Module 4 -- Quantum Mechanics

Index

- Black body radiation

- The Photo-electric effect

- The Compton Effect

- The De Broglie Hypothesis

- Heisenberg's uncertainty principle

- Schrodinger Wave Equation

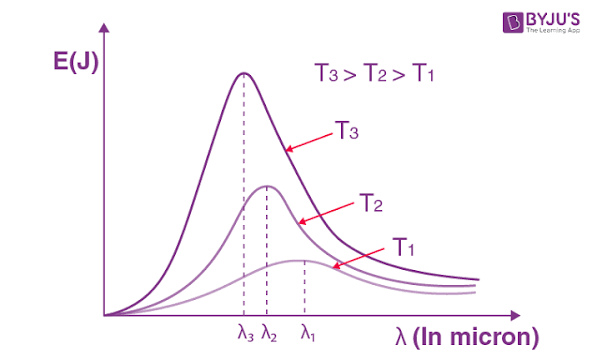

Black body radiation

Black body radiation is the electromagnetic radiation emitted by a theoretical object that absorbs all incident radiation and, at thermal equilibrium, emits radiation dependent only on its temperature.

What is a black body?

-

A black body is an idealized object that absorbs all electromagnetic radiation incident upon it, with no reflection or transmission.

-

While no real object is a perfect black body, an opening in a hollow enclosure is a good approximation, as is a furnace or the sun.

Explaining the black body radiation using the photon concept.

The Problem

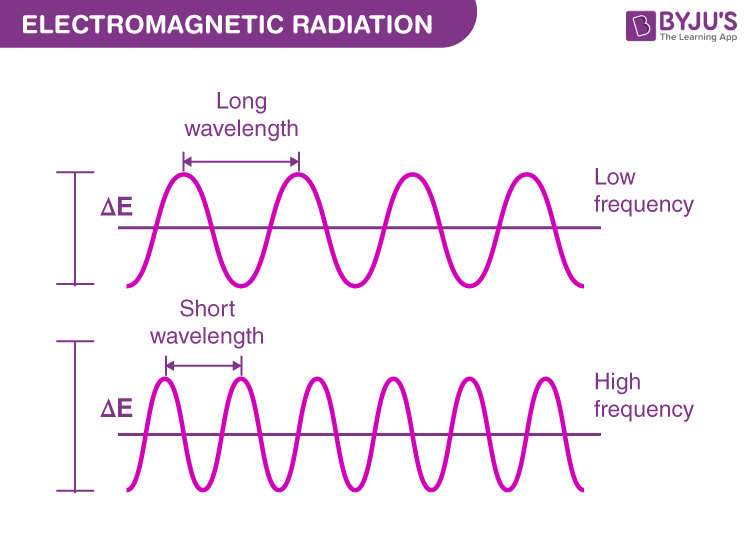

Classical physics (specifically the Rayleigh-Jeans law) assumed that energy was continuous and that vibrating charged particles within a heated object could have any energy value. This led to a formula that accurately described radiation at long wavelengths but predicted that an infinite amount of energy would be emitted at high frequencies (short wavelengths), a clear contradiction of experimental results known as the ultraviolet catastrophe.

Quantum Explanation: The Photon Concept

Max Planck resolved this paradox in 1900 by proposing a radical hypothesis that laid the foundation for quantum mechanics:

-

Energy Quantization: Planck suggested that energy exchange between the walls of a black body cavity and the electromagnetic radiation (photons) could only occur in discrete amounts, or quanta.

-

Photon Energy: The energy (

) of a single quantum(photon) is directly proportional to it's frequency , as defined by the equation:

where

- Discrete Energy Levels: The vibrating oscillators (atoms/electrons) in the black body walls can only exist in specific, equally spaced energy states (e.g.

, , etc.) They absorb energy to jump to a higher state or emit a photon to drop to a lower state. (same concept behind a 3-phase, 4-phase LASER where the electrons gain more energy on jumping to a higher state and emit photons when dropping to a lower state.)

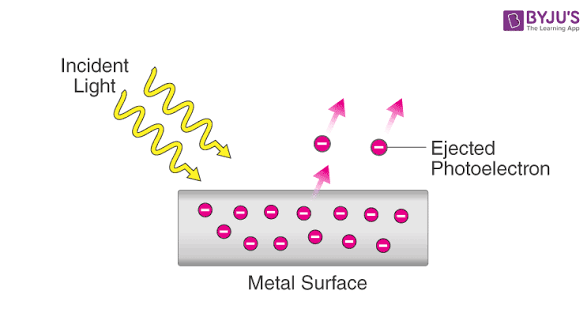

The Photo-electric effect

The photoelectric effect is the phenomenon where electrons, called photoelectrons, are emitted from a material's surface when light shines on it. This effect provides key evidence for the particle nature of light (photons) and was successfully explained by Albert Einstein using Max Planck's quantum theory, earning Einstein the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921.

Classical Physics vs. Experimental Results

Before Einstein's explanation, classical wave theory predicted that a brighter light (higher intensity) should result in higher-energy electrons, and any frequency of light should eventually cause emission if the intensity was high enough or given enough time. However, experiments revealed:

-

Electron emission only occurred if the light's frequency was above a certain minimum (threshold frequency).

-

The kinetic energy of the emitted electrons depended only on the light's frequency, not its intensity.

-

Emission was instantaneous, with no time delay for even very dim light, as long as the frequency condition was met

Einstein's Explanation: The Photon Concept

Einstein's theory reconciled these observations by extending Planck's idea that light energy comes in discrete packets (photons). The explanation is based on a one-to-one collision between a single photon and a single electron:

-

Energy Transfer: When a photon strikes the metal surface, it transfers all of it's energy (

) to a single electron. -

Work Function (

): A portion of this energy is used by the electron to overcome the attractive forces that bind it to the metal's surface, known as the work function. -

Kinetic Energy: The remaining energy is converted into the kinetic energy of the ejected electron.

The Photoelectric Equation

Einstein's photoelectric equation mathematically describes this interaction:

or:

where:

is Planck's constant (approximately ). is the frequency of incident light. is the work function of the specific metal. is the maximum kinetic energy of the emitted photoelectron.

The Compton Effect

The Compton effect (or Compton scattering) is the phenomenon where a high-energy photon, typically an X-ray or gamma ray, collides with a free or loosely bound electron, resulting in a decrease in the photon's energy and an increase in its wavelength.

This effect cannot be explained by classical wave theory, which predicts that the scattered radiation should have the same wavelength as the incident radiation. In 1923, Arthur Compton explained the effect by applying the photon concept and treating the interaction as a collision between two particles: a photon and an electron.

Explanation using the Photon Concept

The explanation of the Compton effect relies on two fundamental principles: the conservation of energy and the conservation of momentum.

-

Photon as a Particle with Momentum: Unlike classical waves, photons are treated as discrete packets of energy that also possess momentum. The momentum (

) of a photon is related to its wavelength ( ) by the equation where is Planck's constant. -

The Collision: When an incident photon collides with an electron (assumed to be at rest or loosely bound), it behaves like a cue ball hitting another ball. The photon transfers a portion of its energy and momentum to the electron.

-

Energy Transfer and Wavelength Shift: Because the incident photon gives away some of its energy to the recoiling electron, the scattered photon has less energy. According to the energy-frequency relationship (

),

lower energy corresponds to a lower frequency and, consequently, a longer wavelength. -

Conservation Laws: Compton used relativistic mechanics to analyze the collision, applying the conservation of both energy and momentum (which is a vector quantity, accounting for direction) to derive a formula that accurately predicts the change in wavelength based on the angle at which the photon is scattered.

The Compton Shift Formula

The change in wavelength (

or:

The term

Constants to remember:

(Planck's constant) (speed of light) (mass of the electron) (or ) (in angstroms) (important) is the scattering angle of the photon (will be given). (for energy related calculations) (for energy related calculations)

Practice Numericals for the Compton Effect

Numerical 1: Calculating scattered wavelength and the electron kinetic energy

An X-ray photon with an initial wavelength of

- The wavelength of the scattered photon

- The kinetic energy

imparted to the recoiling electron.

Constants:

- Planck's constant:

- Speed of light:

(mass of the electron)

(a) The wavelength of the scattered photon

Firstly the Compton shift:

Next,

So,

(b) The Kinetic Energy imparted to the electron will be:

This is because in cases like the Compton effect during collision, the amount of energy lost by the photon is the exact amount of energy the electron gains to get scattered. The energy is conserved.

Thus,

Practice Problem: The Backward Scattering

A beam of X-ray photons with a wavelength of

Calculate:

- The scattering angle (

): Through what angle were the photons deflected? - The Kinetic Energy (

) of the electron: How much energy did the electron carry away (in Joules)?

Constants for your calculation:

(Compton Wavelength)

1. Scattering Angle

We know that the Compton Shift is given by:

or:

Rounding off for simplicity:

This means that the collision is head on.

2. The Kinetic Energy of the scattered electron.

The scattered electron's energy comes directly from the energy difference between the photon before it struck the electron and the photon after it struck the electron.

In this case, since the collision is head-on, the

Given:

So,

The De Broglie Hypothesis

The De Broglie hypothesis, proposed by French physicist Louis De Broglie in 1924, is a fundamental tenet of quantum mechanics stating that all matter exhibits wave-particle duality. While classical physics treats matter solely as particles, this hypothesis suggests that moving particles also possess wave-like characteristics.

Core Principles

-

Matter Waves: Every moving material particle (such as an electron or a proton) has an associated wave, often referred to as a matter wave or de Broglie wave.

-

Symmetry of Nature: De Broglie’s reasoning was partially based on the idea that if light—traditionally viewed as a wave—could behave like a particle (photon), then nature’s inherent symmetry suggests particles should also behave like waves.

The De Broglie Equation

The hypothesis relates a particle's wavelength

where:

(Planck's Constant) (Speed of light) is the mass of the particle is the velocity of the particle

Key Implications

-

Microscopic vs. Macroscopic: The wave nature is only significant for subatomic particles with very small mass. For macroscopic objects (like a moving ball), the mass is so large that the wavelength becomes infinitesimally small and undetectable.

-

Bohr's Atomic Model: De Broglie's hypothesis provided a theoretical basis for Bohr's model of the atom. It explained that electrons inhabit specific orbits because only certain circumferences allow the electron's matter wave to form a standing wave, preventing energy loss through radiation.

-

Experimental Proof: The hypothesis was confirmed in 1927 by the Davisson-Germer experiment, which demonstrated that electrons could be diffracted—a property unique to waves—when fired at a nickel crystal.

Difference from Electromagnetic Waves

Unlike light or radio waves, matter waves are not electromagnetic. They do not consist of oscillating electric and magnetic fields and cannot propagate through a vacuum without the physical presence of the particle itself.

Practice Problem 1: The Macroscopic World

Calculate the de Broglie wavelength of a baseball with a mass of

- Constants:

- Goal: See just how small the wavelength is for everyday objects.

Given:

The de Broglie wavelength for this:

Practice Problem 2: The Microscopic World

Calculate the de Broglie wavelength of an electron (

- Goal: Compare this wavelength to the size of an atom (

).

Given:

The de Broglie wavelength for this:

The Energy-Wavelength Relation

In many lab experiments (like Electron Microscopy), you don't know the velocity (

We can combine the classical Kinetic Energy formula with de Broglie’s:

- Rearranging for momentum (

), we get: - Substituting this into

:

Example

An electron (

Calculate its de Broglie wavelength.

Given:

- Mass of electron:

- Kinetic Energy of the accelerated electron:

The de Broglie wavelength of the accelerated electron:

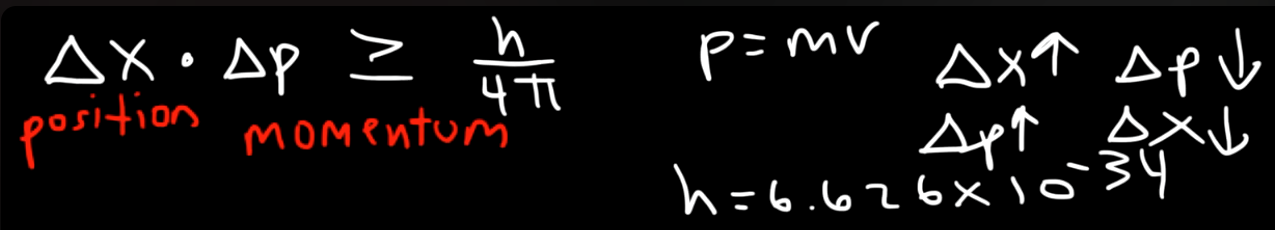

Heisenberg's uncertainty principle

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BNYz5EKXVeI

Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle, given by Werner Heisenberg in 1927, this principle only works on the microscopic scale, on the subatomic level. It states that, it is impossible to simultaneously measure certain pairs of physical properties, such as **position (

The principle reveals that at the subatomic level, the more accurately you determine a particle's position, the less accurately you can know its momentum, and vice versa.

Key Concepts

-

Wave-Particle Duality: The principle arises because quantum objects (like electrons) behave like waves. A perfectly localized wave has an indeterminate wavelength (momentum), while a wave with a precise wavelength is spread out over space.

-

Intrinsic Limit: This uncertainty is not due to clumsy measurement tools or experimental error; it is an inherent property of nature.

Practice Problem 1

1 > (a):

Given:

- Velocity of electron

: - Mass of electron is

The uncertainty in the momentum of the electron is:

The uncertainty in the position of the electron is:

or: (removing the inequality for solving purposes)

1> (b):

Given mass of ball:

Given uncertainty value of velocity of the ball:

The uncertainty in the momentum is given by:

The uncertainty in the position of the electron is given by:

(Removing the inequality for simplification purposes)

Schrodinger Wave Equation

The Concept

Think of it this way: In classical physics, we use Newton’s Second Law (

The Schrödinger equation is the "law of motion" for this wavefunction. It doesn't tell you exactly where the particle is; it tells you how the probability wave of that particle evolves over time and space.

The Equation (Time-Independent)

For a particle moving in one dimension, the most common form of the equation is:

Breaking down the terms:

-

(The Wavefunction): Contains all the information about the particle. -

(Kinetic Energy): This part represents the energy of the particle's motion. The is a derivative that measures how much the wave "curves." -

(Potential Energy): This represents the environment (like an electric field or a "box") pushing on the particle. -

(Total Energy): is the total energy of the system. -

(Reduced Planck's Constant): Defined as .

Why is this equation so important?

-

Quantization: It explains why electrons only live in specific energy levels.9 The math only "works" for certain values of

—much like a guitar string only vibrates at specific notes. -

Probability Density: While

can be a complex number, its square, , tells you the probability of finding the particle at a specific spot. -

The End of Certainty: It officially replaces the idea of "orbits" with "orbitals" (clouds of probability).

Detailed Explanation

1. What is the "Wave"?

When we talk about the wave in the Schrödinger equation, it is not a physical wave emitted by the electron (like a radio wave coming off an antenna). Instead:

-

The electron is the wave.

-

It is a mathematical wave of "possibility."

-

This is the heart of wave-particle duality: In transit, the electron acts like a spread-out wave (it can interfere with itself, go through two slits at once, etc.). But when you look at it, the wave "collapses," and you find a particle at a specific point.

2. Probability vs. Path

Earlier, I was confused, if the equation gives the probability of a "path." In quantum mechanics, the idea of a "path" (like a ball flying through the air) actually disappears. Instead, the Schrödinger equation gives you the probability of finding the particle at a specific point at a specific time (on being observed).

3. How it relates to Heisenberg

-

Heisenberg tells you the limit: "You cannot sharpen your focus on position and momentum at the same time."

-

Schrödinger gives you the map: It tells you the precise probability for every single point in space.

If Heisenberg says the electron is somewhere in a range of 1 nanometer, Schrödinger’s equation will tell you, "There is a 10% chance it's at the left edge, a 50% chance it's in the middle, and a 5% chance it's already tunneled slightly outside the wall."

The Schrödinger Equation: A Visual Breakdown

Think of the wavefunction

The equation explains how that cloud moves:

- Kinetic Energy term: Tells us how the cloud spreads out or "wiggles." (Fast electrons have more "wiggles" or higher frequency).

- Potential Energy term: Tells us how the environment (like a nucleus) pulls on or traps the cloud.

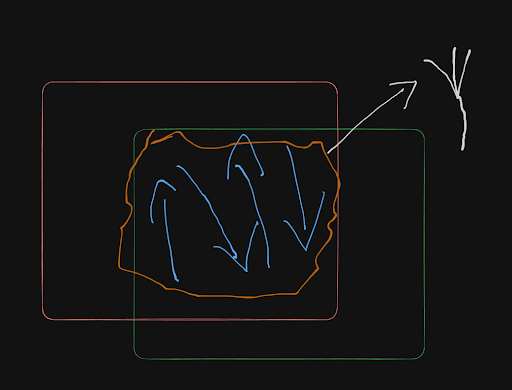

The "Particle in a Box" thought experiment.

Imagine an electron trapped between two invisible walls.

Imagine that the electron is denoted by the blue arrows and that it is moving back and forth by crashing against the orange and the green walls.

The orange "cloud of probabilities" is the wavefunction

The moment an observer observes the electron, only the does the cloud of probabilities collapse and the electron instantly collapses to a specific position, with the probability as given by Schrodinger's Equation.

The way we can know the velocity of the electron is because in this model, the Infinite Square Well model, when unobserved, this cloud of probabilities is actually a wave. (Coming from the wave-particle duality, that until observed the electron is a wave and once observed it collapses to a particle.)

So, when we compress the free area available to the electron by pushing the walls closer, we reduce the wavelength of the electron, causing it to have a higher frequency, thus achieving more momentum, and thus more Kinetic Energy.

(Since wavelength is inversely related to frequency in any consistent medium).

As:

The speed of a wave