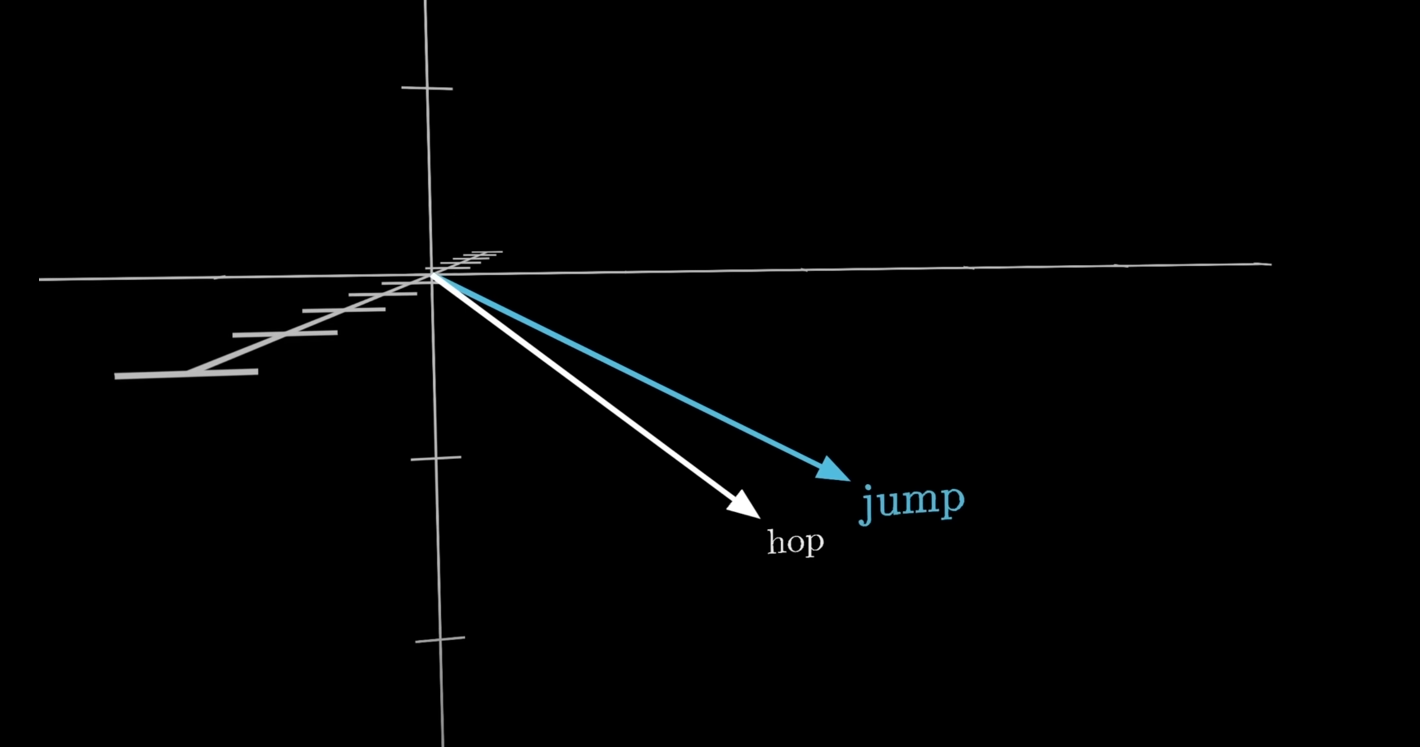

For example, in this image, take a look at how close the vectors of the words hop and jump are:

If we were to perform a simple cosine similarity distance search (Module 3 -- Time Series Mining#3. Cosine Similarity Search) the angles between the two vectors would be very close to

Knowing the angle and relation between two different word vectors can also help in predicting if another word vector of either type is available.

For example, take relation and angle between two words, man and woman. Now since we know the relation and angle between them, if we tried predicting which world would be the most commonly said after the word "king", it turns out to be "queen", but just taking the angle between the words "man" and "woman", we can use that angle to predict the word for "king" to be "queen".

Step 3: The Attention Block: Vectors Talking to Each Other

This is the heart of the Transformer. The attention block is an operation that allows all the vectors (representing the tokens in the input) to "talk" to each other. The goal is for each token's vector to be updated with information from the rest of the text.

Think back to our "river bank" example. The vector for the token "bank" would receive information from the vector for "river," which would change its value to encode the meaning of a riverbank, not a financial bank. This happens for every vector in the sequence, all in parallel, which is what makes it so fast and effective at understanding context.

How does it decide what to pay "attention" to? It uses the dot product of the vectors. The dot product is a way to measure how well two vectors are aligned.(Basically cosine similarity in short.) A large, positive dot product means the vectors point in similar directions, indicating a strong relationship. The attention mechanism uses these dot products to determine how much influence each vector has on the others.

Step 4: The Feed-Forward Layer

After the attention block, the vectors pass through a feed-forward layer, also known as a multi-layer perceptron. In this step, the vectors don't talk to each other; they're each processed independently.

This layer is essentially a standard neural network that applies non-linear transformations and gives the model extra capacity to learn and store patterns from the training data.

Step 5: The Unembedding Matrix and the SoftMax function.

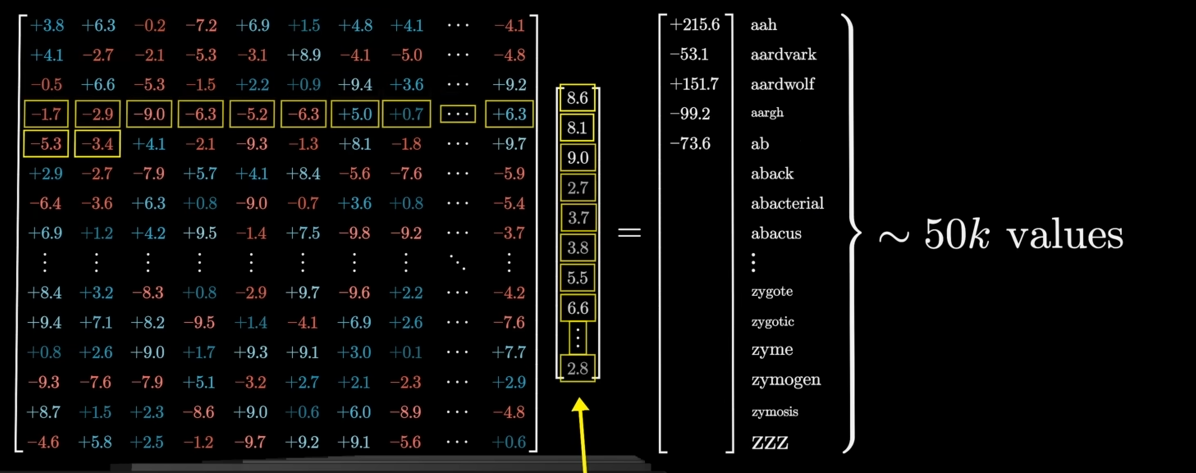

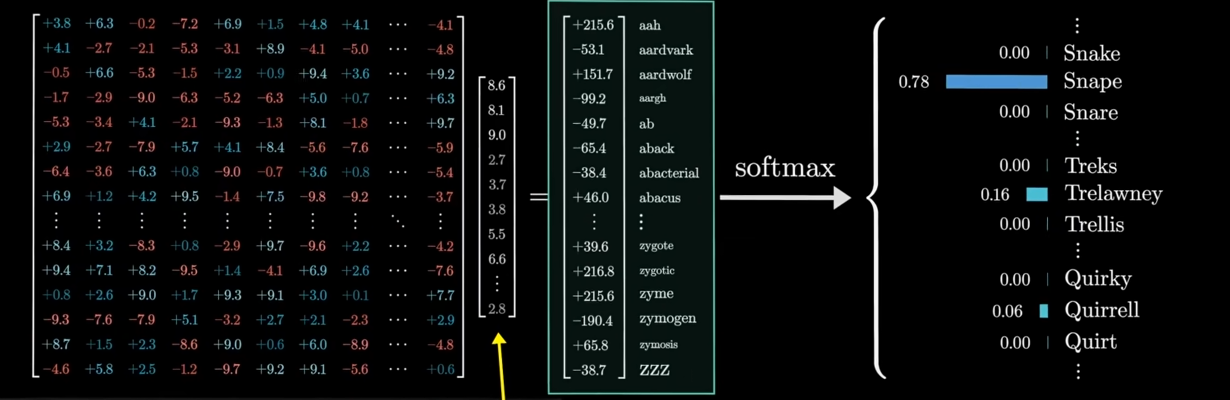

The final vector in the sequence, which has now been enriched with the context of the entire input, is used to make a prediction. This vector is multiplied by another massive matrix called the unembedding matrix (

This matrix is essentially the reverse of the embedding matrix. It translates the final vector back into a list of numbers, one for each token in the vocabulary. This raw output is often called the logits.

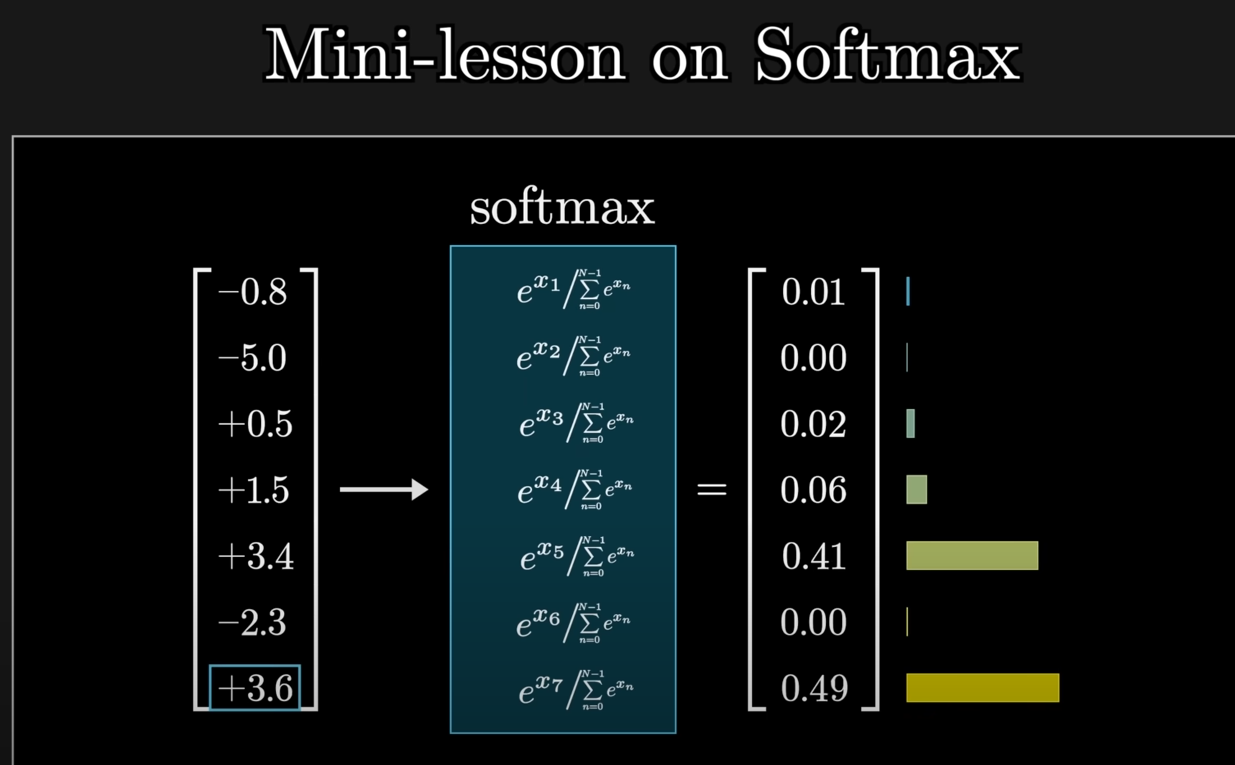

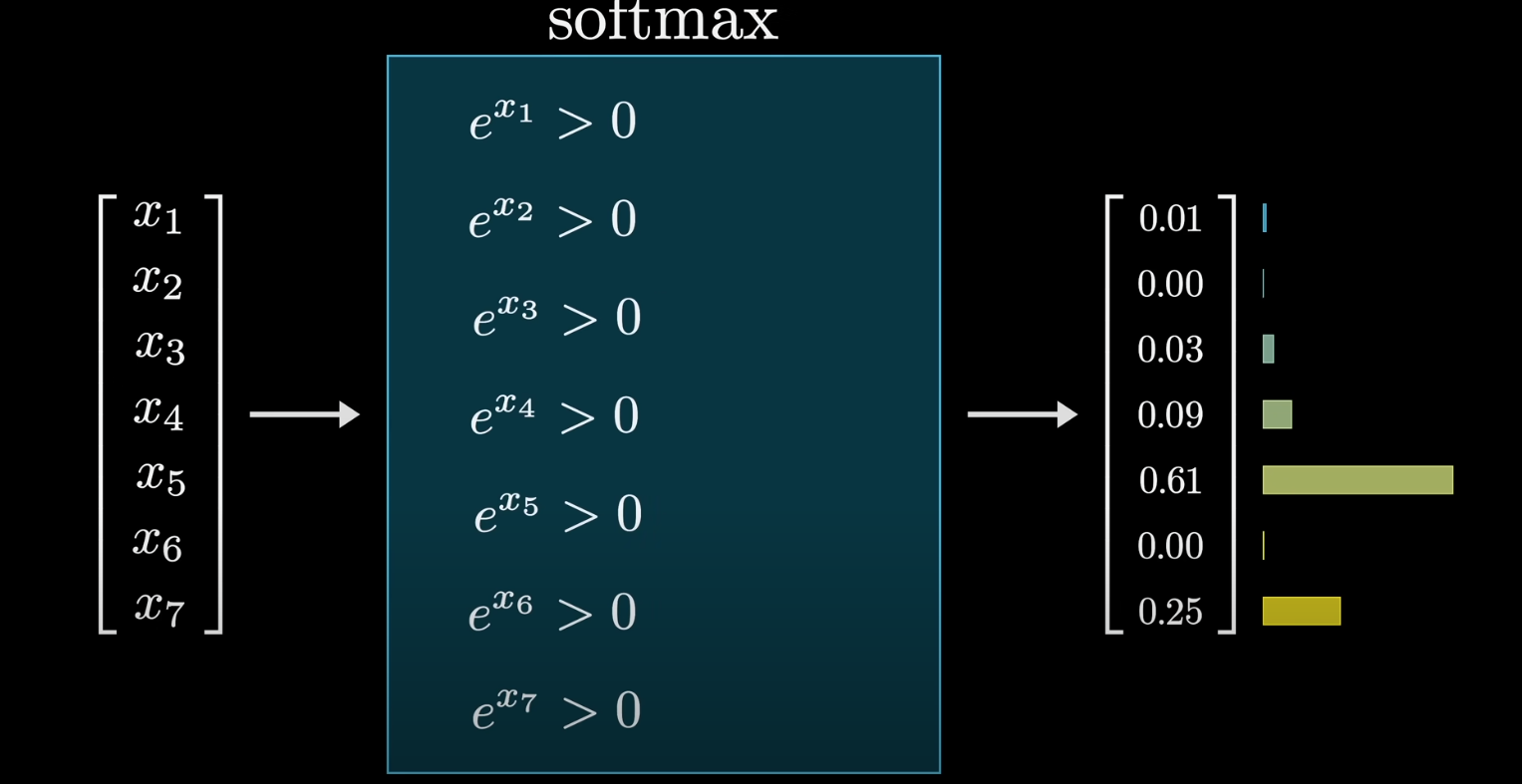

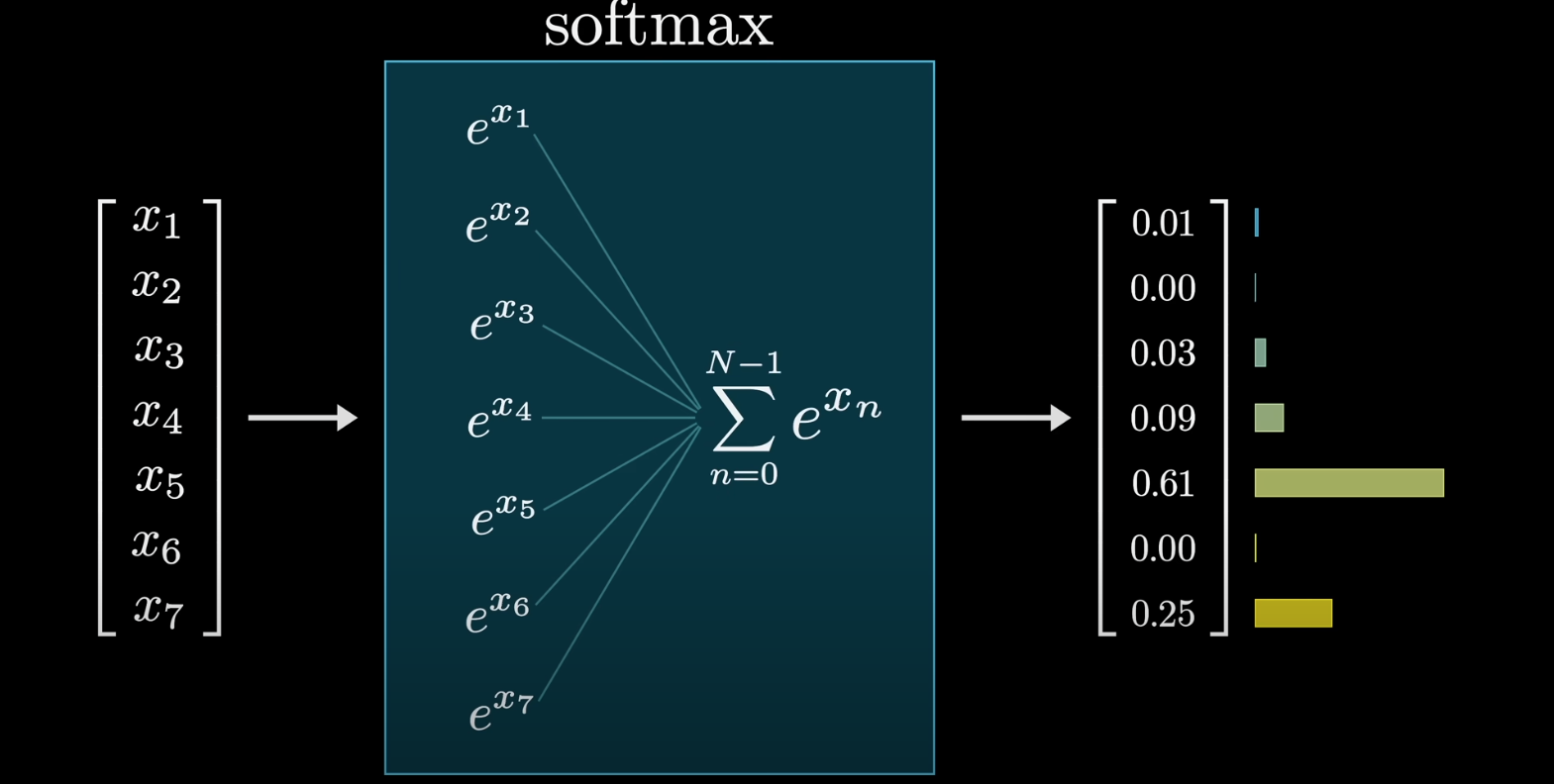

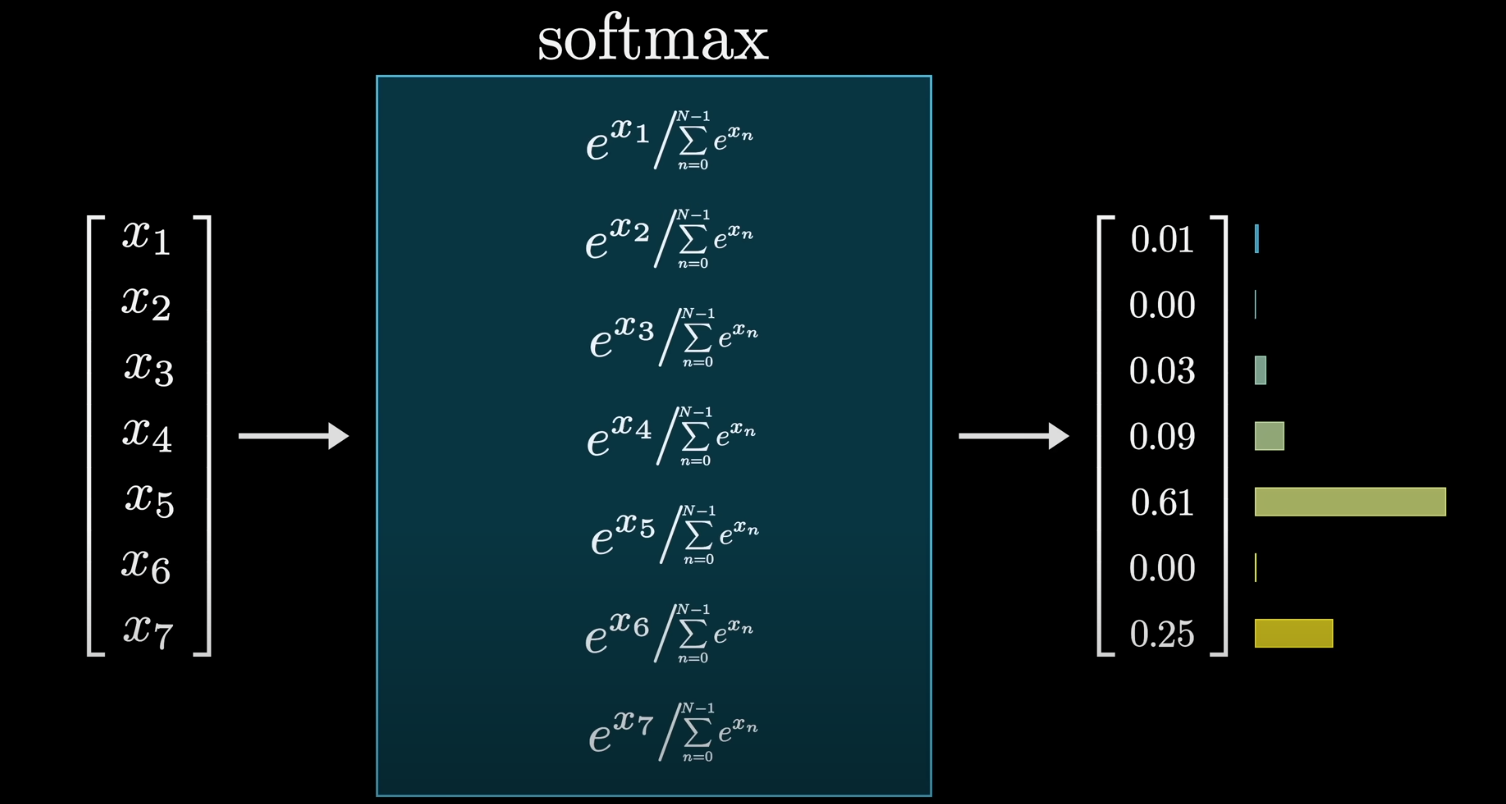

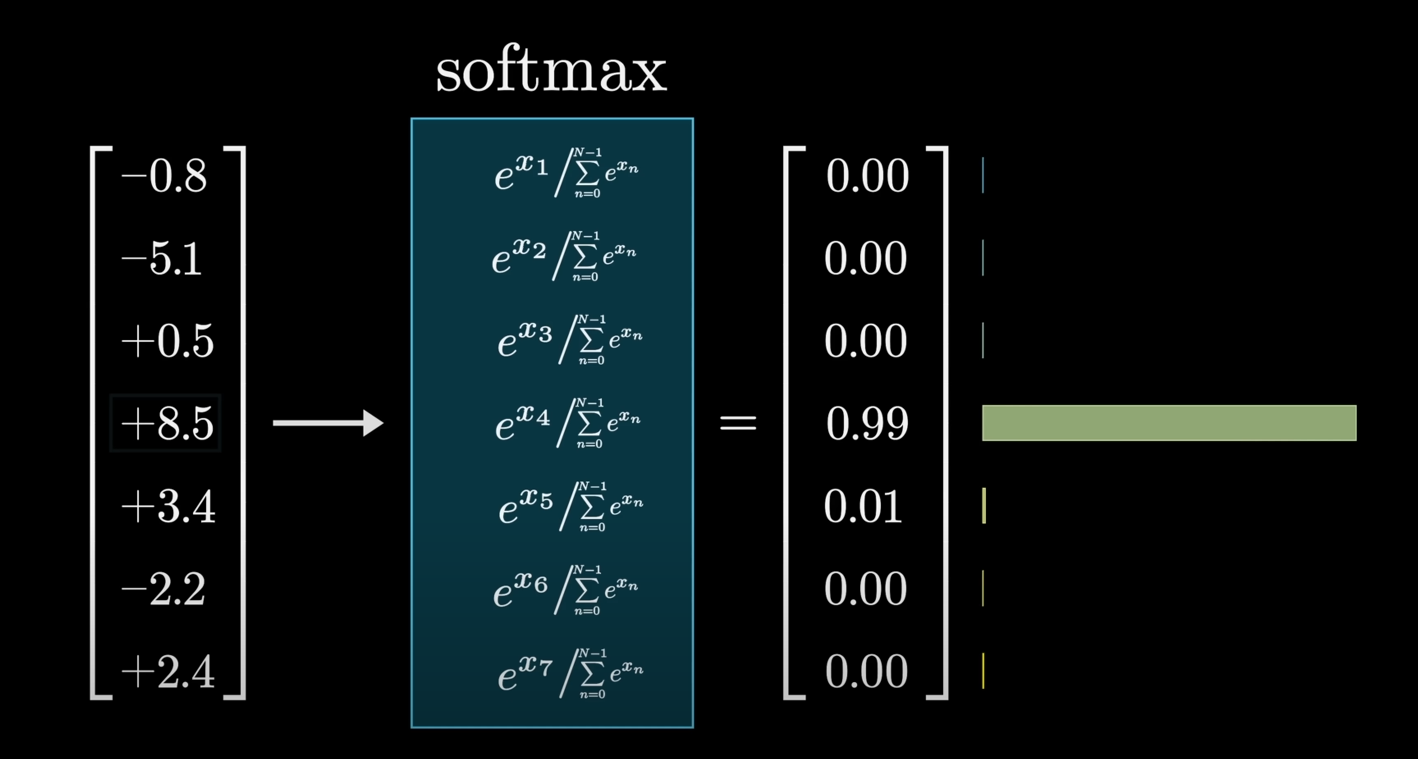

The final piece of the puzzle is the Softmax function. The logits are just a list of numbers and can be negative or larger than one. The Softmax function takes this list and converts it into a valid probability distribution, where every value is between 0 and 1, and they all add up to 1. The largest logit will correspond to the token with the highest probability.

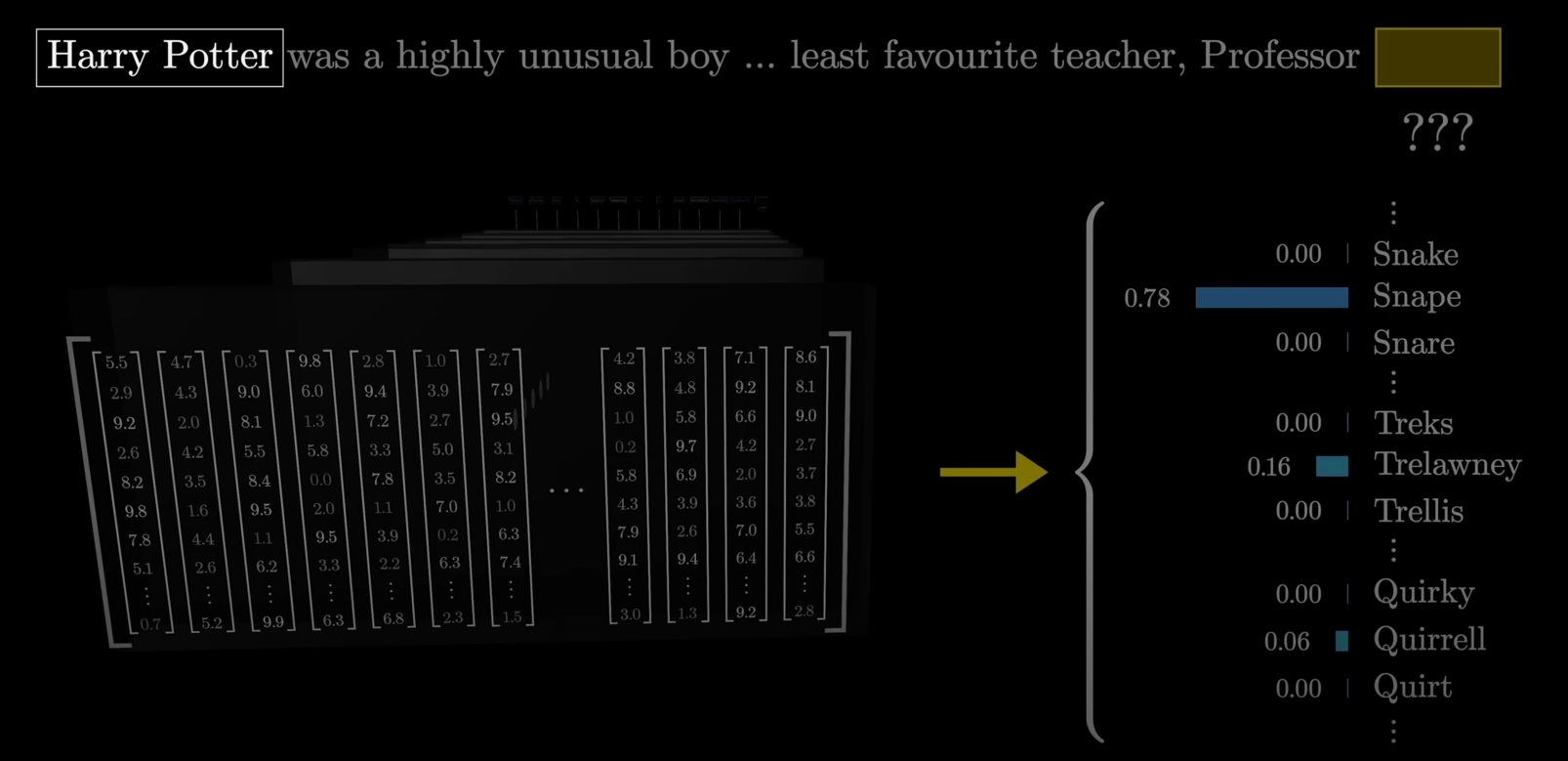

For example, take this example sentence which warrants a prediction:

"Harry Potter was a highly unusual boy .... least favourite teacher, Professor ???"

Generally we would expect the final output to be a set of probabilities, called a probability distribution of words like this:

And as you can see, the one with the highest probability, Snape (Serverus Snape) was indeed Harry's least favourite teacher.

These probability values need to be clamped between 0 and 1.

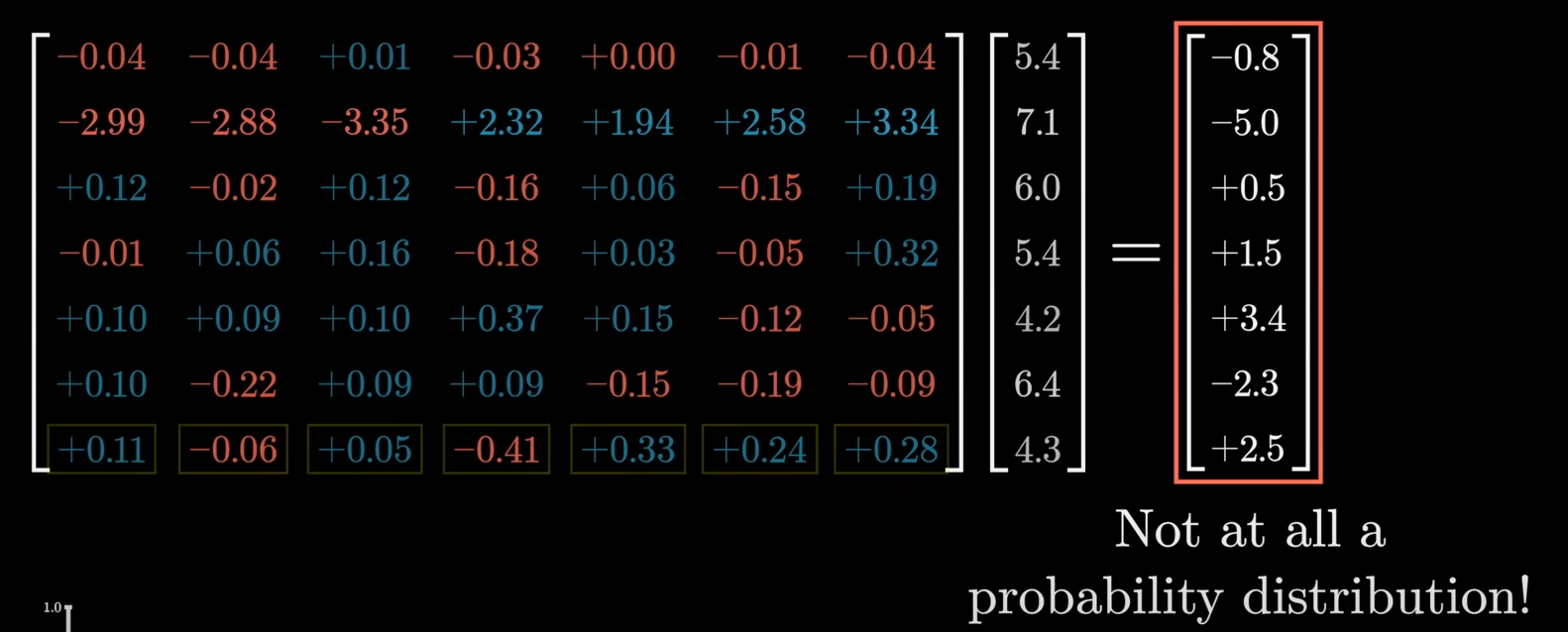

However, the unembedding matrix is basically a full blown matrix of different values for each original token, which often are not contained between 0 and 1, sometimes even negative numbers or even much bigger positive numbers:

So, how does one clamp these distributions between 0 and 1?

That's where the softmax function comes into play.

The SoftMax function directly converts the very high or very low, positive/negative values into probability distributions clamped between 0 and 1.

The formula for the SoftMax function is this:

Is we take one of the individual values as we are iterating through the matrix, let's say -0.8

We raise that to the power of

Then we take the sum of all these positive values:

And lastly, we divide each term by that sum:

The end result? A list of normalized positive values between 0 and 1.

That's how the SoftMax function works.

So, as you can see, if there was a value of

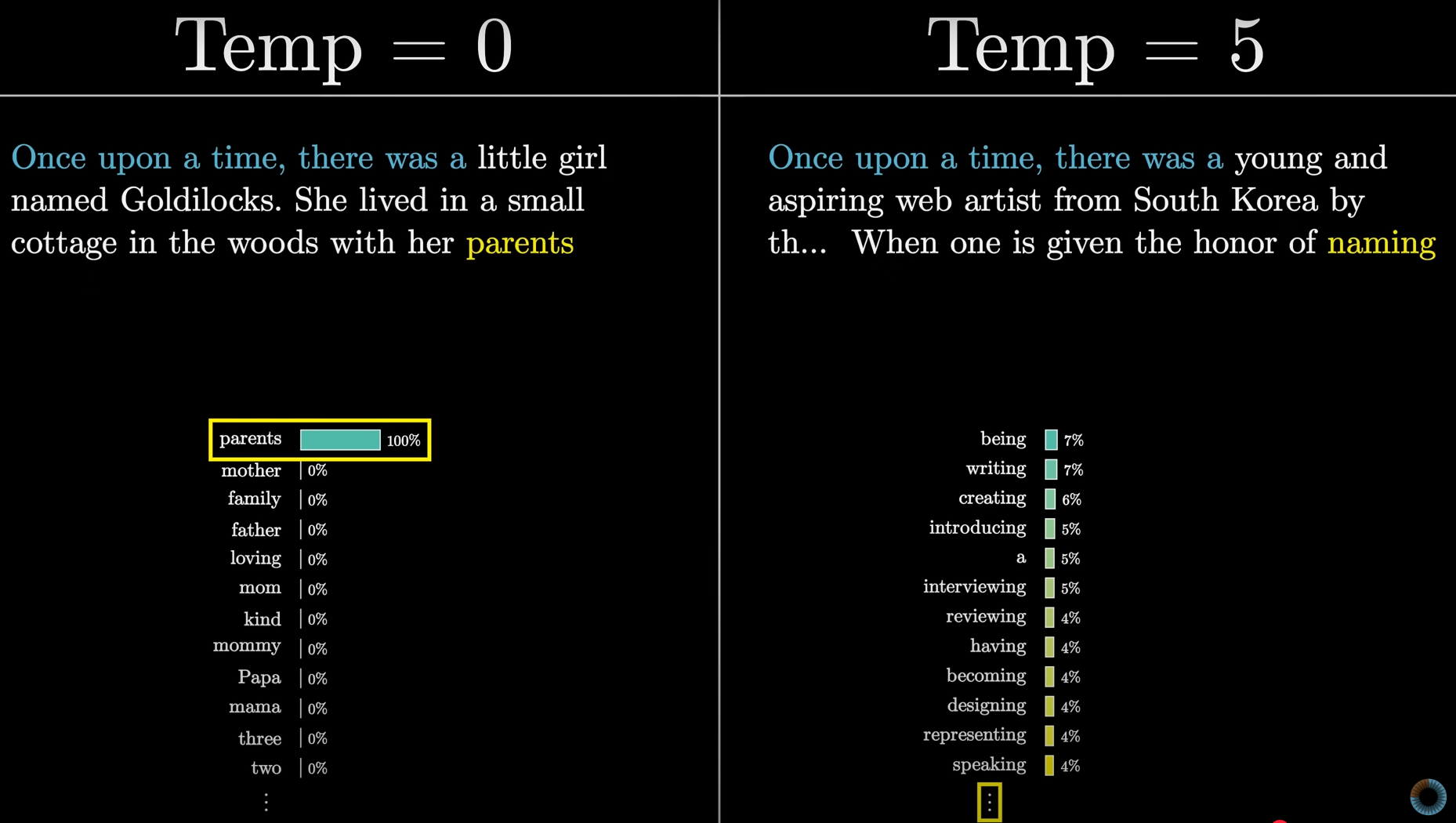

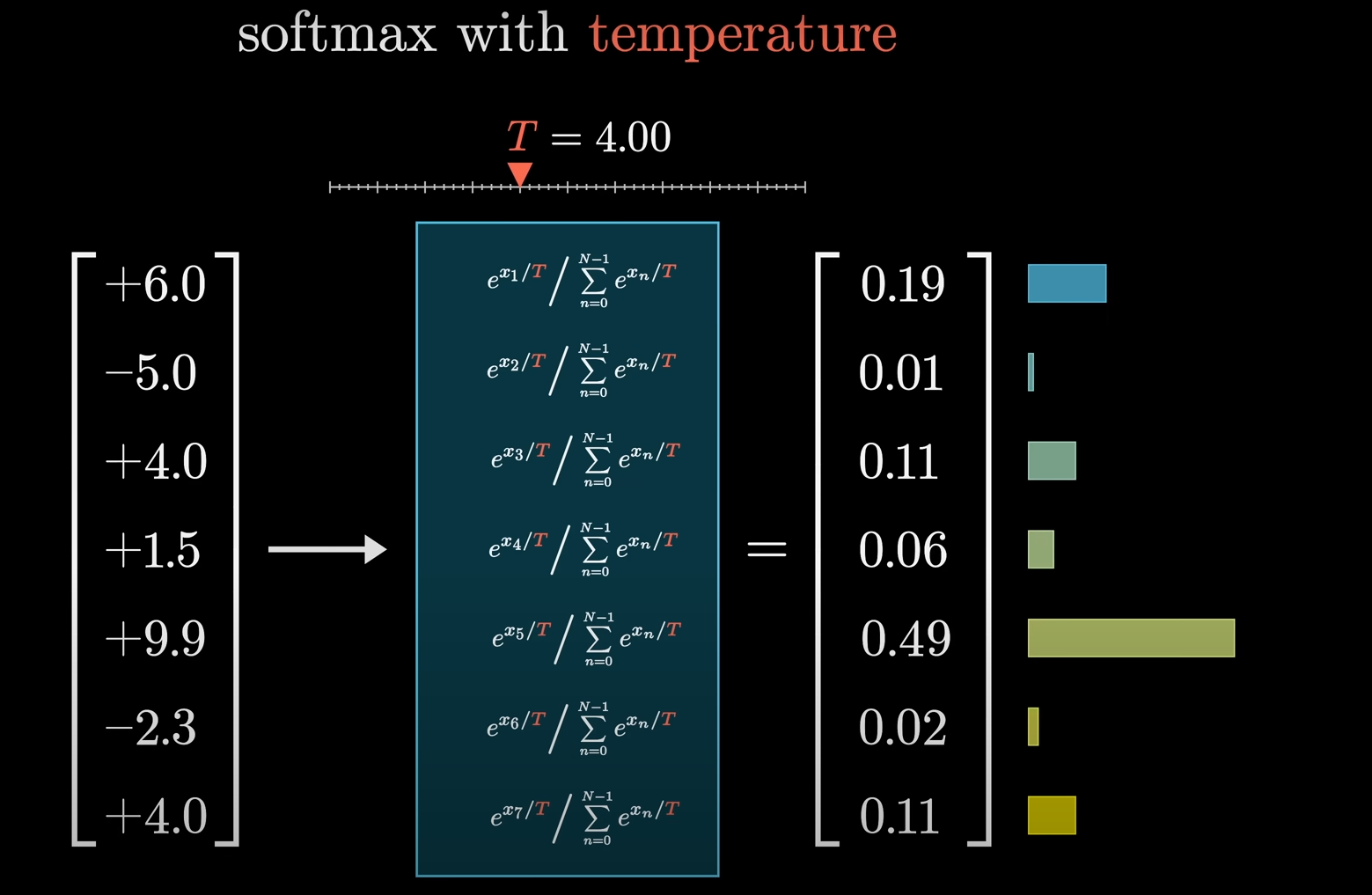

In some cases, a parameter called temperature is used in the Softmax function. A higher temperature makes the distribution more uniform, giving less likely words a better chance of being chosen, which can lead to more creative, but also more nonsensical, output. A lower temperature makes the most likely words even more dominant, leading to more predictable output.

As you can see, the temperature makes the generated content even richer.

How does this work behind the scenes?

Basically we divide both the individual values and the total sum as well with a temperature value

So each individual value becomes:

And the sum becomes:

Transformers: How the Attention mechanism works.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eMlx5fFNoYc&list=PLZHQObOWTQDNU6R1_67000Dx_ZCJB-3pi&index=7 (must watch)

Note: For people who only want to study for the sake of exams, learning till transformers is more than enough.

However, for the really curious people who want to know how the attention mechanism works, which really is the selling point of the transformer, this section is for you.

The attention mechanism is the heart of the Transformer. It's the key innovation that allows these models to understand context by letting words in a sentence "talk" to one another. Instead of processing a sentence one word at a time, attention allows the model to look at the entire sentence simultaneously and decide which words are most relevant to each other.

To understand it, let's break down how a single attention head works—a full Transformer has many of these working in parallel.

Step 1: Query, Key, and Value Vectors

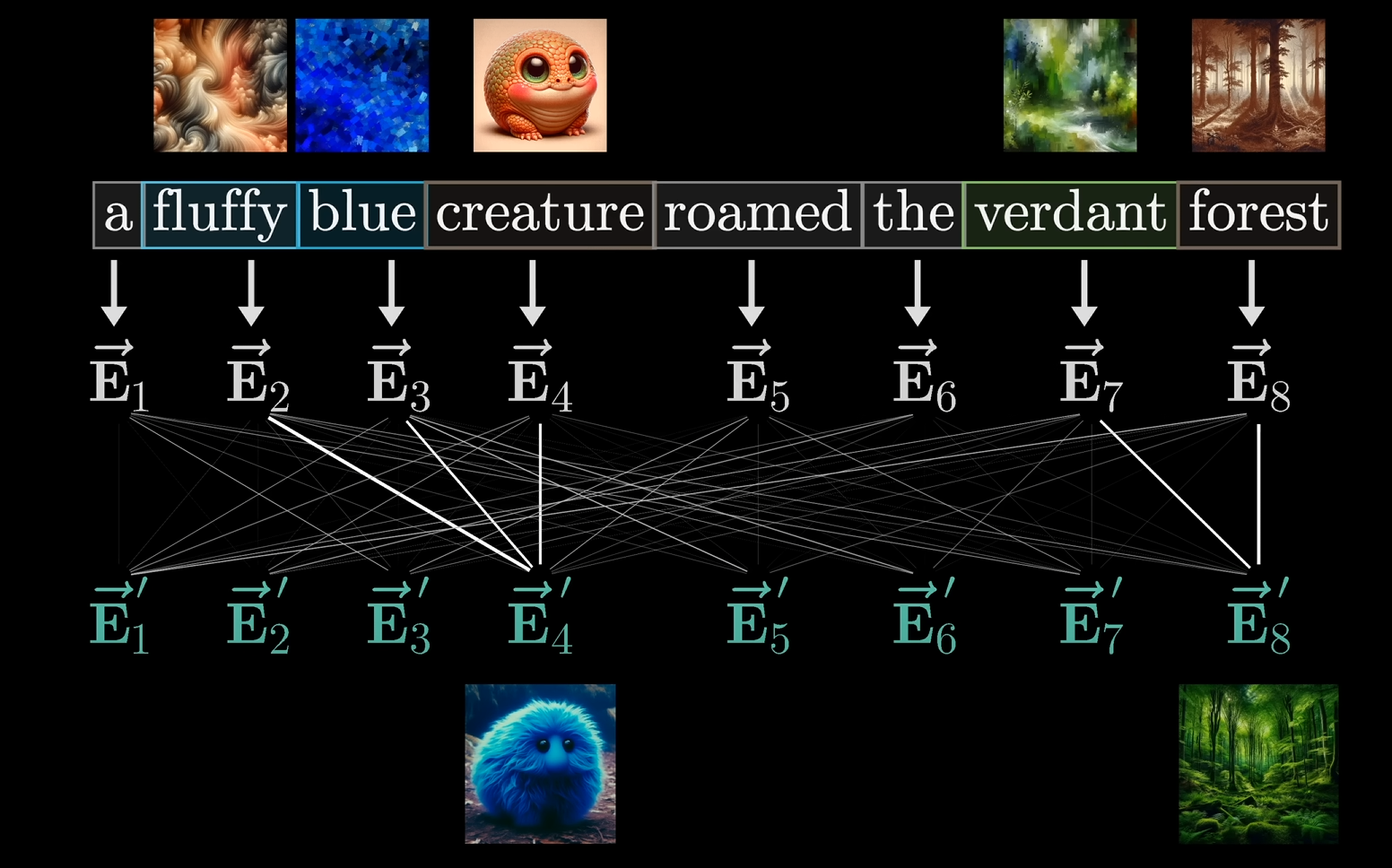

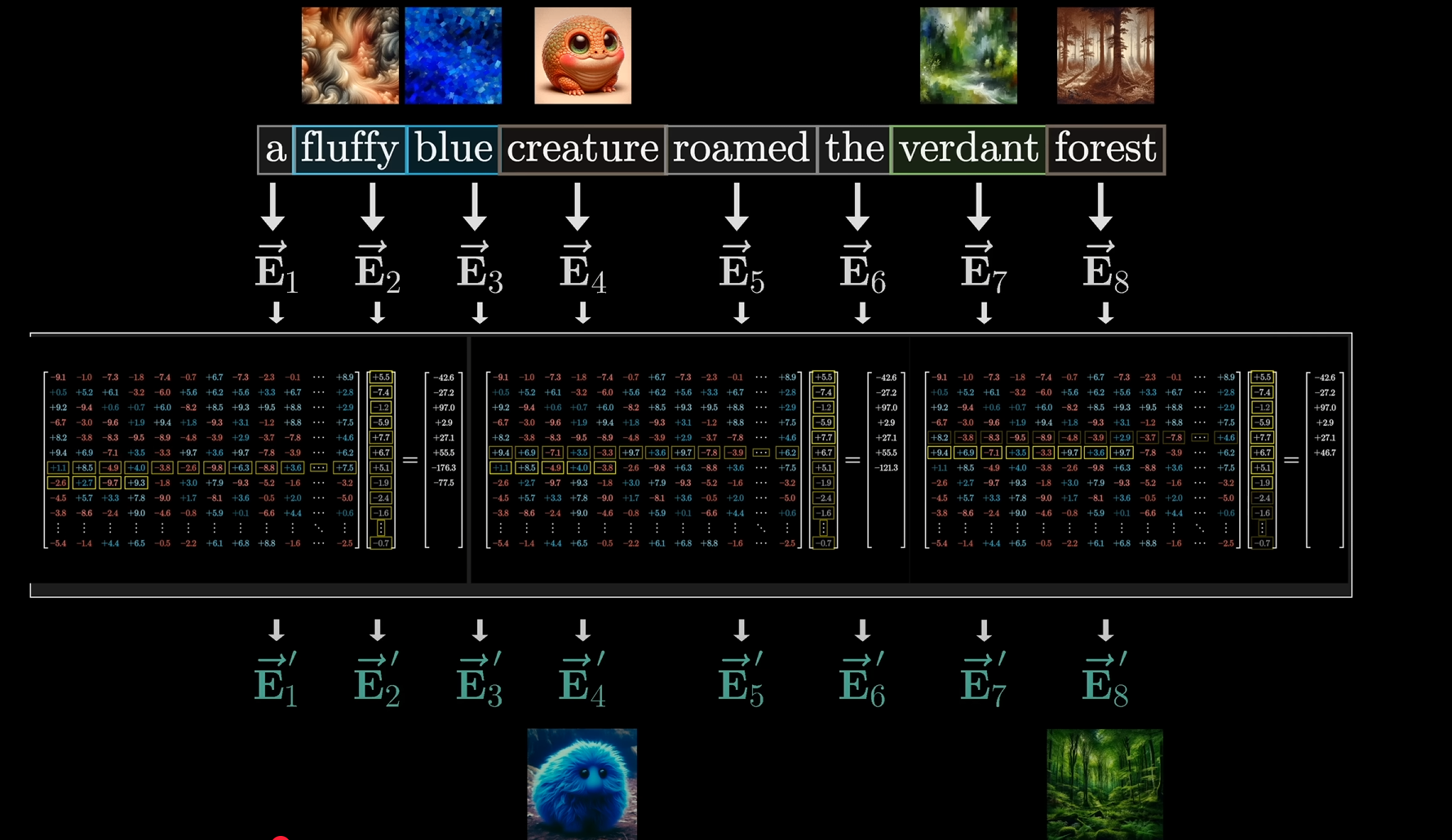

For example let's say we took this sentence:

"a fluffy blue creature roamed the verdant forest".

Our only goal here is to properly get the network to predict the correct nouns after their adjectives.

So the initial embedding matrix would look like this:

Note how, there's no correlation between any of the words.

The goal is to perform such a computation, that the end result is this:

That the network actually learns that we are talking about a fluffy blue creature that roamed the verdant forest.

That would be possible via each vector let's say

This is where things get interesting! For every token in the input, the model creates three different vectors, each with a different purpose:

-

Query vector (Q): This is like a question or a request. For each word, its query vector asks, "What other words in this sentence are relevant to me?"

-

Key vector (K): This is like an answer or a label. Each word's key vector says, "Here's what I have to offer. What am I about?"

-

Value vector (V): This is the actual information or content. The value vector for a word holds the information that should be passed to other words if its key and another word's query align.

These three vectors are created by taking the original embedding of a word and multiplying it by three distinct learned matrices: the Query Matrix (

Step 2: Calculating Attention Scores

This is where the magic happens. To figure out which words are relevant to which, the model calculates a score for every possible pair of words. It does this by taking the dot product of each word's Query vector (Q) with every other word's Key vector (K).

Remember the dot product (cosine-similarity) from before? It's a measure of similarity. So, a large dot product between a query and a key means the words they represent are highly relevant to each other. This creates a grid of scores that tells the model how much attention each word should pay to every other word.

Analogy: Imagine you're at a party. The Query is you asking a question, like "Who knows about medieval history?" The Keys are what everyone else is wearing on their nametags, like "Enthusiastic about history" or "Loves sci-fi." You'd pay more attention to the people whose keys (nametags) match your query (question), right? This is what the dot product does.

Step 3: The Softmax Function: Normalizing the Scores

We already learnt this previously.

The scores from the previous step can be any number. To turn them into weights, we use the Softmax function on the scores in each row. This converts the raw scores into a set of probabilities that add up to 1. This means the model now has a percentage-based score for how much attention each word should give to every other word.

A key detail here is Masking. When the model is predicting the next word, it can't "cheat" by looking at words that come after it. To prevent this, the attention scores for future words are set to negative infinity before the Softmax function is applied. After Softmax, these scores become zero, effectively hiding future information.

Step 4: Creating the New, Context-Rich Embeddings

Now that we have the weights, we can update the embeddings. The model creates a new vector for each word by taking a weighted sum of all the Value vectors (V) in the sentence. The weights for this sum are the normalized attention scores we just calculated.

For each word, the new vector is calculated as follows:

This is where all the information comes together. If a word's query had a high score with another word's key (e.g., "fluffy" and "creature"), then the Value vector from "fluffy" will contribute a lot to the new, updated vector for "creature." This new vector for "creature" now encodes not just the word's meaning, but the contextual meaning of a "fluffy blue creature."

The new, updated vectors are then passed to the next layer of the transformer. This entire process is repeated across multiple layers, allowing the vectors to become more and more rich with contextual information.

Multi-Headed Attention: Doing It All at Once

A full attention block doesn't just have one of these heads; it has many, each with its own set of

One head might learn to connect adjectives to nouns, while another might learn to connect pronouns to their subjects. By running them all in parallel and combining their outputs, the model can capture many different kinds of contextual relationships at the same time. This is what gives the model its immense power to understand complex language.

And that people, finally concludes the Deep Learning marathon with LLMs and Transformers as well.

Now, neural networks, large language models, will no longer be a mysterious object ever.

Modeling Time Series data: Pre-requisite -- Feature Representation Learning

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aCLMeJuGx9k&list=PLegWUnz91WfsELyRcZ7d1GwAVifDaZmgo&index=20

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e3GaXeqrG9I&list=PLegWUnz91WfsELyRcZ7d1GwAVifDaZmgo&index=21

https://viso.ai/deep-learning/representation-learning/

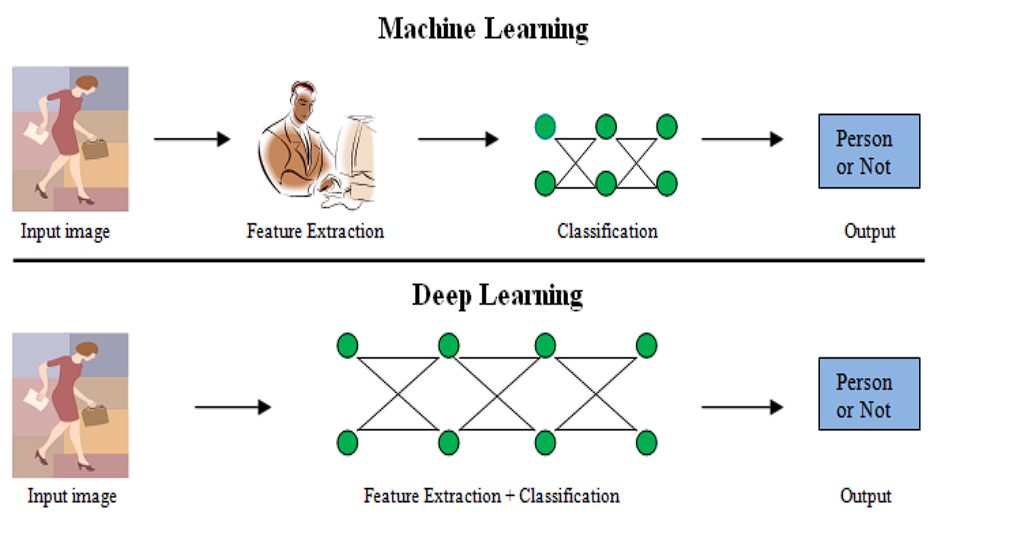

Representation Learning

Representation learning is a key idea in modern machine learning, especially in deep learning. The goal is to let the algorithm automatically learn what features to use to represent data, rather than having a human painstakingly hand-craft them. For example, instead of a human defining "is this word food-related?" a machine can learn this on its own.

For example, if we take the words on these picture, food, delicious chicken, kitchen, see how close they are to each other, similar to words like: music, saxophone, piano.

The core idea is that a word's meaning can be inferred from the context it appears in. For instance, in the sentence "Marco saw a furry little whomp amuck hiding in the tree," even though "whomp amuck" is a made-up word, you get a sense of its meaning from the surrounding words like "furry," "little," and "tree." This insight allows us to represent words in a continuous space, capturing relationships that go beyond simple binary features.

Word Embeddings: Words as Vectors

Instead of a word being a single, isolated entry in a vocabulary list, representation learning gives each word a vector—a list of numbers. This vector acts as the word's coordinates in a high-dimensional space. The idea is that words with similar meanings or that appear in similar contexts will have vectors that are close to each other in this space.

This is a powerful concept because it captures semantic meaning. You can perform arithmetic on these vectors to understand relationships, such as the classic analogy:

Word2Vec: The Core Algorithm

https://github.com/dav/word2vec

Word2Vec is a popular and efficient algorithm for learning these word vectors, or word embeddings. While it's commonly used in deep learning, it's actually a very shallow algorithm itself. It's an iterative process that works a lot like stochastic gradient descent, updating its parameters (the word vectors) one example at a time.

How It Works: The Intuition

Word2Vec works by a simple, elegant objective: it tries to predict the words that are likely to appear near a given word. It does this by creating two sets of vectors:

-

Word vectors (W): The representations of the words themselves.

-

Context vectors (C): The representations of the words that appear in the context.

The goal is to update these vectors so that the dot product of a target word's vector and its context words' vectors is high, while the dot product of the target word's vector and the vectors of random, non-context words is low.

After the training is complete, the model discards the context vectors and keeps only the word vectors (W), which are now rich with semantic and contextual information.

Key Components:

There are two main parts to Word2Vec:

-

Skip-Gram: This is the model architecture that tries to predict context words from a target word. For a given sentence, it takes one word (the "target") and tries to predict the words in its surrounding window.

-

Negative Sampling: This is the training objective that makes the process efficient. Instead of forcing the model to predict every word in the vocabulary that isn't in the context, it only presents a small, randomly selected set of "negative" words. This makes the training much faster, as it only needs to update a few vectors at a time.

Why Word2Vec is So Useful:

Word2Vec gained immense popularity because it's:

- Fast and Efficient: It can process massive amounts of text data very quickly, which is crucial for training effective models.

- Scalable: It can be easily distributed across multiple computers.

- Versatile: The learned word embeddings are a powerful feature that can be used for many different downstream tasks in natural language processing (NLP), like sentiment analysis, machine translation, or text classification.

How a single word is actually converted to a vector, i.e. a list of numbers.

In a trained Word2Vec model, converting a word to its vector is a straightforward process. It's essentially a simple lookup operation, not a complex calculation. The model's "brain" is a large matrix known as the embedding matrix or word embedding matrix.

Here's how it works in a trained model:

-

Vocabulary and Indexing: First, the model creates a fixed vocabulary of all the unique words it encountered during its training. Each word in this vocabulary is assigned a unique integer ID or index. For example, "cat" might be index 100, and "dog" might be index 101.

-

The Embedding Matrix (from Step 2 The Embedding Matrix From Words to Vectors in transfomers): The embedding matrix is a large table where each row corresponds to a word in the vocabulary, and each column corresponds to a dimension in the vector. If your vocabulary has 50,000 words and you've chosen a vector size of 300 dimensions, your embedding matrix would be a 50,000 x 300 table.

- The Lookup: When you want to convert a word into its vector, the model takes the word's integer ID and uses it to look up the corresponding row in the embedding matrix. That specific row is the word's vector.

Example: If you want the vector for the word "king":

- The model looks up "king" in its vocabulary and finds its index, let's say it's 20.

- The model then goes to the embedding matrix and retrieves the entire 20th row.

- This row is a list of 300 numbers (e.g.,

[0.12, -0.45, 0.78, ..., 0.22]). This list of numbers is the vector representation of the word "king."

This process is highly efficient, so even with very large vocabularies and high-dimensional vectors, the conversion is almost instantaneous.

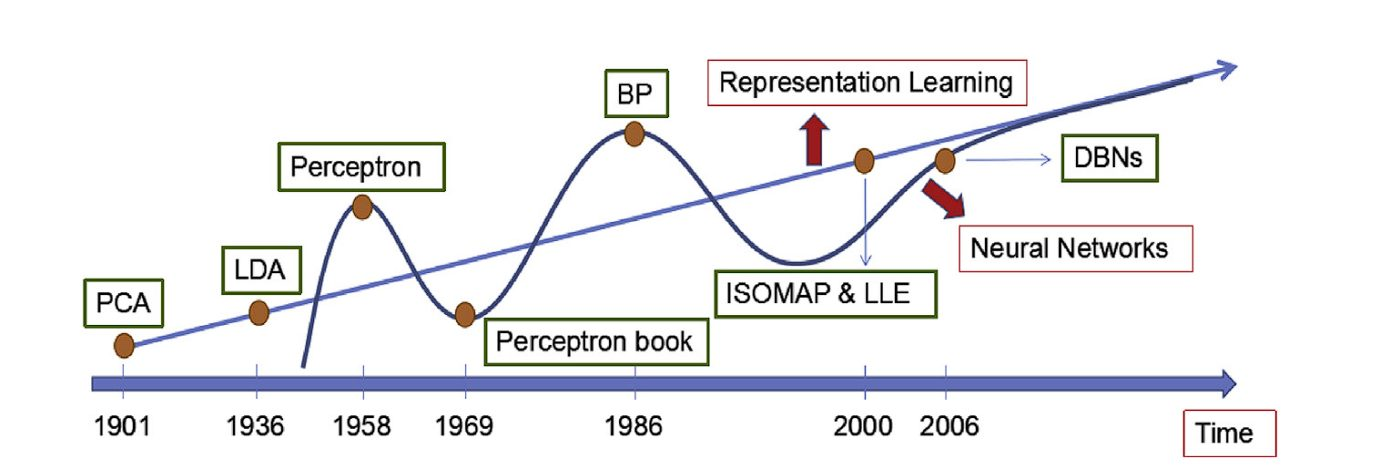

History of Representation Learning

Representation Learning has advanced significantly. Hinton and co-authors’ breakthrough discovery in 2006 marks a pivotal point, shifting the focus of representation learning towards Deep Learning Architectures. The researchers’ concept of employing greedy layer-wise pre-training followed by fine-tuning deep neural networks led to further developments.

Here is a quick overview of the timeline.

- Traditional Techniques (Pre-2000):

-

Linear Methods:

-

Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Focuses on capturing overall data variance for dimensionality reduction.

-

Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA): Emphasizes maximizing separation between classes in the low-dimensional space.

-

-

Kernel: Researchers created techniques like Kernel PCA to manage non-linear data by projecting it into a higher-dimensional space before applying linear methods.

-

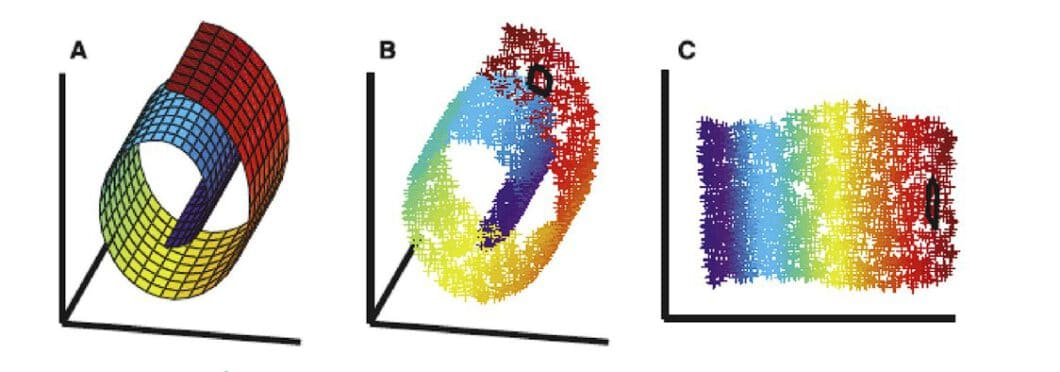

Manifold Learning (2000’s): This approach emerged to discover the intrinsic low-dimensional structure (manifold) hidden within high-dimensional data.

-

- Deep Learning Era (2006 onwards):

- Neural Networks: The introduction of deep neural networks by Hinton et al. in 2006 marked a turning point. Deep Neural Network models could learn complex, hierarchical representations of data through multiple layers. Eg, CNN, RNN, Autoencoder, and Transformers.

We have already covered the first part, i.e. Linear Methods, PCA and such, and also neural networks and their base, even transformers, so moving on, we will be focusing on the concepts of CNNs, RNNs and Autoencoders.

What is a Good Representation?

What really classifies a piece of information as a "good representation" of it's original form?

A good representation has three characteristics: Information, compactness, and generalization.

-

Information: The representation encodes important features of the data into a compressed form.

-

Compactness:

-

Low Dimensionality: Learned embedding representations from raw data should be much smaller than the original input. This allows for efficient storage and retrieval, and also discards noise from the data, allowing the model to focus on relevant features and converge faster.

-

Preserves Essential Information: Despite being lower-dimensional, the representation retains important features. This balance between dimensionality reduction and information preservation is essential.

-

-

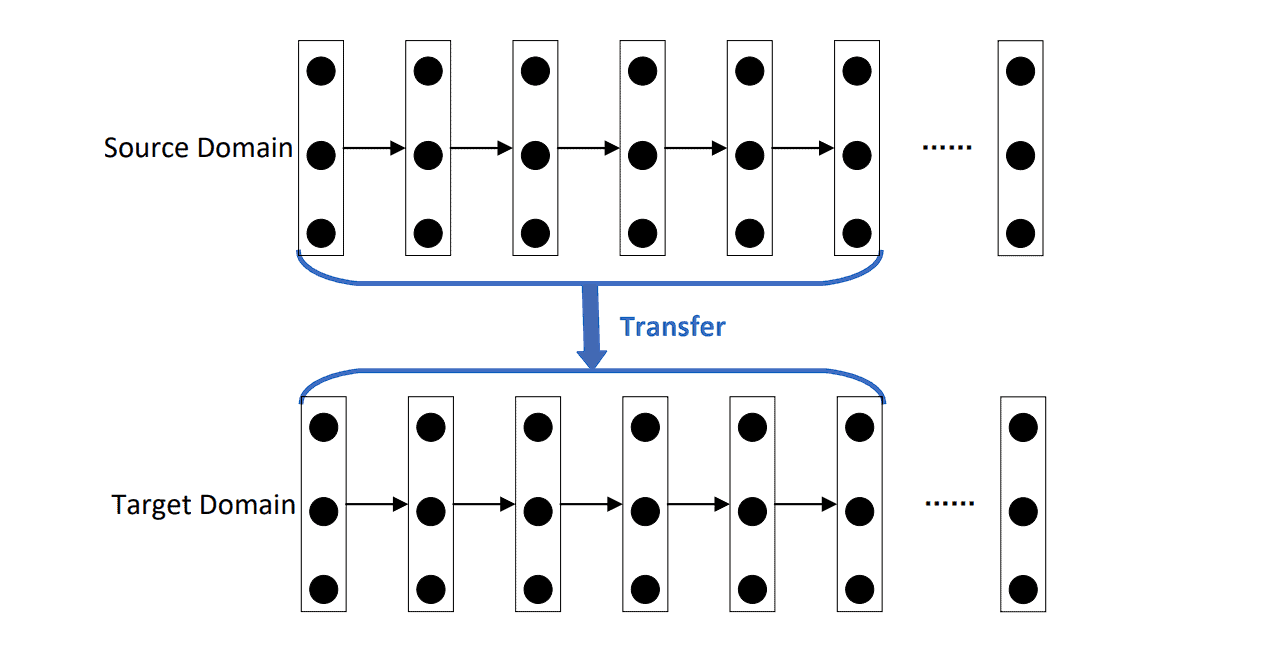

Generalization (Transfer Learning): The aim is to learn versatile representations for transfer learning, starting with a pre-trained model (computer vision models are often trained on ImageNet first) and then fine-tuning it for specific tasks requiring less data.

Supervised vs Unsupervised deep learning in feature representation learning

Deep Learning tasks can be divided into two categories: Supervised and Unsupervised Learning. The deciding factor is the use of labeled data.

-

Supervised Representation Learning:

-

Leverages Labeled Data: Uses labeled data. The labels guide the learning algorithm about the desired outcome.

-

Focuses on Specific Tasks: The learning process is tailored towards a specific task, such as image classification or sentiment analysis. The learned representations are optimized to perform well on that particular task.

-

Examples:

- Training a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to classify objects in images (e.g., dog, cat) using labeled image datasets, or a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) for sentiment analysis of text data (positive, negative, neutral) with labeled reviews or sentences.

-

-

Unsupervised Representation Learning:

-

Without Labels: Works with unlabeled data. The algorithm identifies patterns and relationships within the data itself.

-

Focuses on Feature Extraction: The goal is to learn informative representations that capture the underlying structure and essential features of the data. These representations can then be used for various downstream tasks (transfer learning).

-

Examples:

-

Training an autoencoder to compress and reconstruct images, learning a compressed representation that captures the key features of the image.

-

Using

Word2VecorGloVeon a massive text corpus to learn word embeddings, where words with similar meanings have similar representations in a high-dimensional space. -

BERT to learn contextual representation of words.

-

-

Supervised Feature Representation Learning.

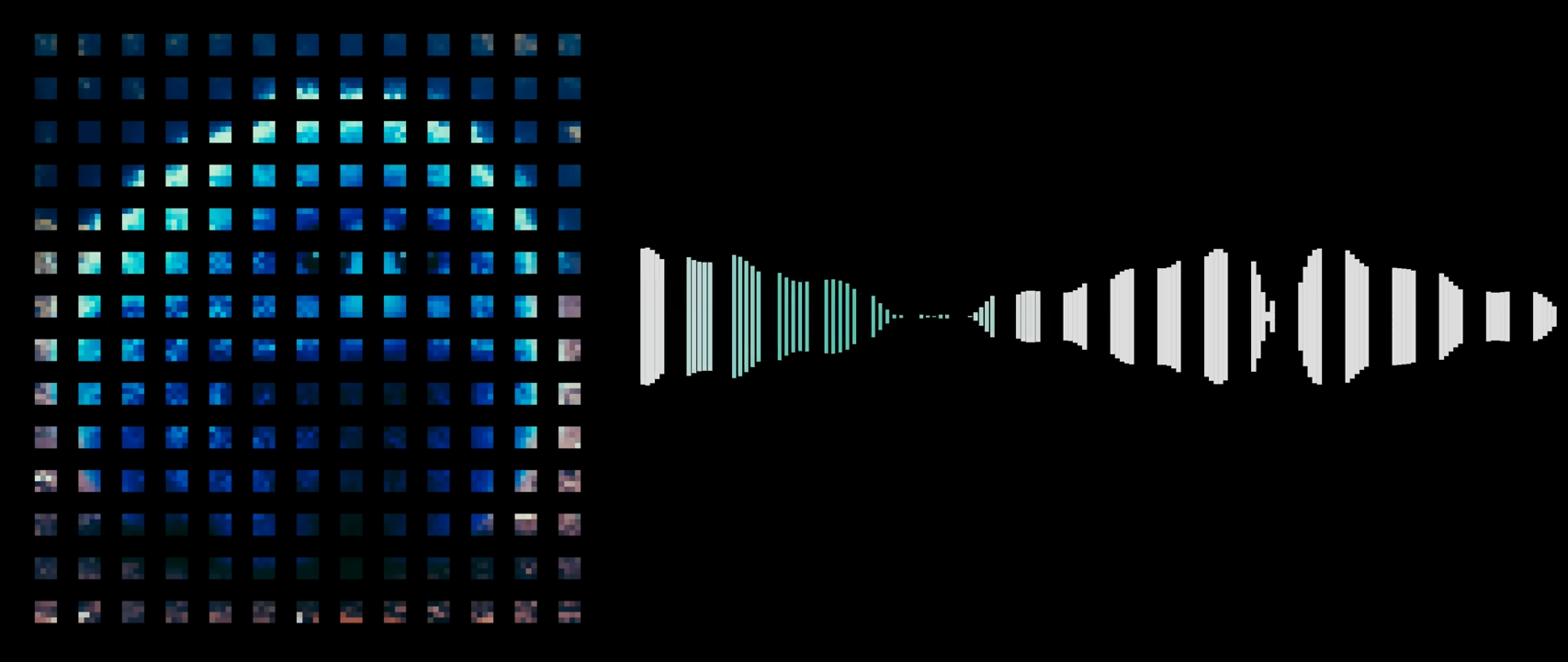

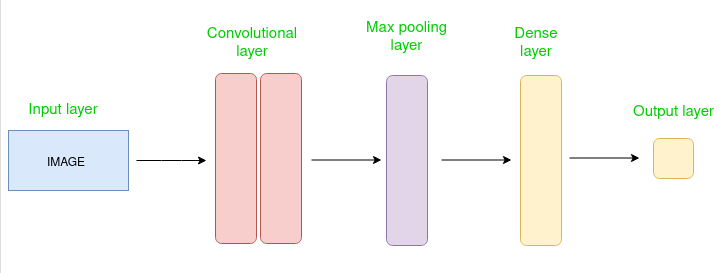

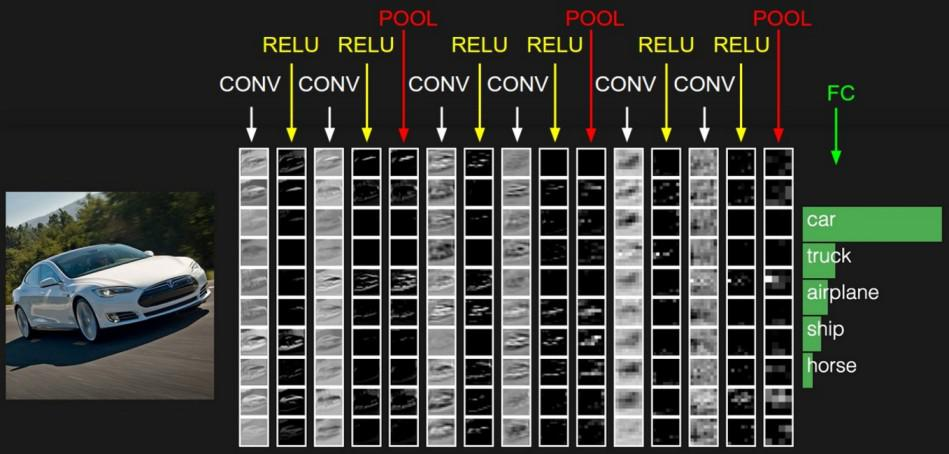

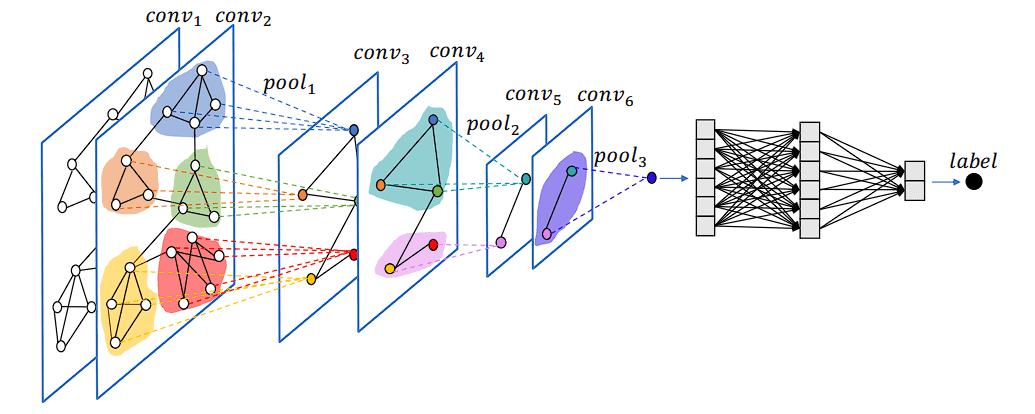

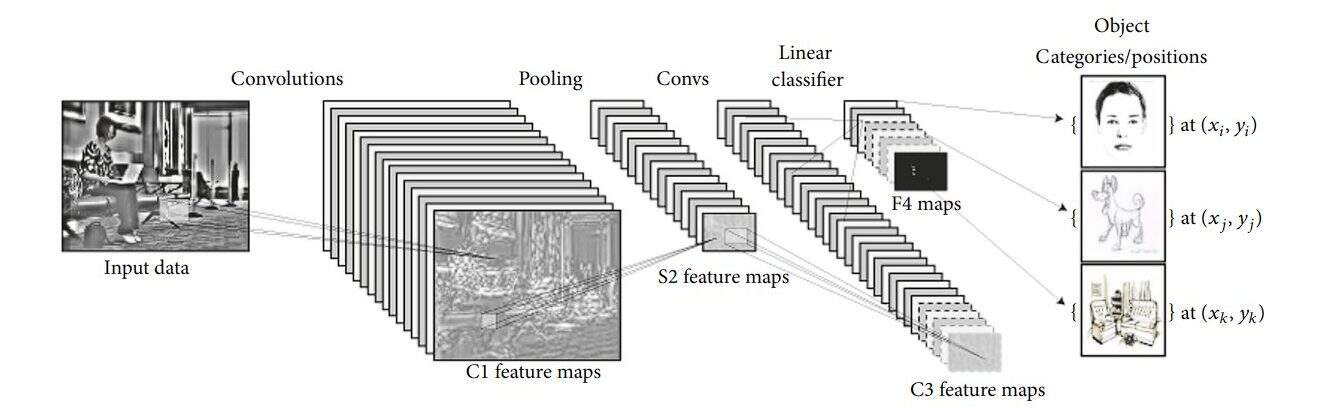

1. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/machine-learning/introduction-convolution-neural-network/

Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) is an advanced version of artificial neural networks (ANNs), primarily designed to extract features from grid-like matrix datasets. This is particularly useful for visual datasets such as images or videos, where data patterns play a crucial role. CNNs are widely used in computer vision applications due to their effectiveness in processing visual data.

CNNs consist of multiple layers like the input layer, Convolutional layer, pooling layer, and fully connected layers. Let's learn more about CNNs in detail.

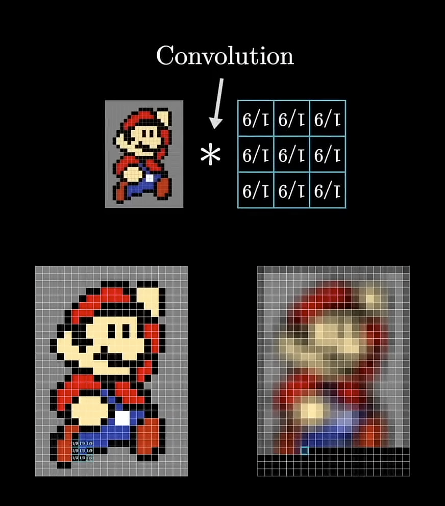

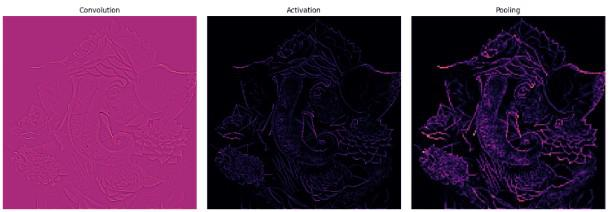

How does the Convolutional Layer work?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KuXjwB4LzSA (3blue1brown's explanation on what is convolution, must watch.)

Convolution Neural Networks are neural networks that share their parameters.

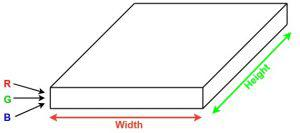

Imagine you have an image. It can be represented as a cuboid having its length, width (dimension of the image), and height (i.e the channel as images generally have red, green, and blue channels).

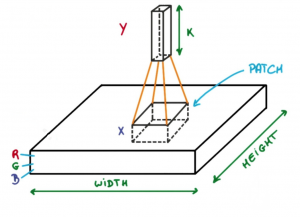

Now imagine taking a small patch of this image and running a small neural network, called a filter or kernel on it, with say, K outputs and representing them vertically.

Now slide that neural network across the whole image, as a result, we will get another image with different widths, heights, and depths. Instead of just R, G, and B channels now we have more channels but lesser width and height. This operation is called Convolution. If the patch size is the same as that of the image it will be a regular neural network. Because of this small patch, we have fewer weights.

TLDR: If we reference back to how time series analysis is done over "sliding windows"(the filters/kernels), this is the same thing, but as we keep on sliding the neural network across the whole image, we keep on taking small "slices" or patches of the whole image, each having different widths, heights, and depths, each decreasing as we keep going.

We learnt about the concepts of sliding windows back in Computer Networks in Module 2 -- Data Link Layer -- Computer Networks#2. Go Back -N ARQ.

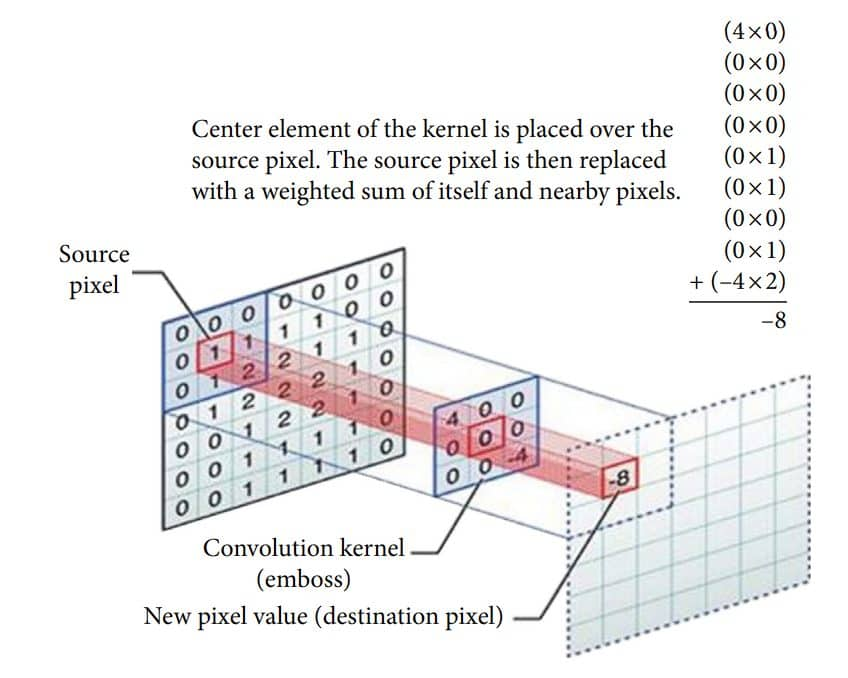

The filters/kernels are smaller matrices usually 2x2, 3x3, or 5x5 shape. it slides over the input image data and computes the dot product between kernel weight and the corresponding input image patch.

What this results in, is the smaller the image slice, the smaller it's dimensions, the lesser weights we need for that data. It's basically a form of sparse modeling.

The math behind the CNN

The entire process boils down to a dot product operation, which you're already familiar with from our previous discussions on vectors. Think of the filter as a small grid of numbers, and a patch of the input image as a grid of numbers.

Let's imagine a simple 2D example.

-

Filter: a 3x3 grid of numbers (e.g.,

1, 0, 1], [0, 1, 0], [1, 0, 1). -

Image Patch: a 3x3 section of your input image's pixel values.

To perform the convolution, you simply place the filter over an image patch and multiply the corresponding numbers together. Then you add up all the results to get a single number. This is the dot product.

Suppose we use a total of 12 filters for this layer we’ll get an output volume of dimension 32 x 32 x 12.

The Process: Sliding the Filter

This single-step dot product is then repeated across the entire image.

-

Slide: The filter starts in the top-left corner of the image.

-

Compute: The dot product is calculated between the filter and the patch of the image it's currently on.

-

Repeat: The filter then slides to the next position, as defined by the stride (how many pixels it moves at a time).

-

Create an Output Map: This process is repeated until the filter has covered the entire image. Each dot product result becomes a single pixel in a new output grid called a feature map.

If your input image has a depth (e.g., 3 channels for Red, Green, and Blue), the filter also has that same depth. The dot product is then calculated across all channels to produce a single value.

The network learns the optimal numbers inside these filters through backpropagation. These numbers are the "weights" of the CNN. Different filters learn to detect different features in the image, such as edges, curves, or textures. Stacking the resulting feature maps together gives you an output volume.

The Activation Layer

This layer basically handles in generating the activation value by taking the in weighted sum + biases per neuron per layer and then using an activation function to output the final activation value. Example activation functions used are mostly Tanh and Leaky RELU. (from Common Activation Functions in ANNs).

The volume remains unchanged hence output volume will have dimensions 32 x 32 x 12.

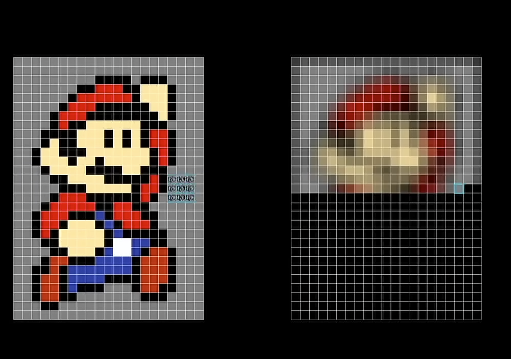

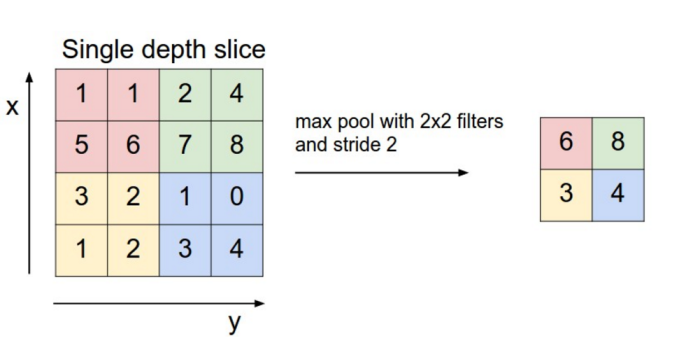

The Pooling Layer