Inter Process Communication -- Operating Systems

Inter-Process Communication (IPC)

What is Inter-Process Communication (IPC)?

IPC refers to the mechanisms that allow processes to communicate with one another. Since processes in an operating system may run in isolation and have separate memory spaces, IPC provides a way for them to share data, send messages, or synchronize their activities.

IPC is crucial for enabling cooperation between processes, particularly in multitasking or distributed environments.

Why is IPC Necessary?

- Data Sharing: Processes may need to share data, such as files or variables, without directly accessing each other’s memory spaces.

- Synchronization: Processes often need to synchronize their activities, especially when they rely on shared resources (e.g., semaphores, locks).

- Modularity: In systems that divide tasks across multiple processes, IPC allows the processes to work together to complete a larger task.

- Efficiency: IPC can enhance system performance by allowing parallel execution of tasks.

Types of IPC Mechanisms

IPC can be achieved using various methods, each suited to different communication and synchronization needs. Let’s look at some of the most common IPC techniques:

1. Pipes

Pipes are one of the simplest IPC mechanisms and are commonly used in Unix-like operating systems.

- Definition: A pipe provides a one-way flow of data from one process to another. The output of one process becomes the input of the next.

- Unidirectional: Pipes are typically unidirectional, meaning data flows in only one direction.

- Anonymous Pipes: These are commonly used for communication between related processes, such as a parent and child process.

- Named Pipes (FIFOs): Unlike anonymous pipes, named pipes can be used between unrelated processes and are identified by a specific name in the filesystem.

Example of Pipe in Unix:

$ ls | grep ".txt"

In this example, the output of ls (list directory contents) is passed through the pipe to the grep command to filter files with the .txt extension.

2. Message Queues

Message queues provide a way for processes to communicate by sending and receiving messages via a queue.

- Definition: A message queue is a linked list of messages stored within the kernel. Processes communicate by sending messages to the queue and reading messages from it.

- Advantages: Unlike pipes, message queues allow processes to send structured messages, and messages can be read in any order (not necessarily FIFO).

- Asynchronous: Sending a message to a queue is non-blocking, and the sender does not need to wait for the receiver to pick up the message.

Use Case: Message queues are used in situations where messages need to persist if the recipient isn’t immediately available.

3. Shared Memory

Shared memory is the fastest form of IPC because it allows multiple processes to directly access the same region of memory.

- Definition: Shared memory involves mapping a portion of memory that multiple processes can read and write to.

- Efficiency: Because processes don’t have to go through the kernel to exchange data, shared memory is the most efficient method of IPC.

- Synchronization: Shared memory typically requires additional synchronization mechanisms (like semaphores or mutexes) to prevent race conditions.

Example: Two processes sharing a block of memory to exchange data without repeatedly copying it between their memory spaces.

4. Semaphores

Semaphores are primarily used for process synchronization, but they can also be used for signaling between processes.

- Definition: A semaphore is a signaling mechanism that controls access to shared resources. It can be thought of as a counter that keeps track of how many processes can access a resource.

- Binary Semaphore: Also known as a mutex, it allows only one process to access the resource at a time (like a lock).

- Counting Semaphore: It allows multiple processes to access a resource, but only up to a certain limit.

Use Case: Semaphores are typically used to ensure mutual exclusion (i.e., only one process can access a critical section of code at a time).

5. Sockets

Sockets are primarily used for communication between processes over a network, but they can also be used for communication between processes on the same machine.

- Definition: A socket provides a bidirectional communication channel between two processes, either on the same machine or across a network.

- Socket Types:

- Stream Sockets: Provide a connection-oriented communication, typically using TCP.

- Datagram Sockets: Provide connectionless communication, typically using UDP.

Use Case: Sockets are commonly used in client-server applications, such as web servers communicating with web browsers.

6. Signals

Signals are a mechanism used by the operating system to notify processes of events.

- Definition: A signal is a small message sent to a process to notify it of an event, such as an interrupt or a termination request.

- Asynchronous: Signals are delivered asynchronously, meaning the receiving process does not need to be waiting for the signal.

- Signal Handling: Processes can register signal handlers to specify how they should respond when receiving a signal.

Example: A process receiving the SIGKILL signal to terminate its execution.

7. Memory-Mapped Files

Memory-mapped files allow processes to map files or devices into memory, enabling them to share memory through file I/O.

- Definition: Memory-mapped files are a region of memory that can be accessed by multiple processes, backed by a file on disk.

- Efficiency: Instead of reading and writing files using traditional I/O, processes can treat the file as if it were part of their address space, speeding up access.

Use Case: Sharing large datasets between processes without duplicating the data in memory.

Critical Section

A critical section is a segment of code in a process where shared resources are accessed. It is critical because multiple processes may try to execute this code concurrently, leading to unpredictable outcomes if proper synchronization is not applied.

Characteristics of a Critical Section:

- Shared Resource Access: The critical section typically involves reading from or writing to shared variables, files, or other resources.

- Mutual Exclusion: To prevent errors, only one process should execute its critical section at any given time.

- Concurrency Control: If multiple processes attempt to execute their critical sections simultaneously, it could result in race conditions, data inconsistency, or system failures.

Example of a Critical Section:

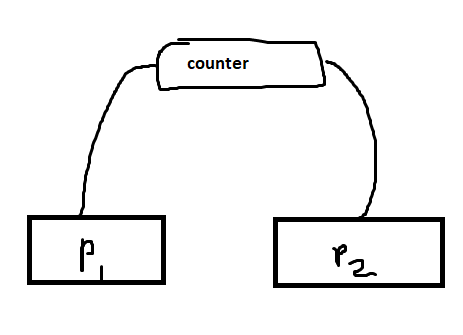

Imagine two processes, P1 and P2, both incrementing a shared variable counter. The code to increment the counter could look like this:

// Critical section for both P1 and P2

counter = counter + 1;

Without proper synchronization, P1 and P2 could both read the current value of counter, increment it, and write the same result back. This could lead to lost updates, where the counter is only incremented once, even though both processes ran the increment operation.

Critical Section Problem:

The Critical Section Problem is to design a protocol that ensures:

- Mutual Exclusion: Only one process can execute the critical section at a time.

- Progress: If no process is in the critical section, one of the waiting processes must be allowed to enter it.

- Bounded Waiting: No process should have to wait indefinitely to enter the critical section.

This problem is a core issue in concurrent programming, and solving it is necessary for ensuring data integrity when multiple processes or threads are involved.

Race Conditions

A race condition occurs when the behavior of a program depends on the relative timing or order of execution of multiple processes or threads that access shared resources. This leads to unpredictable and often undesirable outcomes.

How Race Conditions Arise:

Race conditions typically occur in concurrent systems, where multiple processes or threads run in parallel and access shared resources (like memory, files, or hardware). The problem arises when these processes or threads execute in an unsynchronized way, leading to incorrect results.

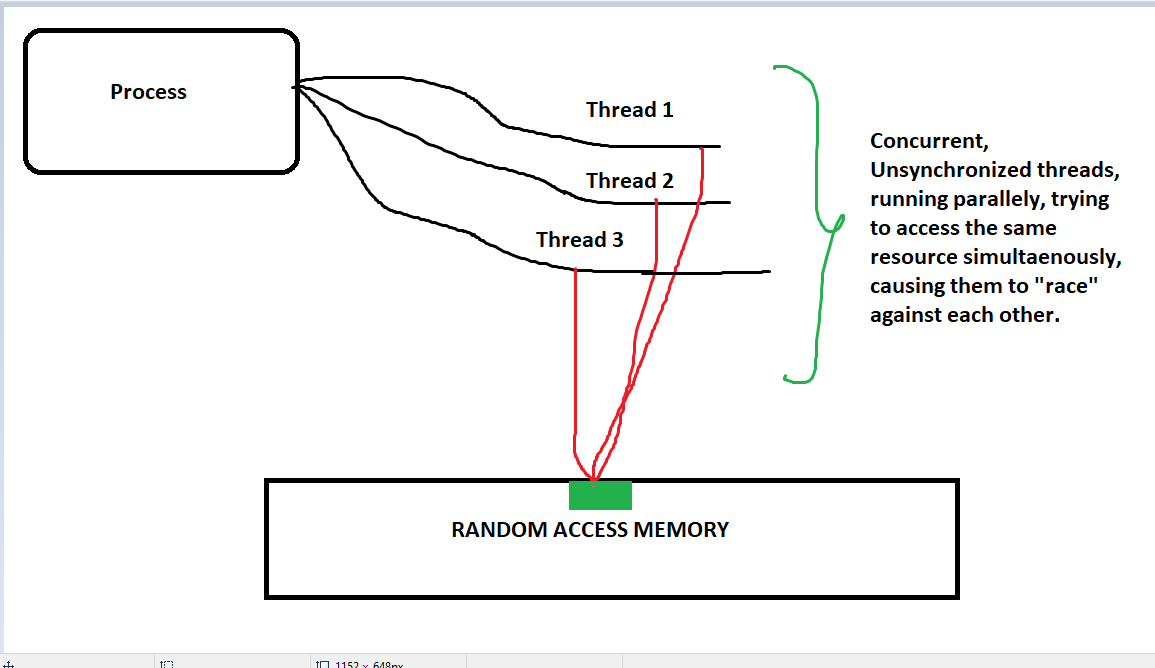

Here we can see that all the threads are trying to access and write to the same memory block at the same time, causing a "race condition", which can cause undesirable results.

The threads are running in a concurrent, asynchronous manner, which means there is "no particular order of execution" and that causes that memory block to be accessed, written to, all at the same time.

A code example could be:

counter = 5; // Initial value of counter = 5 // Process P1:

counter = counter + 1; // (Reads counter value as 5, adds 1, plans to write 6)

// Process P2:

counter = counter + 1; // (Reads counter value as 5, adds 1, plans to write 6)

If both P1 and P2 read the value of counter at the same time (which is 5), they both increment it and plan to write 6 back. The correct final value should be 7, but because of the race condition, both processes write 6, and the increment performed by one of the processes is lost.

This type of situation is called a lost update or write-after-write conflict.

Why Are Race Conditions Dangerous?

- Unpredictable Results: The program's output depends on the order and timing of execution, which can vary from run to run.

- Hard to Debug: Race conditions are often intermittent, depending on the system's timing, making them difficult to reproduce and fix.

- Data Corruption: Unprotected access to shared data can lead to data corruption, inconsistencies, and system crashes.

Avoiding Race Conditions:

To avoid race conditions, we must ensure that critical sections are executed in mutual exclusion, meaning that only one process can access the shared resource at a time. This is often achieved through:

- Locks/Mutexes: Synchronization primitives that allow a process to "lock" a resource while accessing it and "unlock" it afterward.

- Semaphores: More advanced synchronization mechanisms that control access to shared resources.

- Monitors: High-level synchronization constructs that enforce mutual exclusion.

Mutual Exclusion

Mutual exclusion is a principle in concurrent programming that ensures only one process or thread can access a shared resource or critical section at a time. It prevents race conditions and ensures data consistency when multiple processes need access to shared data.

Why is Mutual Exclusion Important?

Without mutual exclusion, when two or more processes execute their critical sections simultaneously, it can lead to unpredictable results and corrupt the shared resources they are accessing. Mutual exclusion guarantees that each process gets exclusive access to its critical section, one at a time, ensuring correctness and synchronization in concurrent systems.

Common Methods to Achieve Mutual Exclusion:

-

Locks (Mutex):

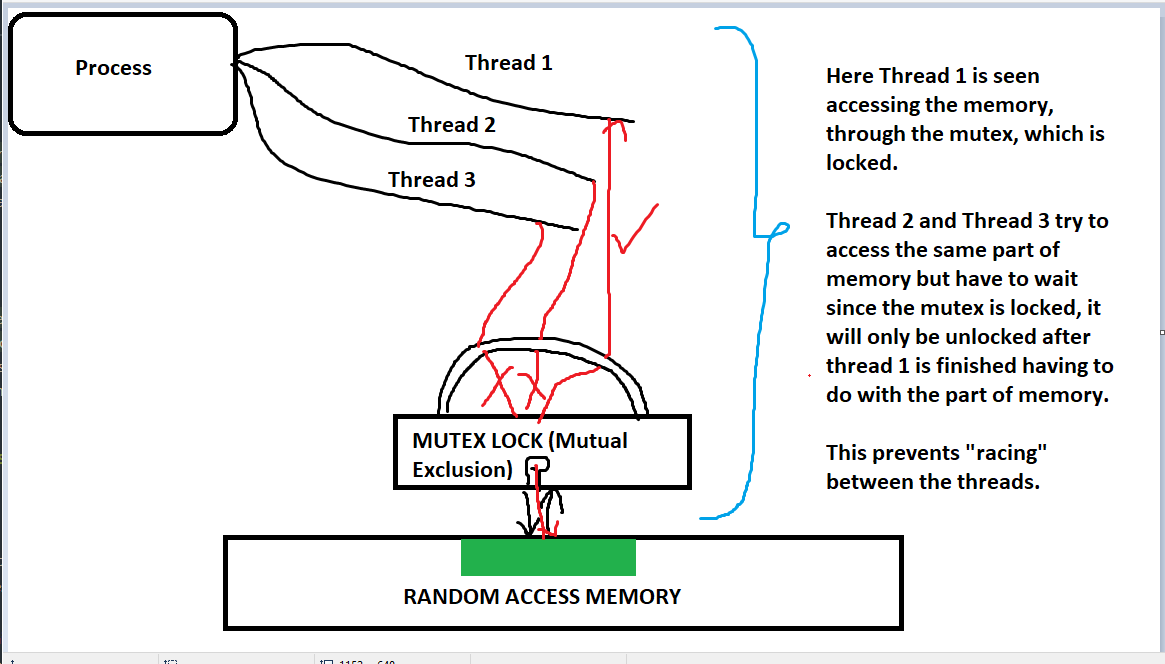

- Mutex (Mutual Exclusion) is a synchronization primitive used to protect critical sections.

- A mutex is a binary lock that can be in two states: locked or unlocked.

- Before entering a critical section, a process tries to acquire the lock. If the lock is already held by another process, the current process waits until the lock is released.

- After finishing the critical section, the process releases the lock, allowing another process to enter its critical section.

Example of mutex usage in pseudocode:

acquire_lock(mutex);

// Critical Section

counter = 5; // Initial value of counter = 5 // Process P1:

counter = counter + 1; // (Reads counter value as 5, adds 1, plans to write 6)

// Process P2:

counter = counter + 1; // will throw an error this time since the resource P2 tries to access is locked by mutex.

release_lock(mutex);

// Process P2:

counter = counter + 1; // reads counter as 6, adds 1.

-

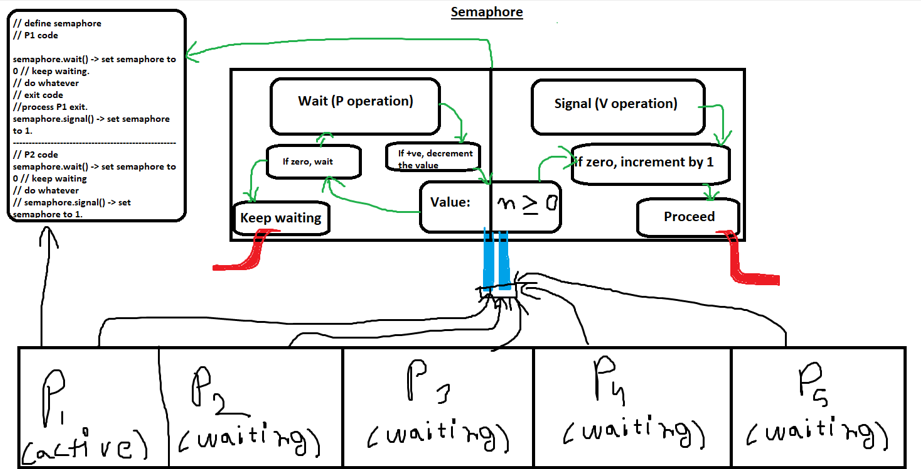

Semaphores:

- Semaphores are integer-based synchronization tools.

- A binary semaphore (or mutex semaphore) can be used to achieve mutual exclusion, but semaphores can also have values greater than 1, allowing for more complex synchronization (like limiting access to a fixed number of resources).

- Two operations are used on semaphores:

wait()(also calledP()) andsignal()(also calledV()). - A process must wait for a semaphore to become available before accessing the critical section.

-

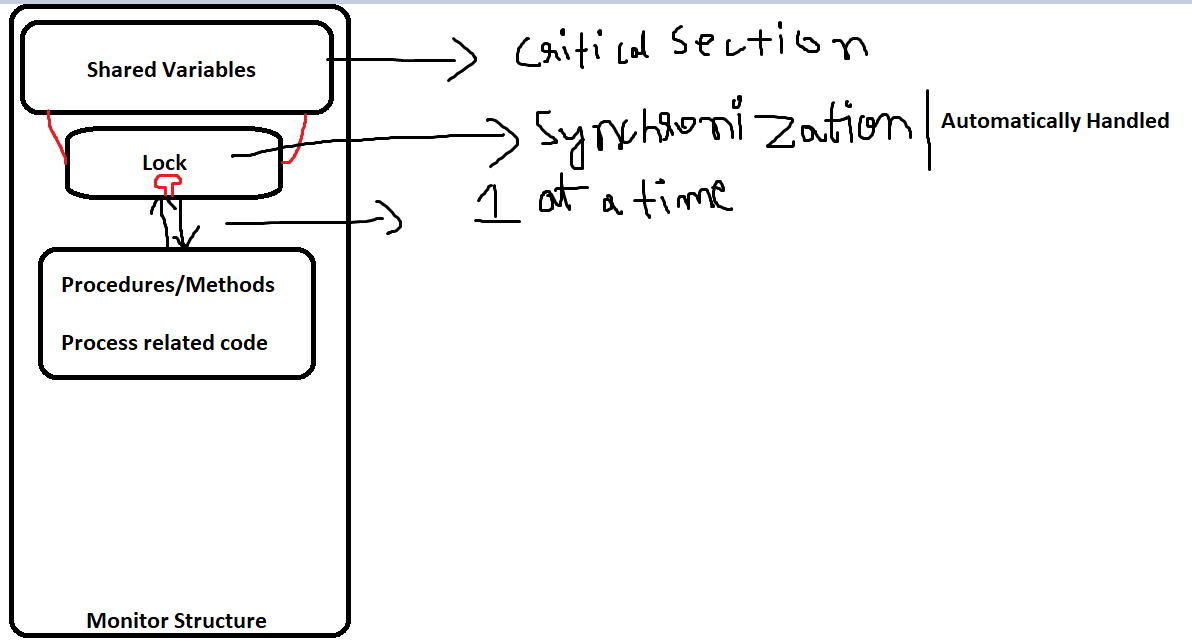

Monitors:

- Monitors are a high-level synchronization construct that automatically ensures mutual exclusion.

- They provide methods for entering and exiting critical sections, and a monitor's data is accessible only to one process at a time.

- Monitors encapsulate the shared variables and their operations inside an object-like structure, automatically handling locking and unlocking when the monitor methods are called.

monitor {

// shared variables

procedure critical_section() {

// code

}

}

-

Disabling Interrupts (in single-processor systems):

- In a single-processor environment, interrupts can be disabled when a process is inside a critical section. This prevents the operating system from switching to another process.

- However, disabling interrupts can be dangerous, as it can lead to system unresponsiveness.

-

Busy Waiting (Spinlocks):

- Spinlocks are another type of lock that repeatedly checks whether the lock is available in a loop (i.e., the process “spins” while waiting).

- This is useful when the critical section is very short and the overhead of context switching would outweigh the benefits of blocking.

- However, in systems where processes hold a lock for a long time, spinlocks can waste CPU time and are inefficient.

Mutual Exclusion Requirements:

To solve the Critical Section Problem, mutual exclusion must fulfill these conditions:

- Mutual Exclusion: Only one process can be in the critical section at any given time.

- Progress: If no process is in the critical section, then other processes should be able to enter it without unnecessary delays.

- Bounded Waiting: Each process must have a limit on how long it has to wait to enter the critical section, preventing starvation.

Drawbacks:

- Performance Overhead: Locking mechanisms, like mutexes, can introduce overhead, slowing down the system.

- Deadlock: Improper use of locking mechanisms can lead to deadlocks, where two or more processes wait indefinitely for each other to release resources.

- Starvation: If not properly managed, some processes may never get the chance to enter their critical sections, leading to starvation.

Hardware Solutions for Mutual Exclusion

To enforce mutual exclusion and avoid race conditions, several hardware-based mechanisms were introduced. These methods help to synchronize processes directly at the hardware level and are often used in low-level systems or as building blocks for higher-level synchronization mechanisms like locks or semaphores.

Key Hardware Solutions:

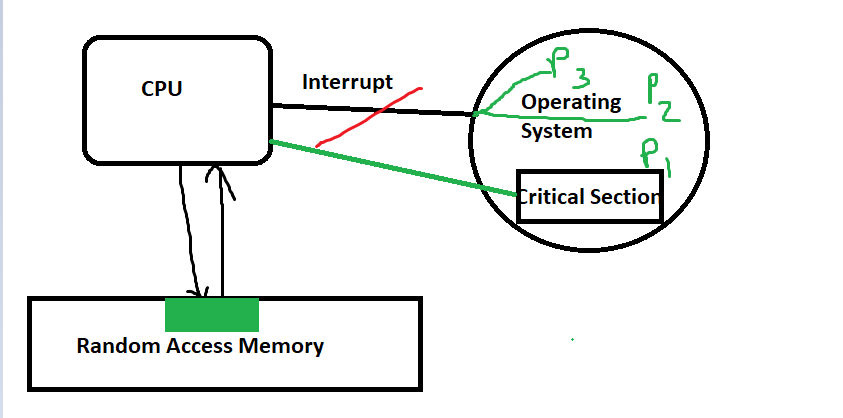

Disabling Interrupts (Single-Processor Systems):

Here Process P1 has a critical section that needs to access a memory block, so "interrupt" is disabled in the hardware in this single processor system so that processes like P2 and P3 cannot interrupt the CPU and access the same memory block.

-

In a single-processor environment, the simplest way to achieve mutual exclusion is by disabling interrupts while a process is in its critical section.

- How it works: By disabling interrupts, the process cannot be preempted (i.e., interrupted) by the operating system, ensuring that no other process can run and interfere with the shared resources.

-

Problems:

- This approach is not scalable to multiprocessor systems.

- It can make the system unresponsive if a process takes too long in its critical section.

- Only feasible in very short and controlled critical sections in kernel mode.Example in pseudocode:

disable_interrupts();

// Critical Section

enable_interrupts();

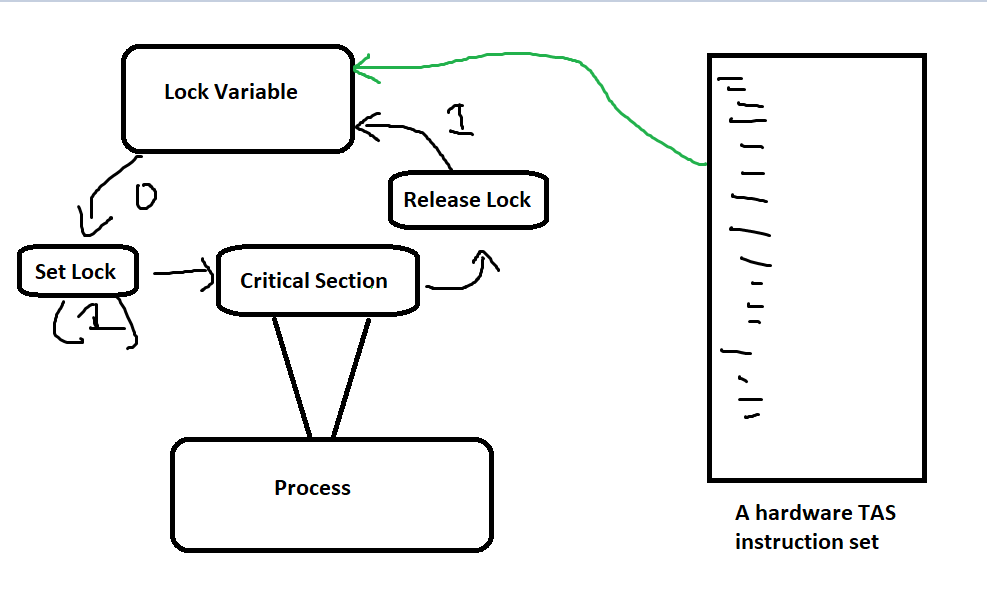

Test-and-Set (TAS) Instruction:

- The test-and-set instruction is a hardware instruction used to achieve mutual exclusion in multiprocessor environments.

- How it works: It works by testing and modifying the value of a lock variable in a single atomic (indivisible) operation.

- If the lock is available (i.e., the variable is 0), it sets the lock to 1, indicating the critical section is occupied. If the lock is already set to 1, the process keeps checking (spins) until it can acquire the lock.

- The atomicity of this instruction ensures that no other process can access or modify the lock while it's being tested or set.

Example in pseudocode:

boolean test_and_set(boolean *lock) {

boolean old_value = *lock;

*lock = true;

return old_value;

}

while (test_and_set(&lock)) {

// Wait (busy wait)

}

// Critical section

lock = false;

Issues:

- Busy-waiting can waste CPU resources (called spinlock), as the process is continuously checking the lock in a loop.

- This is inefficient in cases where the critical section is long.

Swap Instruction:

- The swap instruction is another atomic hardware instruction used to swap the values of two variables.

- How it works: The swap instruction is used to exchange a value (typically a lock variable) between two memory locations atomically.

- A process wanting to enter a critical section will swap its lock variable with a shared variable (e.g., 0 or 1) that indicates whether the critical section is free. If it succeeds, the process proceeds; otherwise, it keeps trying.

Example in pseudocode:

void swap(boolean *a, boolean *b) {

boolean temp = *a;

*a = *b;

*b = temp;

}

boolean key = true;

while (key == true) {

swap(&lock, &key); // Atomic swap

}

// Critical section

lock = false;

Compare-and-Swap (CAS) Instruction:

- The compare-and-swap (CAS) instruction is a more flexible and widely used hardware primitive for achieving synchronization.

- How it works: CAS works by checking if a memory location contains a certain value (e.g., 0). If it does, it swaps it with a new value (e.g., 1). This operation is performed atomically. If the value has changed in the meantime, the operation fails, and the process tries again.

Example in pseudocode:

boolean compare_and_swap(int *value, int expected, int new_value) {

if (*value == expected) {

*value = new_value;

return true;

}

return false;

}

while (!compare_and_swap(&lock, 0, 1)) {

// Busy wait

}

// Critical section

lock = 0;

Fetch-and-Increment:

- This is another atomic instruction used in shared-memory multiprocessor systems.

- How it works: The process uses the fetch-and-increment instruction to atomically increment a shared counter (e.g., a ticket counter). This counter is used to determine which process should enter the critical section next.

- Each process gets a unique ticket and waits for its turn to execute its critical section.

int fetch_and_increment(int *counter) {

int old_value = *counter;

*counter = old_value + 1;

return old_value;

}

int my_ticket = fetch_and_increment(&ticket_counter);

while (my_ticket != turn) {

// Busy wait

}

// Critical section

turn = turn + 1;

Advantages of Hardware Solutions:

- Atomicity: These instructions guarantee atomic operations, meaning they can't be interrupted or corrupted by another process.

- Low Overhead: Hardware solutions often have lower overhead than higher-level software-based synchronization methods.

Disadvantages:

- Busy Waiting: Many hardware solutions involve busy waiting (e.g., test-and-set, spinlocks), which can waste CPU cycles.

- Starvation: Some processes may experience starvation if the critical section is frequently held by others.

- Not Fair: Hardware-based methods do not guarantee fairness, meaning some processes might get more access to the critical section than others.

Use in Modern Systems:

Most modern operating systems and programming languages use higher-level abstractions built on top of these hardware primitives, such as locks, semaphores, and monitors, to achieve mutual exclusion and prevent race conditions.

Strict Alternation

Strict Alternation is one of the simplest algorithms used to implement mutual exclusion between two processes. The idea behind strict alternation is that two processes (say, P1 and P2) will strictly alternate their execution of the critical section by using a shared variable that keeps track of whose turn it is to enter the critical section.

Working Mechanism

-

A shared variable

turnis introduced, which can hold either 0 or 1:turn = 0means it is P1's turn to enter the critical section.turn = 1means it is P2's turn to enter the critical section.

-

Before entering the critical section, each process checks whether it is its turn. If it's not, the process waits until the other process has finished its execution of the critical section and then proceeds.

int turn = 0; // Shared variable

void P1() {

while (true) {

// Entry Section

while (turn != 0) {

// Busy wait, waiting for turn

}

// Critical Section

// -- Critical section code for P1 --

// Exit Section

turn = 1; // Give turn to P2

// Remainder Section

// -- Remainder code for P1 --

}

}

void P2() {

while (true) {

// Entry Section

while (turn != 1) {

// Busy wait, waiting for turn

}

// Critical Section

// -- Critical section code for P2 --

// Exit Section

turn = 0; // Give turn to P1

// Remainder Section

// -- Remainder code for P2 --

}

}

Explanation:

-

Entry Section:

- Each process enters the critical section only when the shared variable

turnallows it to. For example, P1 will enter the critical section only ifturn == 0, and P2 will enter only ifturn == 1.

- Each process enters the critical section only when the shared variable

-

Critical Section:

- When a process is allowed to enter the critical section (after the entry section), it executes the critical section code.

-

Exit Section:

- After leaving the critical section, the process changes the value of

turnto give the other process the right to enter the critical section next.

- After leaving the critical section, the process changes the value of

-

Remainder Section:

- The code outside the critical section that the process can execute while waiting for its next turn.

Issues with Strict Alternation:

-

Busy Waiting:

- The processes continuously check the

turnvariable in a loop, which results in a busy-wait (spinning). This consumes CPU cycles unnecessarily.

- The processes continuously check the

-

No Progress Guarantee:

- If one process is delayed or halted before it enters its critical section, the other process must wait indefinitely for its turn to change. This is problematic for scenarios where one process may need to access the critical section more frequently than the other.

-

Not Suitable for Multiple Processes:

- Strict alternation is designed only for two processes. Extending this solution to multiple processes is inefficient and can lead to more complex synchronization problems.

-

Inefficiency:

- It forces the processes to alternate even if only one of them needs to access the critical section, which can cause unnecessary waiting.

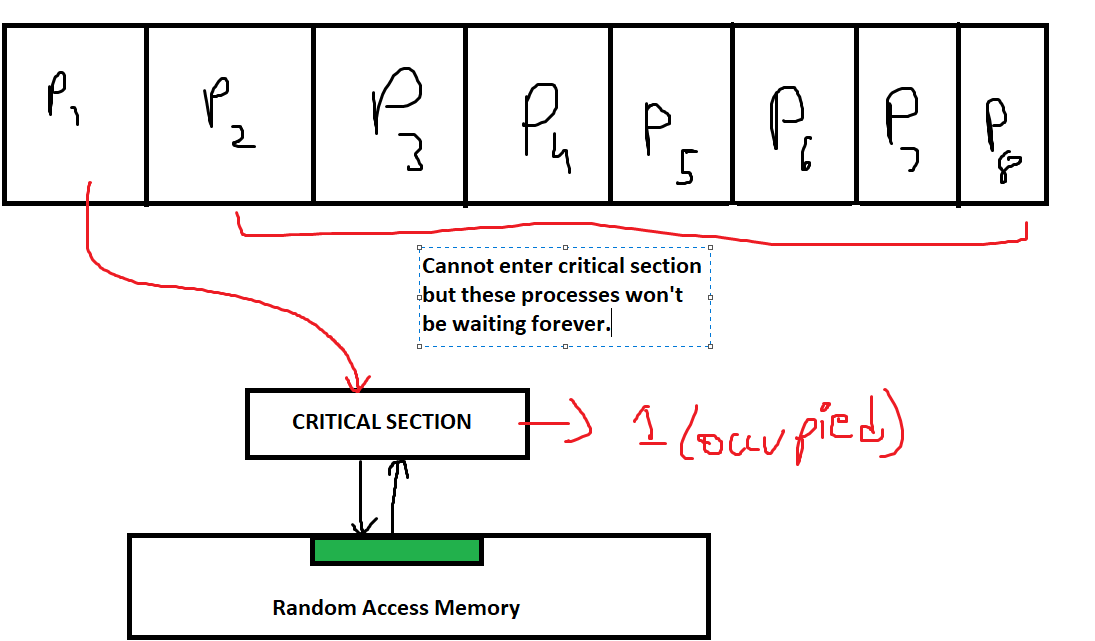

Peterson's Solution

Peterson’s Solution is a classic algorithm designed to solve the critical section problem for two processes, ensuring mutual exclusion, progress, and bounded waiting. It is a more efficient solution than Strict Alternation as it avoids unnecessary waiting and provides fairness between the processes.

Here we see process P1 occupying the critical section. The other processes are waiting in line to access the critical section as well.

Here's how Peterson's solution differs from Strict Alternation and the other hardware solutions: There is a check for progress within the critical section. If no progress is detected in the critical section (nothing is going on in the critical section) then the next process which requires access to the critical section will be granted access to it.

This ensures that the other processes are not waiting forever to enter the critical section.

Key Concepts in Peterson's Solution

- Mutual Exclusion: Only one process can be in the critical section at a time.

- Progress: If no process is in the critical section, the process that wishes to enter should be allowed to do so.

- Bounded Waiting: A process must not be forced to wait forever to enter the critical section.

Variables Used in Peterson's Solution

-

flag[]: An array of two boolean variables, one for each process, to indicate whether a process is ready to enter the critical section.

flag[0]: Process P1 wants to enter the critical section.flag[1]: Process P2 wants to enter the critical section.

-

turn: A shared variable used to indicate whose turn it is to enter the critical section.

turn = 0: It is P1's turn.turn = 1: It is P2's turn.

Working Mechanism

Each process follows these steps:

-

Entry Section:

- A process signals its intent to enter the critical section by setting its flag to

trueand giving the turn to the other process. - It then waits for the other process to either:

- Not want to enter the critical section (

flag[other] == false), or - If the other process also wants to enter, the process waits until it’s its own turn (

turn == my_turn).

- Not want to enter the critical section (

- A process signals its intent to enter the critical section by setting its flag to

-

Critical Section:

- The process enters the critical section once it satisfies the condition in the entry section.

-

Exit Section:

- After completing the critical section, the process sets its flag to

false, indicating that it no longer wishes to enter the critical section.

- After completing the critical section, the process sets its flag to

-

Remainder Section:

- The process executes code outside the critical section before potentially looping back to try entering again.

Example pseudocode:

boolean flag[2]; // Shared array to signal intention to enter critical section

int turn; // Shared variable to indicate whose turn it is

void P1() {

while (true) {

// Entry Section

flag[0] = true; // P1 signals intent to enter critical section

turn = 1; // Give turn to P2

while (flag[1] && turn == 1) {

// Busy wait until P2 is not interested or it is P1's turn

}

// Critical Section

// -- Critical section code for P1 --

// Exit Section

flag[0] = false; // P1 no longer needs the critical section

// Remainder Section

// -- Remainder code for P1 --

}

}

void P2() {

while (true) {

// Entry Section

flag[1] = true; // P2 signals intent to enter critical section

turn = 0; // Give turn to P1

while (flag[0] && turn == 0) {

// Busy wait until P1 is not interested or it is P2's turn

}

// Critical Section

// -- Critical section code for P2 --

// Exit Section

flag[1] = false; // P2 no longer needs the critical section

// Remainder Section

// -- Remainder code for P2 --

}

}

Explanation:

-

Entry Section:

- Each process sets its flag to

true, indicating it wants to enter the critical section. - The process then gives the

turnto the other process and waits until either:- The other process doesn't want to enter the critical section (

flag[other] == false), or - The

turnis in its favor (i.e., it becomes its turn).

- The other process doesn't want to enter the critical section (

- Each process sets its flag to

-

Critical Section:

- Once the conditions of the entry section are met, the process enters the critical section.

-

Exit Section:

- After completing its critical section, the process sets its flag to

false, meaning it no longer needs to be in the critical section.

- After completing its critical section, the process sets its flag to

-

Remainder Section:

- The process executes the remainder of its code and may later try to re-enter the critical section.

Example:

Let’s say P1 and P2 both want to enter the critical section simultaneously:

- P1 sets

flag[0] = trueand setsturn = 1. - P2 sets

flag[1] = trueand setsturn = 0.

Now:

- P1 will check the conditions

flag[1] && turn == 1to see if P2 also wants to enter and if it's P1’s turn. - P2 will check

flag[0] && turn == 0similarly.

Since P2 set the turn to P1's side last (turn = 0), P1 gets to enter the critical section first. P2 will wait until P1 completes its critical section.

Once P1 exits, it will set flag[0] = false. Now P2 can enter the critical section.

Advantages of Peterson’s Solution:

- Mutual Exclusion: Only one process can enter the critical section at a time.

- Progress: No process will be indefinitely delayed if it wishes to enter the critical section.

- Fairness: Both processes get a fair chance to enter the critical section.

- Simplicity: Peterson’s solution uses only two shared variables (a flag array and a turn variable).

Limitations:

- Busy Waiting: Just like Strict Alternation, Peterson's solution involves busy-waiting, which can be inefficient in real systems.

- Two Processes Only: Peterson’s solution is designed for only two processes. Extending it to more than two processes becomes increasingly complex.

So in the given diagram above, Peterson's solution will extend to only two processes at a time.

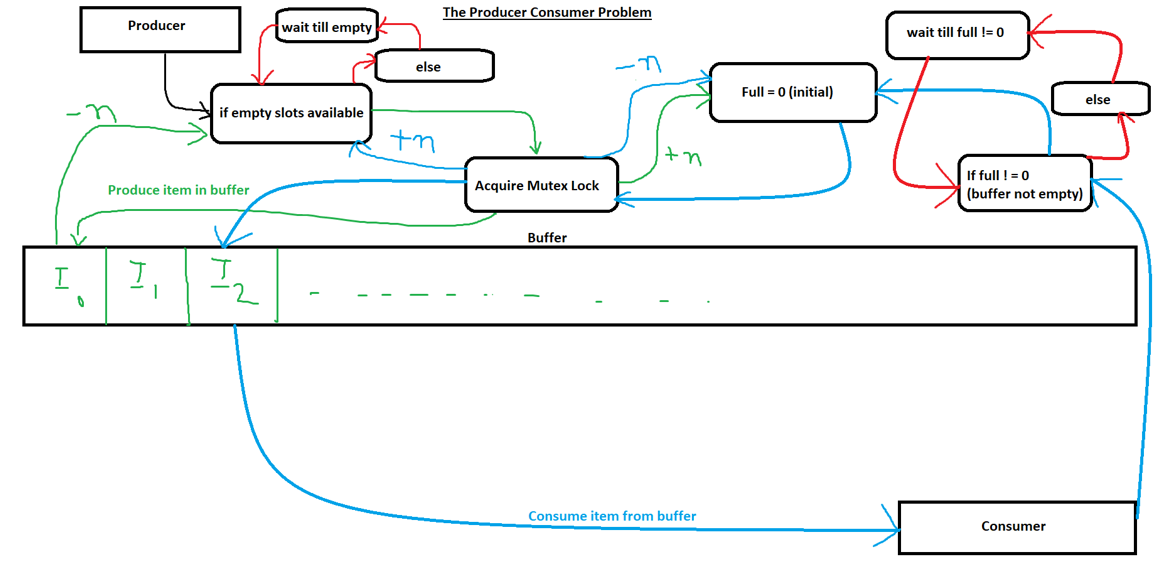

The Producer-Consumer Problem

The Producer-Consumer Problem is a classic synchronization problem that illustrates the challenge of coordinating processes that share a common resource, such as a buffer. In this problem, two types of processes interact:

- Producers: These processes generate data (or items) and place them in a buffer.

- Consumers: These processes consume (or remove) data from the buffer.

Problem Description:

- The producer produces items and places them in a shared buffer.

- The consumer consumes items from the buffer.

- If the buffer is full, the producer must wait until the consumer removes some items (i.e., the buffer has space).

- If the buffer is empty, the consumer must wait until the producer produces more items (i.e., the buffer has items).

The challenge is to ensure that both producers and consumers operate efficiently and correctly without interfering with each other, especially when the buffer is empty or full.

Shared Variables:

- Buffer: A shared space that holds items produced by the producer and consumed by the consumer. It has a limited capacity.

in: Points to the position where the producer will place the next item.out: Points to the position where the consumer will remove the next item.count: Tracks the current number of items in the buffer.

Key Issues:

- Mutual Exclusion: The buffer is a shared resource, so both the producer and the consumer must not access it simultaneously.

- Synchronization: Producers must wait when the buffer is full, and consumers must wait when the buffer is empty.

Solution Using Semaphores

The Producer-Consumer problem can be solved using semaphores, which are synchronization primitives that help control access to shared resources.

Three semaphores are commonly used:

empty: Counts the empty slots in the buffer (initially equal to the buffer size).full: Counts the number of filled slots in the buffer (initially 0).mutex: Ensures mutual exclusion when accessing the buffer (initialized to 1).

Explanation via Code

Shared Variables:

semaphore empty = buffer_size; // Initially, buffer is empty (all slots are available)

semaphore full = 0; // Initially, buffer is empty (no items)

semaphore mutex = 1; // For mutual exclusion

int buffer[buffer_size]; // Shared buffer

int in = 0; // Points to the next empty slot in the buffer (for producer)

int out = 0; // Points to the next item to be consumed (for consumer)

Producer:

void producer() {

int item;

while (true) {

item = produce_item(); // Produce an item (this could be any logic or function)

wait(empty); // Check if there is space in the buffer

wait(mutex); // Enter critical section (to access buffer)

buffer[in] = item; // Place the item in the buffer

in = (in + 1) % buffer_size; // Update 'in' to point to the next empty slot

signal(mutex); // Exit critical section

signal(full); // Signal that there is one more full slot

}

}

Consumer:

void consumer() {

int item;

while (true) {

wait(full); // Check if there is any item in the buffer

wait(mutex); // Enter critical section (to access buffer)

item = buffer[out]; // Consume the item from the buffer

out = (out + 1) % buffer_size; // Update 'out' to point to the next item

signal(mutex); // Exit critical section

signal(empty); // Signal that there is one more empty slot

consume_item(item); // Consume the item (this could be any logic or function)

}

}

Explanation of the Semaphores:

empty: This semaphore ensures that the producer waits if the buffer is full. It is initialized to the buffer size, and each time a producer inserts an item, it decrements the value ofempty. Ifemptybecomes 0, the producer waits until the consumer consumes an item.full: This semaphore ensures that the consumer waits if the buffer is empty. It is initialized to 0, and each time a producer inserts an item, it incrementsfull. Iffullbecomes 0, the consumer waits until the producer produces an item.mutex: This semaphore ensures mutual exclusion, preventing multiple producers or consumers from accessing the buffer at the same time.

Circular Buffer Mechanism:

The buffer is typically implemented as a circular buffer to handle the wrap-around behavior when the buffer's start and end points meet. The variables in and out are used to keep track of where the next item should be placed or removed. They are updated using a modulo operation to implement the circular nature of the buffer.

Key Properties of the Producer-Consumer Problem:

- Bounded Buffer: The buffer has a finite capacity, and both producers and consumers must be aware of this limit.

- Deadlock Prevention: The use of semaphores ensures that deadlock does not occur as long as proper signaling is followed.

- Starvation-Free: Both producers and consumers can continue working as long as the buffer has space (for producers) or items (for consumers), ensuring no process gets starved.

Challenges and Variations:

- Multiple Producers and Consumers: In real systems, there may be multiple producers and consumers. The logic remains similar, but care must be taken to ensure that the semaphores and buffer are shared properly among all processes.

- Unbounded Buffer: In some variations, the buffer size may be considered infinite, meaning that producers never have to wait. This is more of a theoretical abstraction.

Use Cases:

- I/O Buffers: In operating systems, producer-consumer problems are common in I/O systems, where data is produced by hardware or software and consumed by other parts of the system.

- Multithreading: In multithreaded applications, different threads can act as producers and consumers, exchanging data through shared memory.

- Message Queues: In message-passing systems, the producer-consumer pattern is implemented through queues where one process produces messages, and another consumes them.

Semaphores

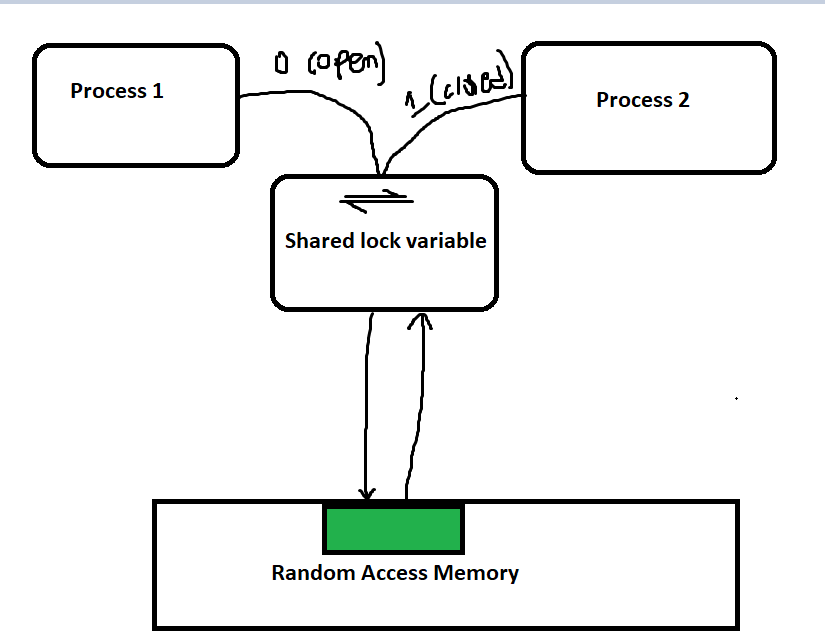

Semaphores are one of the most widely used mechanisms to handle synchronization and mutual exclusion in concurrent processes or threads. They are primarily used to control access to shared resources in a concurrent system, ensuring that no two processes can access a critical section simultaneously.

What is a Semaphore?

A semaphore is an abstract data type (or more specifically, a variable) used for signaling between processes. It can be considered a simple integer variable that can have one of two values: zero or a positive integer. The two basic operations that can be performed on a semaphore are:

-

Wait (P operation or down): This operation decreases the value of the semaphore by one. If the semaphore's value is already zero, the process performing the operation is blocked until the value becomes positive.

- If the semaphore is positive: It decrements the value.

- If the semaphore is zero: The process goes into a waiting state.

-

Signal (V operation or up): This operation increases the value of the semaphore by one. If there are any processes waiting on the semaphore, one of them is unblocked.

- If the semaphore is zero: It increments the value and allows one waiting process to proceed.

These operations are atomic, meaning that they are indivisible and cannot be interrupted in the middle of execution.

Types of Semaphores

Semaphores can be classified into two types:

-

Binary Semaphore:

- Also called mutexes.

- This type of semaphore has only two values: 0 and 1. It is used for ensuring mutual exclusion, i.e., ensuring that only one process can access the critical section at a time.

- Example: Locking a shared file for exclusive access by one process.

-

Counting Semaphore:

- This type of semaphore can take non-negative integer values. It is used for managing access to a resource with a limited number of instances.

- Example: Allowing multiple processes to access a fixed number of database connections (say 5 connections), where the counting semaphore would keep track of how many connections are available.

A diagram illustration of a binary semaphore.

Code explanation of semaphore operations

Wait (P operation):

wait(semaphore s) {

while (s <= 0); // Busy wait

s--;

}

- In the

waitoperation, if the semaphore value is greater than 0, the process can proceed and decrement the semaphore value. - If the semaphore value is 0 or less, the process waits until another process signals that the resource is available.

Signal (V operation):

signal(semaphore s) {

s++;

}

The signal operation increments the semaphore value and potentially unblocks any process waiting on the semaphore.

Above operations were of a counting semaphore.

Applications of Semaphores

Semaphores can be used in various synchronization problems, including:

-

Mutual Exclusion:

- Ensuring that only one process can enter its critical section at a time. A binary semaphore is typically used for this purpose.

-

Producer-Consumer Problem:

- Counting semaphores are used to keep track of empty and full slots in the buffer, and a binary semaphore ensures mutual exclusion when accessing the buffer.

-

Readers-Writers Problem:

- A counting semaphore is used to count the number of readers, and a binary semaphore is used to ensure that only one writer accesses the resource at a time.

-

Dining Philosophers Problem:

- Semaphores are used to control access to shared chopsticks (resources) to avoid deadlock and ensure that at most one philosopher can use a chopstick at a time.

Deadlock and Starvation

Semaphores can lead to two common problems:

-

Deadlock:

- A situation where two or more processes are waiting for each other to release resources, and none of them can proceed. This can occur if semaphores are not used carefully.

- Example: Two processes each hold one semaphore and wait for the other process to release the semaphore it is holding.

-

Starvation:

- A situation where some processes are never able to proceed because other processes are continuously favored. This can happen in priority-based semaphore systems, where higher-priority processes always get access to the resource before lower-priority processes.

Advantages of Semaphores

- Semaphores are simple and effective for controlling access to shared resources in concurrent systems.

- They allow processes to wait and signal each other, enabling coordination between processes or threads.

Disadvantages of Semaphores

- Busy Waiting: In a basic semaphore implementation, a process may enter a busy wait if the semaphore value is not favorable. This can waste CPU cycles. However, modern semaphore implementations avoid this with blocking mechanisms.

- Complexity: Semaphores can be tricky to use correctly, especially in large systems, and improper use can lead to issues like deadlock or starvation.

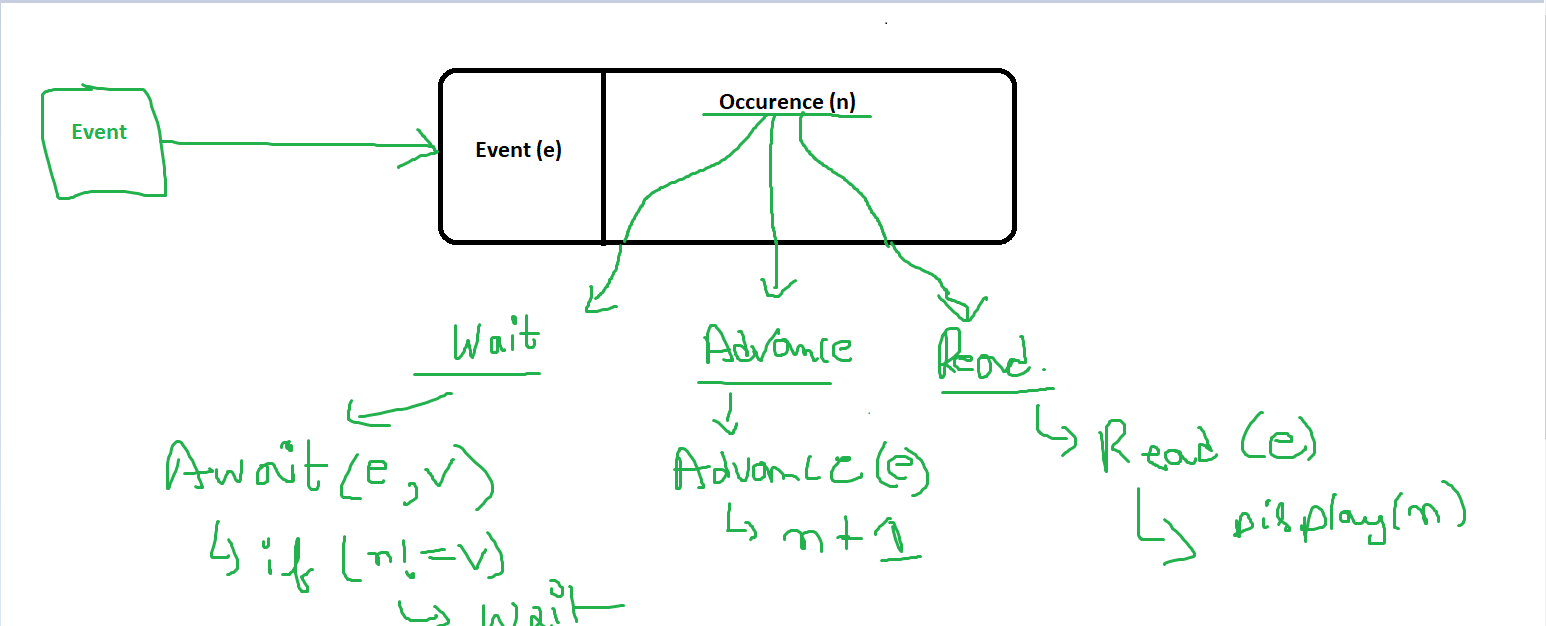

Event Counters

Event Counters are another synchronization primitive used in operating systems and concurrent programming to manage coordination between processes. They are primarily designed to handle situations involving multiple events or conditions that need to be synchronized, like signals or the completion of tasks.

Event counters address some of the limitations of semaphores, particularly issues related to the ordering of events in complex synchronization situations. They are specifically useful in producer-consumer problems or in managing complex dependencies between different operations.

Concept of Event Counters

An event counter is simply a non-negative integer variable that keeps track of the number of occurrences of a particular event. Operations on event counters involve waiting for a specific event to occur or advancing the counter once the event has occurred.

Event counters are typically associated with three main operations:

-

Wait Event (await):

- This operation causes a process to wait until the event counter reaches a specific value (or higher). The process is blocked until the desired event has occurred.

await(e, v): Waits until the event counterereaches or exceeds the valuev.

-

Advance Event (advance):

- This operation increments the event counter when an event occurs. It signals other processes that an event they are waiting for has happened.

advance(e): Increments the event countereby one and wakes up any processes waiting for the counter to reach the new value.

-

Read Event (read):

- This operation allows a process to read the current value of the event counter without modifying it.

read(e): Returns the current value of the event countere.

Operations on Event Counters

Await Operation

-

The

awaitoperation works similarly to a condition wait in condition variables. It blocks a process until the event counter reaches the specified value. -

Example:

await(e, v)causes the process to wait until the event counterebecomes equal to or greater thanv.

Advance Operation

-

The

advanceoperation increments the value of the event counter by 1, indicating that an event has occurred and that any waiting processes can check if their condition has been met. -

Example:

advance(e)increments the event countereby one, and if any processes are waiting for the counter to reach a certain value, they will be woken up.

Read Operation

-

The

readoperation simply returns the current value of the event counter without affecting its value. This can be used to check the status of an event without blocking or causing any changes. -

Example:

read(e)returns the current value of the event countere.

Example of Event Counters

Let’s consider an example where event counters are used to synchronize producer and consumer processes.

Producer-Consumer Problem:

- The producer is responsible for producing items and the consumer for consuming them. The event counter keeps track of how many items have been produced and consumed.

event_counter items_produced = 0;

event_counter items_consumed = 0;

void producer() {

while (true) {

produce_item();

advance(items_produced); // Notify that a new item has been produced

}

}

void consumer() {

while (true) {

await(items_produced, read(items_consumed) + 1); // Wait for the next item to be produced

consume_item();

advance(items_consumed); // Notify that an item has been consumed

}

}

In this example:

- Producer calls

advance(items_produced)every time it produces an item. - Consumer calls

await(items_produced, read(items_consumed) + 1)to wait for the next item to be produced before consuming it. - The two event counters

items_producedanditems_consumedare used to synchronize the two processes.

Advantages of Event Counters

- Ordered Synchronization: Event counters allow processes to wait for a specific event to occur in a well-defined order, providing more flexibility compared to semaphores.

- No Busy Waiting: Event counters eliminate the need for busy waiting, as processes can be put to sleep until the event counter reaches the desired value.

- Easier to Manage Dependencies: With event counters, managing dependencies between processes (e.g., waiting for multiple events to occur) is easier than using simple semaphores or locks.

- Greater Control: They provide finer control over synchronization than binary semaphores or mutexes, as processes can wait for a specific number of occurrences of an event.

Disadvantages of Event Counters

- Complexity: The use of event counters can make synchronization logic more complex, especially if there are many event counters and conditions to manage.

- Potential for Deadlock: Like semaphores, if event counters are not used properly, they can still lead to deadlock in certain situations (e.g., if processes are waiting for each other’s events indefinitely).

- Resource Usage: Event counters require additional memory and processing to manage the counter values and track the waiting processes.

Event Counters vs Semaphores

| Feature | Semaphores | Event Counters |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | For simple signaling and mutual exclusion | For managing events in a specific order |

| Blocking | Can block processes until the semaphore value changes | Blocks processes until the event counter reaches a specified value |

| Flexibility | Less flexible for ordered synchronization | More flexible for waiting for multiple occurrences of events |

| Read/Increment | No explicit read operation, typically used only with wait/signal | Can be read or incremented explicitly |

Monitors

Monitors are a high-level synchronization construct that provides a mechanism for safely allowing concurrent access to shared resources. They are designed to simplify the process of managing access to shared resources in multithreaded programs, preventing race conditions and ensuring that only one thread at a time can access the critical sections of code.

Unlike semaphores or locks, which require the programmer to manage synchronization explicitly, monitors encapsulate the synchronization logic, making it easier and less error-prone.

Monitors are especially useful in cases where the **simplicity of synchronization is more important** than fine-grained control over resource access.

Structure of a Monitor

A monitor is a module that contains:

- Shared Variables: These are the resources that need to be protected from concurrent access.

- Procedures/Methods: These are the operations that can be performed on the shared variables.

- Synchronization Mechanism: The monitor ensures that only one process or thread can execute a procedure at a time, preventing race conditions.

The structure can be visualized like this:

monitor MonitorName {

// Shared variables (e.g., resources)

var sharedVar1;

var sharedVar2;

// Procedures that operate on shared variables

procedure P1() {

// Code for P1

}

procedure P2() {

// Code for P2

}

// Other methods

}

The monitor guarantees mutual exclusion by allowing only one process or thread to execute any of its procedures at a time.

Monitor Operations

Here’s an example of how a monitor might be used to implement a producer-consumer problem:

monitor ProducerConsumer {

condition notEmpty;

condition notFull;

int buffer[BUFFER_SIZE];

int count = 0;

procedure produce(item) {

if (count == BUFFER_SIZE) {

wait(notFull); // Wait if buffer is full

}

buffer[count] = item;

count++;

signal(notEmpty); // Signal that buffer is not empty

}

procedure consume() {

if (count == 0) {

wait(notEmpty); // Wait if buffer is empty

}

item = buffer[--count];

signal(notFull); // Signal that buffer is not full

return item;

}

}

In this example:

- The producer process waits for the buffer to have space (using

wait(notFull)) and signals when it has added an item to the buffer (usingsignal(notEmpty)). - The consumer process waits for an item to be available (using

wait(notEmpty)) and signals when it consumes an item (usingsignal(notFull)).

This code ensures that producers and consumers are synchronized without race conditions.

Monitors vs Semaphores

| Feature | Monitors | Semaphores |

|---|---|---|

| Level of Abstraction | High-level synchronization primitive | Low-level synchronization primitive |

| Mutual Exclusion | Automatic mutual exclusion | Programmer must manually implement |

| Synchronization | Uses condition variables for waiting and signaling | Uses wait() and signal() |

| Ease of Use | Easier to use due to encapsulation and abstraction | Requires more careful handling by the programmer |

| Potential for Errors | Fewer errors due to built-in synchronization | More error-prone (e.g., deadlocks, race conditions) |

Advantages of Monitors

- Simplicity: Monitors encapsulate the synchronization logic, making them easier to use compared to semaphores and locks.

- Automatic Mutual Exclusion: The monitor ensures that only one process or thread can execute a monitor procedure at a time.

- Less Error-Prone: Because mutual exclusion is enforced automatically and condition variables provide a clear mechanism for waiting and signaling, monitors are less prone to race conditions and deadlocks than semaphores.

Disadvantages of Monitors

- Limited Flexibility: Monitors are less flexible than semaphores or locks. In some cases, fine-grained control over synchronization is needed, which monitors do not provide.

- Language Support: Monitors are not available in all programming languages. They are supported natively in some languages like Java, but in others, they must be implemented manually.

- Condition Variable Overhead: The use of condition variables can introduce overhead, particularly if many processes are waiting on the same condition.

Message Passing

Message passing is a method of communication used in distributed systems or between processes within the same system. It allows processes (or threads) to communicate with one another by sending and receiving messages, which is especially useful in systems where processes do not share memory. This approach is used both in inter-process communication (IPC) in operating systems and in distributed computing.

Key Concepts in Message Passing

- Processes: Independent units of execution that do not share memory but need to communicate.

- Messages: A structured data package (containing information such as a command, status, or data) sent from one process to another.

- Send/Receive Operations: The basic operations for message passing, where one process sends a message, and another process receives it.

How Message Passing Works

In message-passing systems, the sender process or thread uses a send operation to transmit data (the message) to a receiver process or thread. The communication is typically defined by three main operations:

- send(destination, message): Sends a message to the destination process.

- receive(source, message): Receives a message from the source process.

- message: The structured data exchanged between processes.

Message Passing Mechanisms

Message passing can be categorized based on different characteristics:

1. Direct vs Indirect Communication

- Direct Communication: Processes communicate by explicitly naming the recipient or sender of the message.

- Indirect Communication: Messages are sent to shared mailboxes or message queues, which decouple the sender from the receiver.

2. Synchronous vs Asynchronous Communication

- Synchronous Message Passing: The sender waits (or blocks) until the message is received by the recipient. This ensures that both processes synchronize at the point of communication.

- Asynchronous Message Passing: The sender does not wait for the recipient to receive the message. The message is stored in a buffer (message queue) until the recipient is ready to process it.

3. Blocking vs Non-blocking

- Blocking Send/Receive: The process is blocked (paused) until the operation (sending or receiving the message) is complete.

- Non-blocking Send/Receive: The process continues executing without waiting for the operation to complete. In non-blocking send, the message is buffered until it can be delivered; in non-blocking receive, the process checks for a message and moves on if none is available.

Direct vs Indirect Communication

-

Direct Communication:

-

Explicit Send and Receive: In direct communication, the sending and receiving processes must explicitly name each other. For example, process A sends a message to process B using

send(B, message), and process B receives the message usingreceive(A, message). -

Properties:

- Processes must know each other’s identity.

- There is a tight coupling between the sender and receiver

-

Example:

// Process A

send(B, message);

// Process B

receive(A, message);

- Indirect Communication:

-

Using Message Queues or Mailboxes: In indirect communication, messages are sent to a common storage location (called a mailbox or message queue), from which any process can retrieve messages. The sender and receiver are decoupled, meaning they don’t need to know each other’s identity.

-

Properties:

- Processes communicate via shared mailboxes.

- Greater flexibility and looser coupling between processes

Example:

// Process A

send(Mailbox, message);

// Process B

receive(Mailbox, message);

Synchronous vs Asynchronous Message Passing

-

Synchronous:

- In synchronous message passing, the sender and receiver synchronize at the point of communication.

- The sender must wait for the receiver to acknowledge that the message has been received.

- It ensures that both the sender and receiver are ready to communicate, which can be useful for ensuring that messages are delivered in order and that processes remain synchronized.

Example:

// Process A (Sender)

send(destination, message); // Blocks until the message is received

// Process B (Receiver)

receive(source, message); // Blocks until a message is available

Think of it as a satellite coming into the right orbital space at the right time to send data back to the receiver station on Earth, both the receiver and the satellite need to be synchronized at the exact time for the transfer to be successful.

- Asynchronous:

- In asynchronous message passing, the sender does not wait for the receiver to acknowledge receipt. Instead, the message is sent, and the sender continues its execution immediately.

- The message is usually stored in a buffer (a message queue) until the recipient process is ready to receive it.

- Asynchronous communication allows for more concurrency but can lead to challenges like buffer overflow or message ordering issues.

Think of it as a mailman dropping off your mail in your mailbox, the mailman won't wait for you to pick up the mail, it has other deliveries to do as well.

Example:

// Process A (Sender)

send(destination, message); // Non-blocking send

// Process B (Receiver)

receive(source, message); // Non-blocking receive

Blocking vs Non-blocking

-

Blocking Send/Receive:

- The process waits (blocks) until the message is sent or received.

- Blocking ensures that the sender knows when the message has been received, or the receiver knows when the message is available.

-

Non-blocking Send/Receive:

- The process does not wait; it continues execution after initiating the send or receive operation.

- Non-blocking operations are useful when a process needs to perform other tasks while waiting for a message.

Examples of Message Passing Systems

- MPI (Message Passing Interface): Used in parallel computing environments, MPI is a standard for message-passing between multiple processors in a distributed memory system. It supports both synchronous and asynchronous communication.

MPI example (C):

MPI_Send(&data, count, datatype, dest, tag, comm);

MPI_Recv(&data, count, datatype, source, tag, comm, &status);

- POSIX Message Queues: These are used in Unix-like operating systems (e.g., Linux) for inter-process communication. They allow processes to send and receive messages via a queue, ensuring ordered delivery.

POSIX Message Queue example:

mqd_t mqd = mq_open("/queue", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY, 0644, NULL);

mq_send(mqd, message, sizeof(message), 0);

mq_receive(mqd, buffer, sizeof(buffer), NULL);

- Actor Model (Erlang): The actor model is a conceptual model of message passing used in programming languages like Erlang. In this model, actors are independent entities that communicate via message passing, making it ideal for concurrent and distributed systems.

F.Y.I : Erlang is a language that was developed sometime near the 1980s for landline telephone companies to facilitate real time communication.

It's modern variant, Elixir is used a backend language in real-time chat applications like WhatsApp, Discord, Slack etc..

Erlang example:

receive

{sender, Message} ->

io:format("Received ~p~n", [Message]),

sender ! {self(), "Ack"};

after 5000 ->

io:format("Timeout~n")

end.

Advantages of Message Passing

- Simplifies Communication in Distributed Systems: Message passing is an effective way for processes on different machines (with no shared memory) to communicate.

- Loose Coupling: Processes can communicate without needing to know about the internal state or details of other processes.

- Modularity: Systems that use message passing are easier to develop and maintain since components (processes) are loosely connected.

- Supports Concurrency: Non-blocking message passing allows processes to run concurrently without waiting for messages.

Disadvantages of Message Passing

- Message Overhead: There can be significant overhead in creating, sending, and receiving messages, especially in distributed systems with large communication delays.

- Synchronization Issues: In asynchronous systems, it can be harder to ensure that messages are received in the correct order.

- Buffering: Asynchronous systems need buffer management for the messages, which may lead to issues like buffer overflow or message loss.

Readers-Writers Problem

The Readers-Writers Problem is a classical synchronization problem that deals with scenarios where a shared resource (such as a file or a database) is accessed by multiple processes, either to read from it or to write to it. The challenge is to ensure that:

- Multiple readers can access the shared resource simultaneously, since reading does not modify the resource.

- Only one writer can access the resource at a time, as writing modifies the resource, and allowing multiple writers (or a reader and a writer) simultaneously could result in data inconsistency or corruption.

Problem Statement

- Readers: Processes that read data from the shared resource.

- Writers: Processes that write data to the shared resource.

The goal is to design a synchronization mechanism to allow multiple readers to read concurrently but to ensure that writers have exclusive access.

Types of the Readers-Writers Problem

There are three major variations of the Readers-Writers Problem:

1. First Readers-Writers Problem (Reader Preference)

- Readers are given priority: This means that once a reader has started reading, no writer can start writing until all readers have finished. However, this can lead to writer starvation because readers may continuously access the resource, preventing writers from ever writing.

2. Second Readers-Writers Problem (Writer Preference)

- Writers are given priority: Writers are given access to the resource as soon as it becomes available, even if readers are waiting. This can prevent readers from accessing the resource for long periods, leading to reader starvation.

3. Third Readers-Writers Problem (No Preference)

- In this case, there is no strict preference for either readers or writers. Both readers and writers are treated equally, which prevents both starvation scenarios. This approach tries to balance fairness between readers and writers.

First Readers-Writers Problem (Reader Preference)

Problem: Readers are allowed to read concurrently, but writers must wait until all readers have finished.

Readers are given more priority than writers.

Conditions:

- Multiple readers can read the shared resource concurrently.

- If a writer requests access, it must wait until there are no readers accessing the resource.

Solution (Code)

We need the following:

- A shared counter to keep track of the number of readers.

- A mutex lock to synchronize access to the counter.

- A

writelockto ensure exclusive access for writers.

Variables:

read_count: Tracks how many readers are currently reading.mutex: Synchronizes access toread_count.writelock: Ensures that only one writer can write at a time.

// Reader process

while (true) {

wait(mutex); // Ensure mutual exclusion for read_count

read_count++; // Increment the number of readers

if (read_count == 1)

wait(writelock); // If it's the first reader, block writers

signal(mutex); // Release the mutex

// Critical Section (reading from the shared resource)

// Reader can read the resource here

wait(mutex); // Ensure mutual exclusion for read_count

read_count--; // Decrement the number of readers

if (read_count == 0)

signal(writelock); // If it's the last reader, allow writers

signal(mutex); // Release the mutex

}

// Writer process

while (true) {

wait(writelock); // Writer gets exclusive access

// Critical Section (writing to the shared resource)

// Writer can write to the resource here

signal(writelock); // Release the write lock

}

Step-by-Step Execution with Multiple Readers

1. First Reader Arrives

- The first reader calls

wait(mutex), locking access toread_count. - It increments

read_countfrom0to1. - Since

read_count == 1, this indicates that it is the first reader. The reader now callswait(writelock), which locks out any writers from the shared resource. - The mutex is then released with

signal(mutex), allowing other processes to accessread_count.

2. Additional Readers Arrive

- When subsequent readers arrive:

- They also call

wait(mutex)to lock access toread_count. - Each reader increments

read_count(e.g., from1to2,2to3, etc.). - However, only the first reader blocks writers by acquiring the

writelock. All subsequent readers just increment theread_countwithout affecting thewritelock.

- They also call

- Once a reader increments

read_count, it immediately releases the mutex withsignal(mutex), and enters the critical section to read the resource.

3. Critical Section (Reading)

- While in the critical section, multiple readers can read the resource concurrently.

- The

writelockis already acquired by the first reader, preventing writers from accessing the resource. - The readers don't need mutual exclusion among themselves because reading is a non-modifying operation, so multiple readers can read concurrently without interfering with each other.

- The

4. Readers Finish

- After a reader finishes reading, it must update the

read_count:- It calls

wait(mutex)again to lock access toread_count. - It decrements

read_countby 1.

- It calls

- If

read_countbecomes0(meaning it's the last reader), the reader releases thewritelockby callingsignal(writelock), allowing any waiting writers to access the resource. - Finally, the mutex is released with

signal(mutex)to allow other readers or writers to proceed.

Why Multiple Readers Can Read Concurrently

- The key reason multiple readers can read at the same time is that

writelockis only acquired by the first reader and is not re-acquired by subsequent readers. This allows any number of readers to incrementread_countand access the critical section simultaneously without blocking each other. - The

mutexensures that only one reader updatesread_countat a time, but it does not block access to the critical section, meaning that once a reader has entered the critical section, other readers can also enter.

Example with Multiple Readers

Let’s say we have 3 readers (R1, R2, R3) and 1 writer (W1):

-

R1 arrives:

read_count = 0→ R1 increments it to1.- Since

read_count == 1, R1 acquireswritelockto block the writer. - R1 enters the critical section.

-

R2 arrives:

read_count = 1→ R2 increments it to2.- R2 does not acquire the

writelockbecause it’s already locked by R1. - R2 enters the critical section to read concurrently with R1.

-

R3 arrives:

read_count = 2→ R3 increments it to3.- R3 also does not acquire the

writelock. - R3 enters the critical section, reading concurrently with R1 and R2.

-

R1 finishes:

read_count = 3→ R1 decrements it to2.- R1 does not release the

writelockbecause there are still active readers.

-

R2 and R3 finish:

- Each one decrements

read_count(2 → 1, then 1 → 0). - When

read_count == 0(after R3 finishes), R3 releases thewritelock, allowing any waiting writers to access the resource.

- Each one decrements

Second Readers-Writers Problem (Writer Preference)

Problem: Writers are given priority over readers to avoid writer starvation. This means when a writer is waiting to write, new readers are blocked from starting.

The key difference from the first Readers-Writers Problem is that this version gives priority to writers. If a writer is waiting, it should be given access to the shared resource as soon as possible, even if there are readers waiting.

Conditions:

- If a writer requests access, no new readers can start reading.

- Writers are given priority to ensure that they do not starve.

Solution (Code)

We add an additional variable to track whether a writer is waiting.

Variables:

read_count: Tracks the number of readers currently reading.write_count: Tracks whether a writer is waiting.mutex: Synchronizes access to bothread_countandwrite_count.writelock: Ensures exclusive access for writers.

// Reader process

while (true) {

wait(mutex); // Ensure mutual exclusion for read_count and write_count

while (write_count > 0) {

// Wait if there is a writer waiting

}

read_count++; // Increment the number of readers

if (read_count == 1)

wait(writelock); // First reader locks out writers

signal(mutex); // Release the mutex

// Critical Section (reading/writing from/to the shared resource)

wait(mutex); // Ensure mutual exclusion for read_count

read_count--; // Decrement the number of readers

if (read_count == 0)

signal(writelock); // Last reader allows writers

signal(mutex); // Release the mutex

}

// Writer process

while (true) {

wait(mutex); // Ensure mutual exclusion for write_count

write_count++; // Mark that a writer is waiting

signal(mutex); // Release the mutex

wait(writelock); // Writer gets exclusive access

// Critical Section (writing to the shared resource)

signal(writelock); // Release the write lock

wait(mutex); // Ensure mutual exclusion for write_count

write_count--; // Mark that the writer is done

signal(mutex); // Release the mutex

}

Step-by-Step explanation of the solution

Reader Process:

while (true) {

wait(mutex); // Ensure mutual exclusion for read_count and write_count

while (write_count > 0) {

// Wait if there is a writer waiting

}

read_count++; // Increment the number of readers

if (read_count == 1)

wait(writelock); // First reader locks out writers

signal(mutex); // Release the mutex

-

wait(mutex):- The first action in the reader process is to acquire the

mutexsemaphore. This ensures mutual exclusion when accessing or modifying theread_countandwrite_countvariables.

- The first action in the reader process is to acquire the

-

while (write_count > 0):- Before readers can access the shared resource, they check if there are any writers waiting. If

write_count > 0, it means there are writers waiting for access, so the reader waits here until there are no more writers.

- Before readers can access the shared resource, they check if there are any writers waiting. If

-

read_count++:- Once the reader knows no writer is waiting, it increments

read_count, which tracks the number of readers currently accessing the resource.

- Once the reader knows no writer is waiting, it increments

-

if (read_count == 1):- If the reader is the first reader (i.e.,

read_count == 1), it locks out writers by acquiring thewritelock. This prevents writers from accessing the resource while readers are active.

- If the reader is the first reader (i.e.,

-

signal(mutex):- The reader releases the

mutex, allowing other processes (either readers or writers) to accessread_countandwrite_count.

- The reader releases the

Critical Section:

- The reader now enters the critical section and performs its reading operation. Multiple readers can access this section simultaneously, as long as no writer is active.

// Critical Section (reading/writing from/to the shared resource)

After Critical Section

wait(mutex); // Ensure mutual exclusion for read_count

read_count--; // Decrement the number of readers

if (read_count == 0)

signal(writelock); // Last reader allows writers

signal(mutex); // Release the mutex

}

-

wait(mutex):- After finishing its read operation, the reader once again acquires the

mutexto safely decrementread_count.

- After finishing its read operation, the reader once again acquires the

-

read_count--:- The reader decrements

read_countto indicate that one fewer reader is active.

- The reader decrements

-

if (read_count == 0):- If this reader is the last reader (i.e.,

read_count == 0), it releases thewritelock, allowing writers to proceed.

- If this reader is the last reader (i.e.,

-

signal(mutex):- The reader releases the

mutexsemaphore, completing its operation.

- The reader releases the

Writer Process:

while (true) {

wait(mutex); // Ensure mutual exclusion for write_count

write_count++; // Mark that a writer is waiting

signal(mutex); // Release the mutex

-

wait(mutex):- The writer starts by acquiring the

mutexto safely update thewrite_count.

- The writer starts by acquiring the

-

write_count++:- The writer increments

write_count, indicating that a writer is waiting to access the shared resource.

- The writer increments

-

signal(mutex):- The writer releases the

mutex, allowing other processes to accessread_countandwrite_count.

- The writer releases the

wait(writelock); // Writer gets exclusive access

// Critical Section (writing to the shared resource)

signal(writelock); // Release the write lock

-

wait(writelock):- The writer then acquires the

writelock, ensuring that it has exclusive access to the shared resource. No readers or other writers can access the resource while the writer is active.

- The writer then acquires the

-

Critical Section:

- The writer performs its writing operation in the critical section. Only one writer can access this section at a time.

// Critical Section (reading/writing from/to the shared resource)

-

signal(writelock):- After finishing its writing operation, the writer releases the

writelock, allowing other readers or writers to proceed.

- After finishing its writing operation, the writer releases the

wait(mutex); // Ensure mutual exclusion for write_count

write_count--; // Mark that the writer is done

signal(mutex); // Release the mutex

}

-

wait(mutex):- The writer once again acquires the

mutexto safely decrementwrite_count.

- The writer once again acquires the

-

write_count--:- The writer decrements

write_count, indicating that one fewer writer is waiting or writing.

- The writer decrements

-

signal(mutex):- Finally, the writer releases the

mutex, completing its operation.

- Finally, the writer releases the

Key Points in the Code:

-

Writers' Priority: In this second variant of the Readers-Writers Problem, writers have priority over readers. Readers check

write_countbefore accessing the shared resource. If a writer is waiting, readers are blocked until the writer has finished. -

read_countandwrite_count:read_counttracks the number of active readers. If the first reader arrives, it locks out writers by acquiring thewritelock, and the last reader releases the lock when done.write_counttracks the number of waiting writers. If a writer arrives, it blocks further readers until the writer is finished.

-

Semaphores:

mutexensures mutual exclusion when modifyingread_countandwrite_count.writelockis used to give exclusive access to writers when needed, preventing readers from entering the critical section.

Third Readers-Writers Problem (No Preference)

This variation aims to prevent both reader and writer starvation by balancing access between readers and writers. It allows both readers and writers to access the shared resource fairly without giving preference to either.

Solution:

To avoid starvation, readers and writers are treated fairly by alternating their access to the resource. Implementing this requires additional logic to ensure that neither side gets preference. The solution can be complex, often involving priority queues or other fairness mechanisms.

Key Features:

- No priority is given to either readers or writers.

- The solution ensures that no process (reader or writer) gets starved, meaning neither group can be indefinitely postponed from accessing the shared resource.

Code Example for the No Preference Variant:

// Semaphores

semaphore mutex = 1; // Ensures mutual exclusion for read_count and write_count

semaphore writelock = 1; // Provides exclusive access to writers

semaphore queue = 1; // Used to ensure no process starves (reader or writer)

// Shared Counters

int read_count = 0; // Keeps track of the number of active readers

int write_count = 0; // Keeps track of the number of active writers

// Reader process

while (true) {

wait(queue); // Ensure that readers and writers are queued fairly

wait(mutex); // Ensure mutual exclusion for read_count

read_count++; // Increment the number of readers

if (read_count == 1)

wait(writelock); // First reader locks out writers

signal(mutex); // Release mutex

signal(queue); // Allow other processes to proceed

// Critical Section (reading from the shared resource)

wait(mutex); // Ensure mutual exclusion for read_count

read_count--; // Decrement the number of readers

if (read_count == 0)

signal(writelock); // Last reader allows writers

signal(mutex); // Release mutex

}

// Writer process

while (true) {

wait(queue); // Ensure that readers and writers are queued fairly

wait(writelock); // Writer gets exclusive access

signal(queue); // Allow other processes to proceed

// Critical Section (writing to the shared resource)

signal(writelock); // Release the write lock after writing is complete

}

Explanation:

Reader Process:

-

wait(queue):- When a reader process wants to access the shared resource, it first waits for the